print, etching

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

line

#

cityscape

#

realism

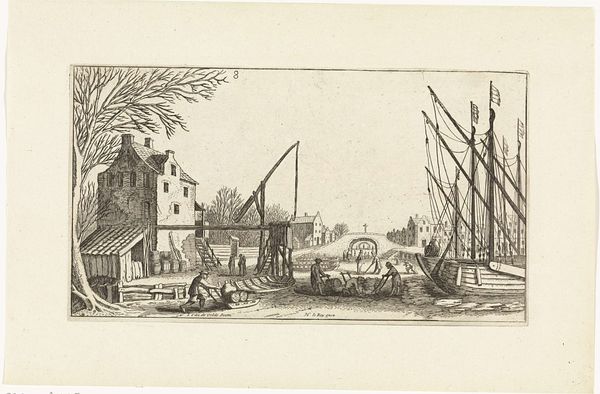

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

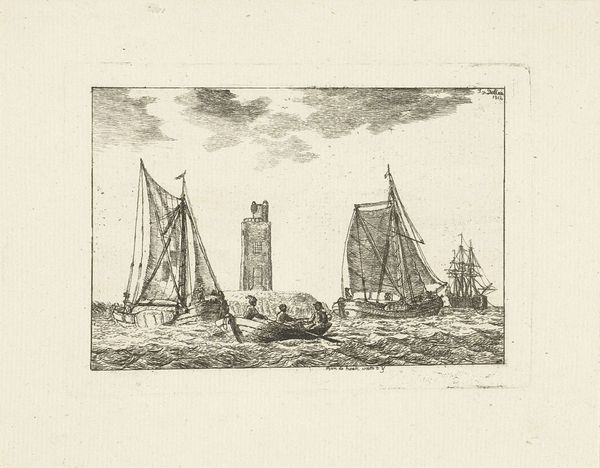

Curator: The fine lines and subtle tones really capture a tranquil river scene; it feels like a memory resurfacing. Editor: It does. There’s a distinct romantic sensibility to the scene. The Dutch Golden Age influence is definitely palpable, but the soft etching pushes it further towards Romanticism. I wonder, how does this etching, entitled 'Stadsgezicht met toren aan rivier,' fit within Johannes van Cuylenburgh's broader oeuvre, especially given its estimated creation date between 1803 and 1841? Curator: Cuylenburgh seems drawn to familiar, archetypal images. Here we have the city reflected in the water—a symbolic bridge between the mundane and the sublime. These forms represent shelter and power and continuity of community. Notice the detailed etching of the figures in the small boat—carrying echoes of Charon ferrying souls, maybe a meditation on human movement within a wider historical flow. Editor: That's a fascinating take! And thinking about human movement— who gets to participate in or access these idealized cityscapes, historically? These serene scenes often mask complex power dynamics that determined who lived where and who had access to these waterways, or to the commerce represented by the river traffic, visible through the faint lines in the background. Curator: Of course. Even idyllic scenes bear the weight of the society that produced them. Editor: Exactly. We can almost smell the mercantilism— this pursuit of “the good life” on stolen land with exploited labor. Curator: All the same, despite those problematic readings, the central tower dominates, its form almost primal, evoking images of protection and observation spanning centuries. The delicate details of the cityscape act like psychological imprints— they connect viewers through a visual language that bypasses specific historical context. The churches and town, as universal visual codes, carry these echoes. Editor: I suppose my activist lens seeks to constantly reveal these histories and contextualize their imagery within systems of domination. Cuylenburgh’s etching, though beautiful, can’t escape its connection to that historical and political narrative. Curator: I suppose these images serve both to remember our ideals, while activists serve to question our relationship with them. Editor: In a way, by questioning, we're also shaping the cultural memory and continuity that you spoke of at the beginning, one that includes the lives of everyone, and especially those erased from view. Curator: Hopefully that shapes how we see not just these etchings, but ourselves too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.