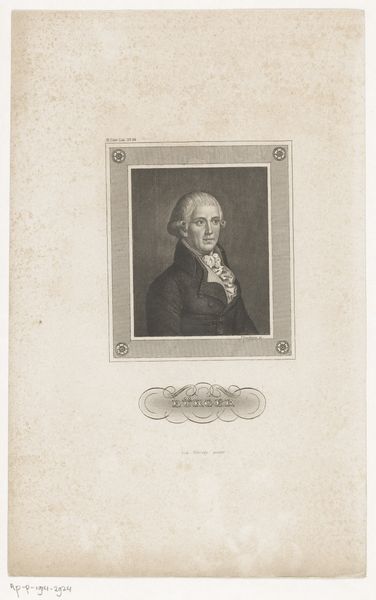

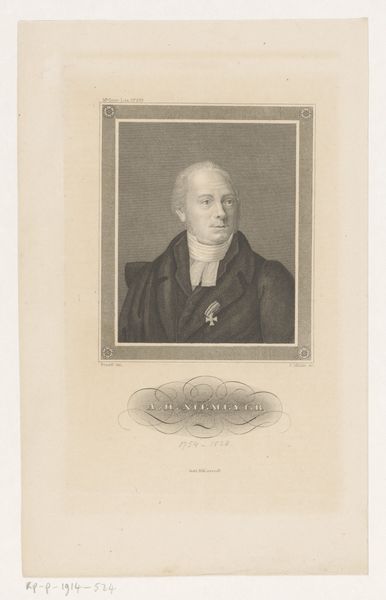

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 116 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this detailed engraving from the early 19th century, we see Friedrich Fleischmann's "Portret van Gottfried August Bürger," held here at the Rijksmuseum. It dates between 1801 and 1834. Editor: First thought? There’s something almost unsettling about his gaze, yet softened by the ornate frame around the portrait. It’s formal, yes, but with a subtle hint of vulnerability, like a carefully composed poem hiding a deeper emotion. Curator: Considering it's an engraving, think of the painstaking labor involved. Each line, each dot creating the shading, all contribute to the texture and form. Fleischmann had to understand not just Bürger’s likeness, but how that could be translated through the very physical act of mark-making with his tools. It represents the value placed on skilled craftsmanship during that period. Editor: And that stark contrast emphasizes the weight and seriousness often associated with formal portraiture, like carving someone’s importance into history with your own two hands. Curator: Indeed, portraits like these acted as social documents, meant for dissemination and consumption among a literate, largely bourgeois public. They helped shape the cultural memory and legacy of the depicted individual—in this case, Gottfried August Bürger. Editor: So, did it work? I mean, without context, would we necessarily grasp Bürger’s significance? Maybe it speaks to how portraits transcend pure likeness; it's about the aura, the social imprint a person leaves, regardless of later fame or obscurity. This man’s existence made ripples. This image—the way the jacket falls, or the intricate floral details in the corner—hints that all experiences, whether material or imaginative, get physically impressed upon us. Curator: An interesting idea. It invites reflection, then, on not only how likenesses like these once served a material function but also the way these objects subtly convey information about their subjects in their making and use. Editor: Ultimately, these artworks reveal that every stroke, choice of material, or commission tells stories, even centuries after the fact. Maybe even unintended stories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.