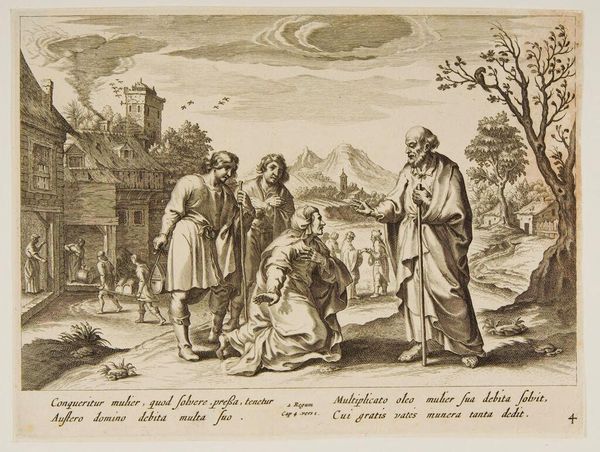

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 449 mm, width 340 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This print, "Terugkeer naar Jeruzalem," by Adriaen Lommelin, made sometime between 1630 and 1677, depicts Mary and Joseph returning to Jerusalem. It's striking how detailed the city is rendered in contrast to the more generalized landscape. What strikes you most about it? Curator: What fascinates me is the printmaking process itself. Think about the labor involved in creating those intricate lines on the copper plate. It wasn’t just artistic skill, but a physical, repetitive act, mirroring the repetitive nature of other early modern trades. Do you see any connections between the materiality of the print and the story being told? Editor: Well, the precision of the lines does lend a sense of order to the narrative, perhaps reflecting the strictures of religious doctrine in that era. But the act of mass production, facilitated by the print medium, also feels relevant. Were prints like this widely circulated, becoming a form of religious propaganda? Curator: Exactly! And consider the market for these prints. Who was consuming them? Were they affordable for the working class? The engraving democratized the image, making religious narratives accessible beyond the elite, while simultaneously solidifying those narratives through repetition and widespread consumption. It raises interesting questions about art's role in shaping belief. Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn't fully considered. It's easy to get lost in the image itself, but thinking about the means of production opens up a whole new layer of interpretation about the social and economic forces at play. Curator: Indeed. Examining the materials and processes reveals the hidden labor and broader social implications behind even seemingly straightforward religious imagery. Seeing how art functions within these material and economic structures transforms our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.