paper, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

16_19th-century

#

paper

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

albumen-print

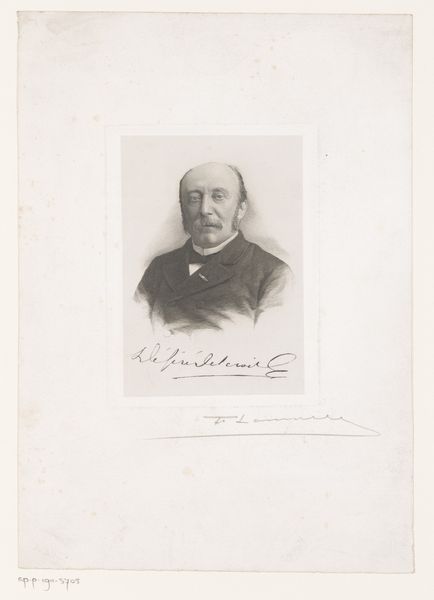

Dimensions: 22.7 × 18.2 cm (image/paper); 34.2 × 26.1 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

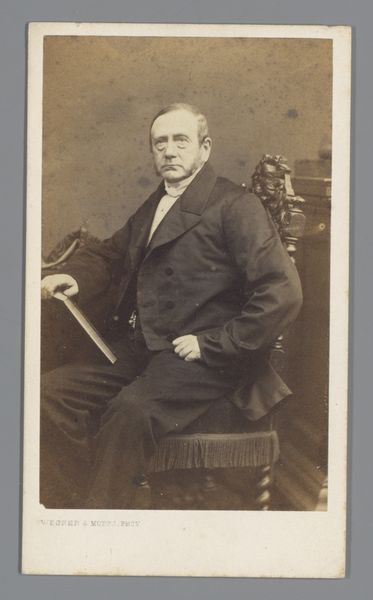

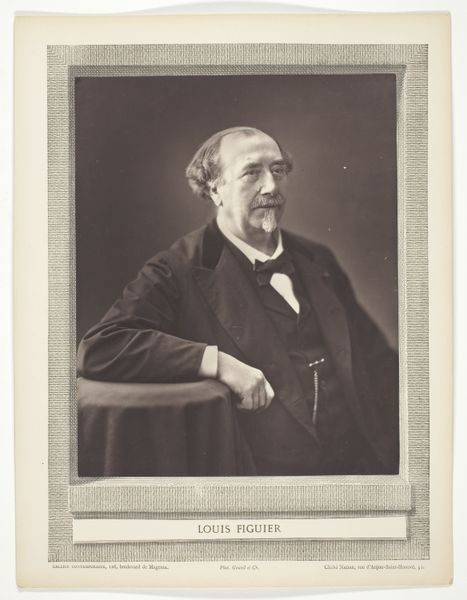

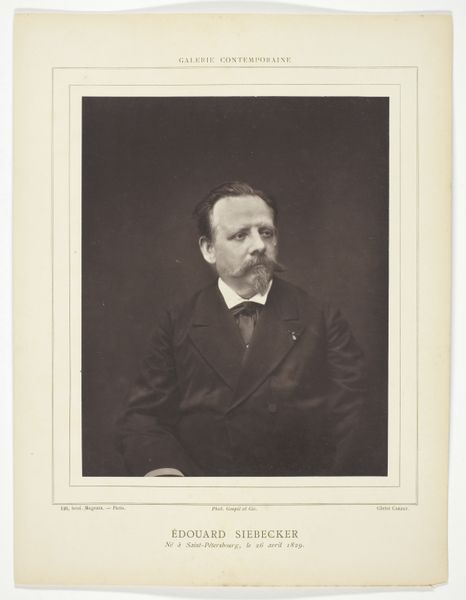

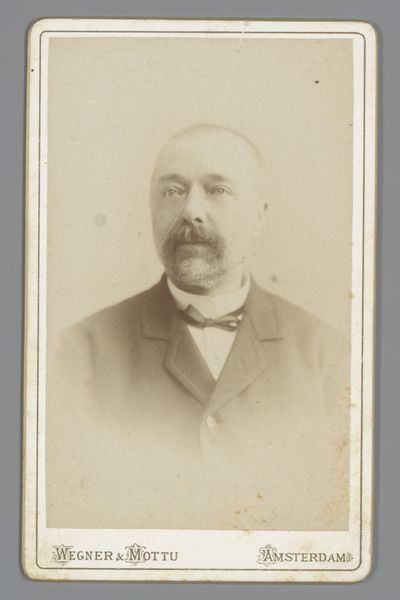

Curator: This is a portrait of Ferdinand Fabre, created by Nadar between 1853 and 1876. It’s an albumen print on paper, showcasing the photographic techniques of the era. Editor: There's something immediately striking about the gravity in his gaze, even in this reproduced form. It communicates a distinct air of bourgeois self-assurance from that time. Curator: Absolutely, Nadar was known for capturing the essence of his subjects. But let’s consider the albumen print itself— a process that involved coating paper with egg whites to create a glossy surface for the photographic emulsion. It was a labor-intensive method, reflective of the artisanal nature of early photography. The photograph becomes this record, then. Editor: Indeed, this "artisanal nature" speaks volumes about class and access in 19th-century portraiture. Who was given the privilege of representation and how does that connect to societal power structures at the time? What narratives were deliberately excluded through portraiture choices and why? Curator: Considering the social context, the rise of photography also democratized portraiture to some extent, providing an alternative to expensive painted portraits, yet access would have still been limited to those who could afford it. The final product would also rely on various studios involved in each step. Editor: Exactly, how does this process impact the understanding of authenticity within the art piece itself? Is it really about the artist's perspective or the studio, the process of albumen, or simply the depicted sitter in this piece? I like the framing; it adds to the sense of carefully constructed image. Curator: The framing indeed offers another layer to our examination. As a visual marker, this directs attention toward how such images circulated and were consumed. It’s not merely a photograph, it’s a carefully crafted product, that exists now because of archives and collection. Editor: Agreed, it prompts us to consider how portraiture functioned within the theater of social performance of that period, and question who exactly was controlling the narrative, not to mention whose story got told at all. Curator: Looking closely, we can analyze the material qualities to discuss that complexity, too, and how each albumen layer serves that final look of social performance within the depicted person. Editor: This image allows us to remember, examine, and resist these unequal modes of representation while moving forward to change existing dynamics. Curator: A powerful statement. By looking at the portrait both as a material object and as a social artifact, we gain a richer understanding of its meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.