print, etching, architecture

# print

#

etching

#

holy-places

#

charcoal drawing

#

form

#

romanesque

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

arch

#

line

#

cityscape

#

charcoal

#

architecture

Copyright: Public domain

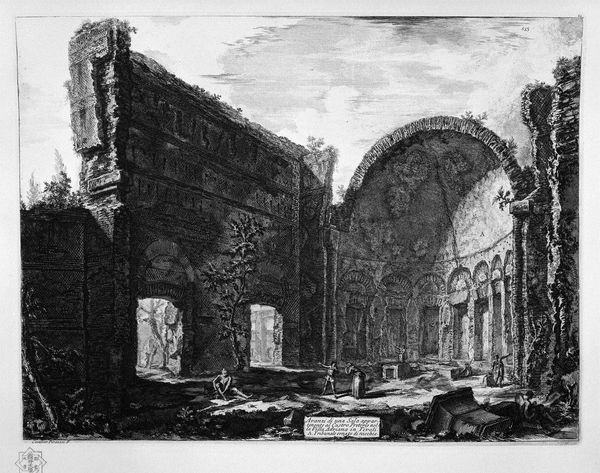

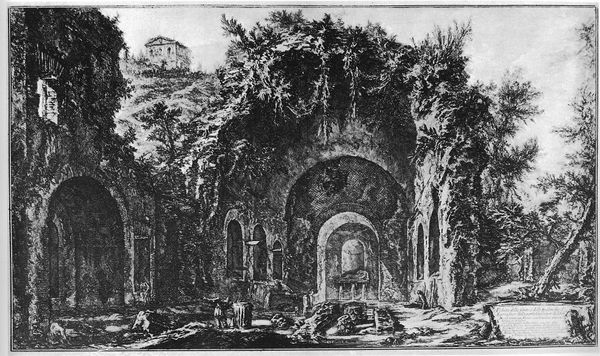

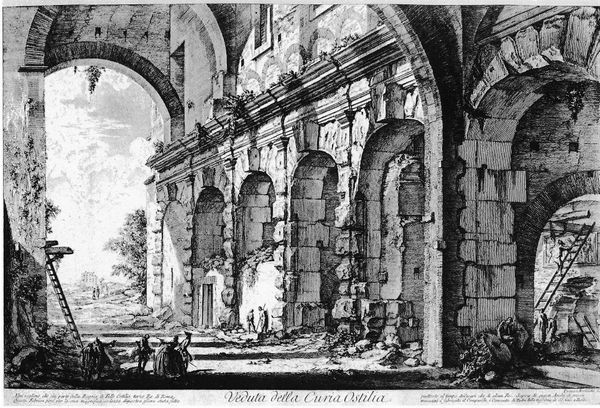

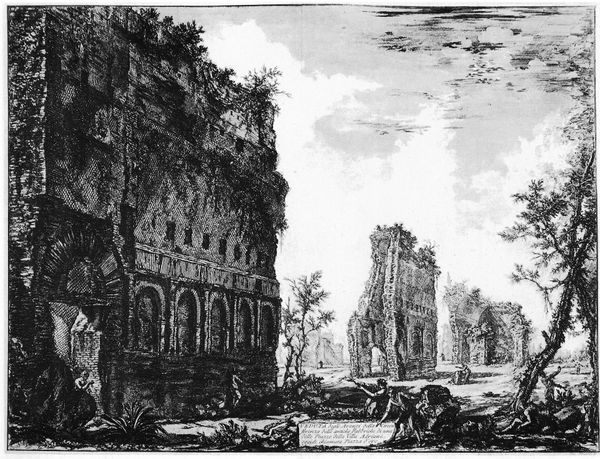

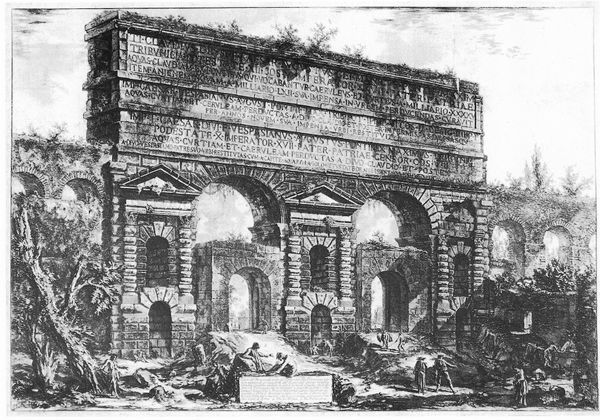

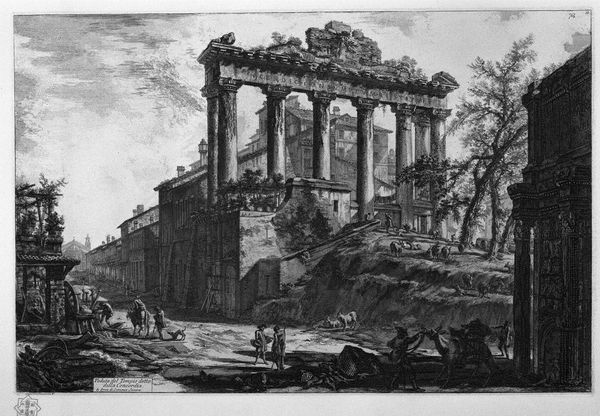

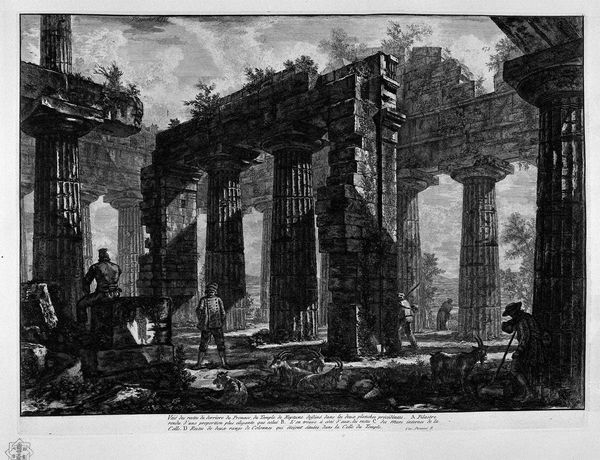

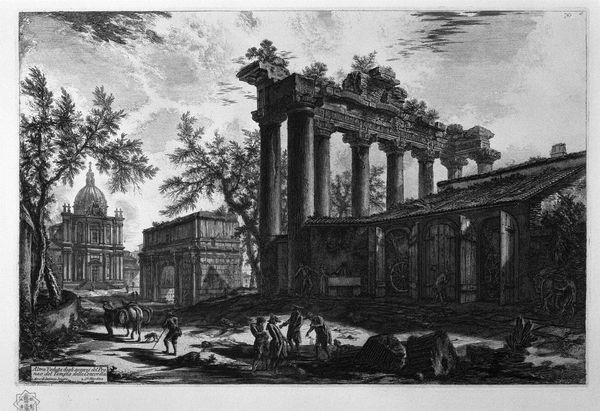

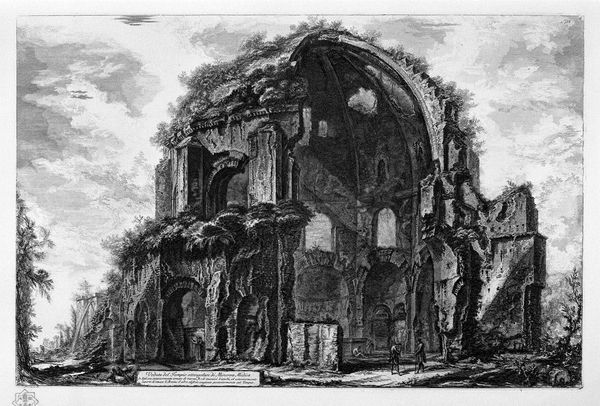

Editor: Here we have "Commonly called the Temple of Janus," an etching by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The stark contrast between light and shadow really jumps out, giving this imagined cityscape a dramatic feel. What stands out to you? Curator: It's a compelling image, isn't it? Piranesi wasn't just documenting ancient ruins, he was actively shaping a vision of Rome. This print reveals how architectural imagery becomes a potent tool for constructing a historical narrative. What do you notice about the figures included in the image? Editor: They seem almost dwarfed by the ruins. Like observers or wanderers amidst a lost grandeur. Curator: Precisely! They are consciously placed. Piranesi deliberately emphasizes the scale and imposing presence of the Roman past, positioning contemporary society in relation to this perceived golden age. In a sense, he critiques his present by glorifying the past. What message does this convey to his 18th-century audience? Editor: That the present is in decline compared to the achievements of antiquity? A call to revive those virtues, perhaps? Curator: Exactly. The choice to depict the temple overgrown and crumbling isn't accidental. Consider who were the consumers of these prints. It served the burgeoning Grand Tour, catering to wealthy Europeans seeking tangible connections to antiquity and feeding into complex social hierarchies and imperial ambitions. It raises questions about the ownership of history itself. Editor: So, Piranesi wasn’t just showing us Rome, but also telling us how to think about Rome, and, by extension, about power. That's fascinating. Curator: Indeed. These prints are not neutral records, but carefully constructed arguments about cultural and political power, masked within the seemingly objective depiction of ruins. Editor: I never thought about historical imagery this way. Now I realize there’s much more beneath the surface than just a pretty picture. Curator: And that is the essence of art history—understanding how art interacts with its world, then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.