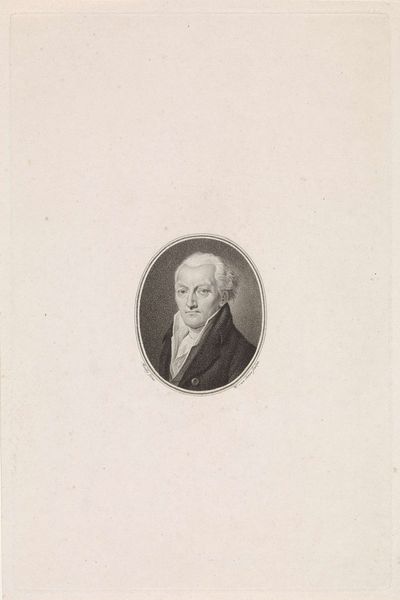

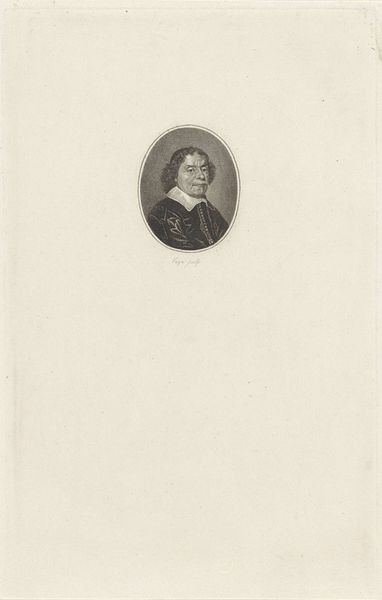

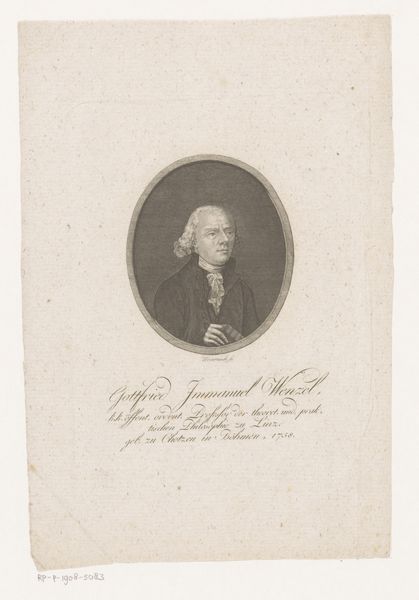

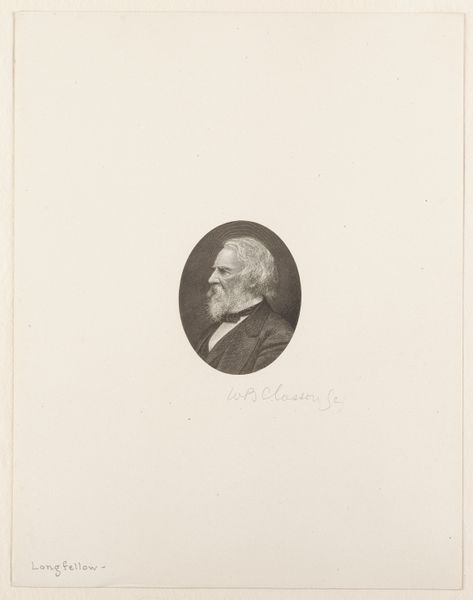

drawing, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

old engraving style

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil work

#

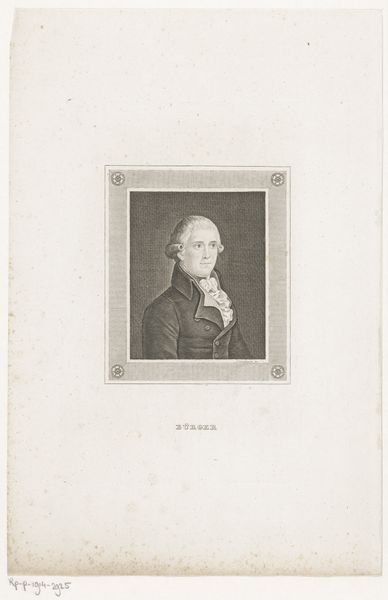

engraving

Dimensions: height 233 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Reinier Vinkeles' 1789 engraving, "Portret van Willem Antony van Vloten," housed in the Rijksmuseum. There's a stillness to it, a formality typical of portraits, but also an intriguing directness in his gaze. What can you tell me about it? Curator: That directness is key. The late 18th century was a period of immense social upheaval, particularly questioning the established order. A portrait like this, ostensibly a simple depiction of a man, becomes a site of negotiation. Consider the subject: Willem Antony van Vloten. Who was he? What did it mean to commission or be represented in this way during a time of revolution? Editor: I don't know much about him...so much I am still learning. It looks very austere...a little… republican almost. Curator: Exactly! Think about the historical context: the Enlightenment ideals circulating at the time. There's a rejection of overt aristocratic display, favouring a kind of sober virtue. But then look closer. The wig, for example. Still present, but arguably more restrained. Is this a conscious statement? How do we interpret that tension between tradition and nascent revolutionary sentiment? The way that Vinkeles renders fabric gives a strong sense of the sitter's...rooted presence. Does the colour, being reddish, contrast with the values represented? Editor: So, you're saying even within the constraints of portraiture, and in a very small format, an artist and sitter could signal their political leanings and social position? Curator: Precisely! These images are rarely neutral. And what does it mean that the print medium makes the image very reproducible. The power and reach of print should be at the foreground of our understanding. Art is enmeshed in power dynamics, actively shaping perceptions and reinforcing – or challenging – societal norms. Editor: I never thought about portraiture that way, but this has completely reshaped how I see this engraving. I suppose that the scale may have impacted his view; a larger canvas may be perceived differently in our current times. Curator: And that's the power of engaging with art through a critical lens. It encourages us to question the narratives we inherit and to actively participate in shaping new ones. It starts with questioning ourselves what each shade represented in art history represented in people's cultural behaviour.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.