Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

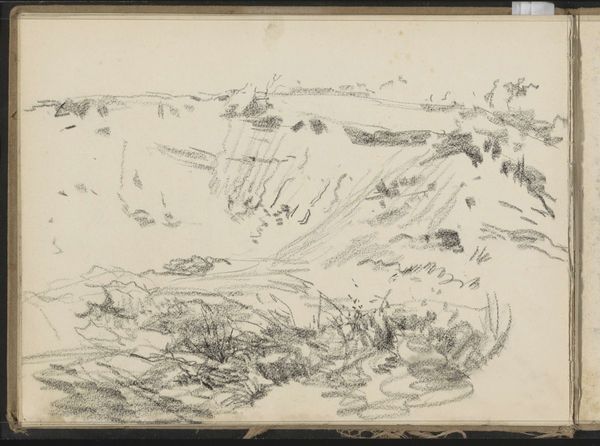

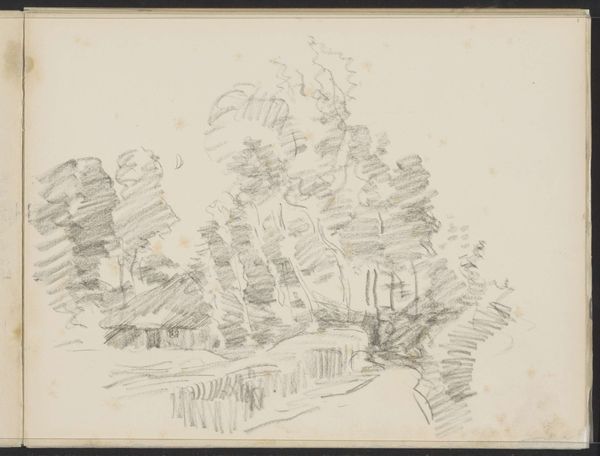

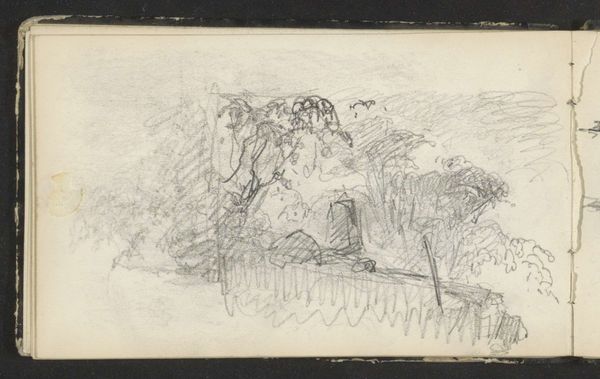

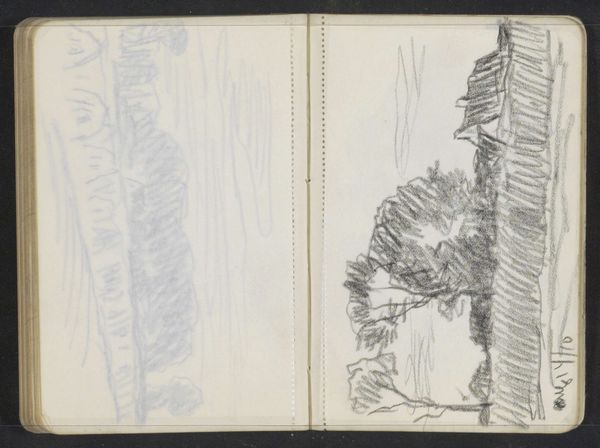

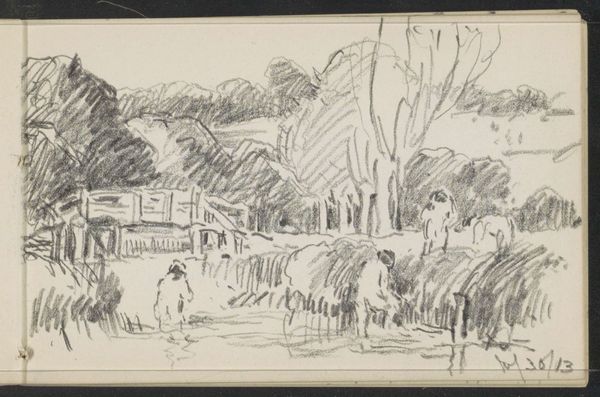

Curator: Willem Bastiaan Tholen's pencil drawing, "Man in a Hilly Landscape," estimated to be from between 1870 and 1931, is an unassuming piece. The rapid strokes give it an almost unfinished feel, doesn't it? Editor: It does. It’s a fleeting moment, almost dreamlike. There's a contemplative quality to the seated figure. I wonder about his relationship to this landscape, is he a farmer surveying his land or a traveler taking rest? What does the possibility of representing him even mean in his time? Curator: Tholen's known for his landscapes, seascapes, and cityscapes. It's as if he wants to capture the feeling of being there, right in that instant of seeing it for the first time. I suppose that might have been an aesthetic attempt at challenging traditional ideas of land ownership by creating something almost everyone has acess to when they observe a landscape: the representation of ownership through memory, personal reflection and the simple possibility of watching something. Editor: Memory feels pertinent to understanding art from that time: we must not forget that a whole European war and expansion happened during Tholen's artistic practice. Was his work influenced by a nostalgic yearn to return to the stability of pre-industrial or imperial expansion? Who is the man looking at? Does he own the land or is it another thing? Is Tholen simply representing it? Is this related to colonial depiction and aesthetic appreciation of appropriated lands? The implications in terms of politics of land and colonial imagination are enormous, if we think about it. Curator: Maybe. Or maybe it's just a moment of quiet contemplation. You know, Tholen loved working 'en plein air'. Could the image express a sensation more connected to being physically there in the natural setting instead of claiming social or political commentaries about his work, particularly if we consider he never overtly touches such themes? The very act of sketching directly from nature—so vital for the Impressionists—feels pretty subversive when you place it in its art historical context. Editor: True. And this reminds me that the artistic and bohemian circles to which he may have belonged embraced notions of freedom, artistic expression, and radical societal transformations, questioning old political orders in their own terms. Curator: Indeed. It also reminds us how simple lines can evoke something much larger, something to grapple with even after centuries, no? Editor: Yes, how we, as contemporary observers, are so influenced by intersectional discourses that viewing is also an act of re-imagination that comes with every encounter. It speaks volumes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.