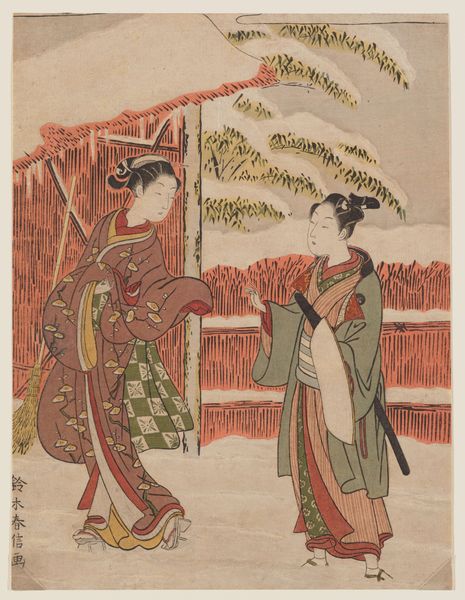

The Oiran Chōzan of Chōjiya, from the series Love Letters 1759 - 1779

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

#

narrative-art

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

erotic-art

Dimensions: Hosoe: 12 3/4 x 6 in. (32.4 x 15.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This lovely woodblock print is entitled "The Oiran Chozan of Chojiya, from the series Love Letters" and it comes to us from the hand of Ippitsusai Buncho. Scholars believe it was created sometime between 1759 and 1779. It's part of the impressive collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you most about this work? Editor: I'm immediately struck by the overall tone – a subdued and almost melancholic atmosphere, created by the cool grays and muted oranges, almost as though these women are existing on the margins. Curator: Note how the artist manipulates line and form. Consider the careful modulation in the lines defining the women's kimonos versus the more amorphous treatment of the falling cherry blossoms. The artist creates spatial depth, even within the constraints of the woodblock medium. It's a masterful orchestration of visual elements. Editor: Absolutely, and it invites a closer look into the lives of courtesans in the Edo period, prompting a reconsideration of the societal expectations placed upon these women. Ukiyo-e prints often romanticize these figures, but beneath that veneer, there's a rigid social hierarchy. What agency did these women really possess within this world of "love letters"? The erotic art from that time invites discourse between objectification and the social status of these figures in Japanese history. Curator: You raise a complex point. We can indeed look closely into what erotic art implies and signifies beyond face value. However, what is truly exciting in Bunchō's work here is in how he arranges compositional forms to explore surface pattern as depth, which moves far beyond questions about representation. I encourage listeners to step closer, ignoring the figures to see how form and surface merge through tonal graduation, repetition, and counterpoint. Editor: And I think it is impossible to disregard what this form carries: historical, and societal constructs for a whole generation of people for a very specific moment in time. In the end, Bunchō provides a poignant commentary on the constraints and performance expected of women in the pleasure districts of Edo Japan. Curator: Very astute points; however, there is pleasure for the eye here in seeing Bunchō explore spatial awareness through form, repetition, and a unique ability to make visual structure also symbolize the artist’s interior space and subjective reaction. Editor: Yes, I suppose this contrast in form and context underscores the very ambiguity that art embodies so well. Curator: A thought I fully endorse.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.