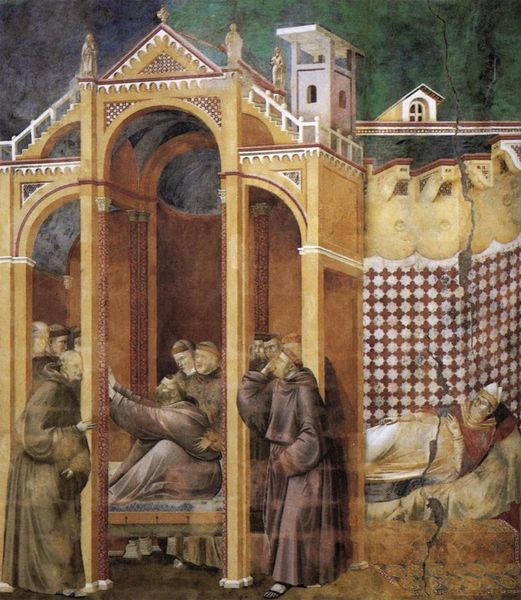

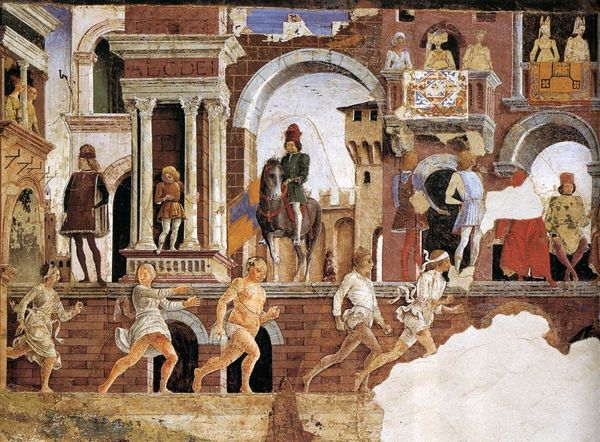

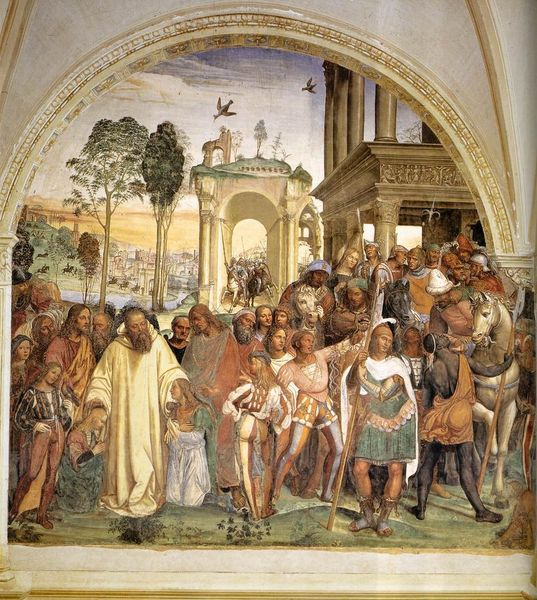

fresco

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

landscape

#

fresco

#

coloured pencil

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

christ

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: This fragment, titled "Adoration," comes to us from Albrecht Durer, around 1504. It is a fresco now housed in the Uffizi Gallery. My initial response is bewilderment. There's a strange collision of architectural grandeur and near-cartoonish figures, all filtered through this aged, almost ghostly palette. Editor: Well, before dismissing those "cartoonish figures," let’s consider Durer's context. His travel to Italy exposed him to the Renaissance’s rebirth of classical art. However, his German sensibilities clashed with idealized beauty norms. This friction gave birth to unique expressions of form and figuration. Perhaps this contrast is intentional, maybe it’s an artist exploring what art could and should become, against cultural expectations? Curator: Interesting perspective. I’ve always found his representation of religious scenes unconventional; especially considering the conventions around "Adoration". There's such narrative disjunction—scenes of possible battle beside scenes of rest? The characters are ambiguously rendered: Who are these people? Are they important characters or a landscape of general passers-by? Is he making a point that everyone deserves reverence or that violence and piety often clash, but share a landscape? Editor: Indeed, there's something deeply unsettling in this contrast that complicates conventional religious narratives. Also note how Durer situates this holy event within a decaying classical structure. This ruin serves as a silent commentator on the transience of earthly empires, standing in stark contrast to the enduring promise of the spiritual realm. Is it not an appeal to a more lasting form of value? Curator: That's perceptive. It suggests Durer was interested in more than just religious themes, potentially interrogating political systems. The ruined architecture—the armies passing in front of it—speak to temporal power. It also suggests the cyclical nature of history; rise and fall are consistent and equally relevant in considering history and spirituality. Editor: Absolutely. I’d go so far to ask, given its deteriorated state and our limited fragment, how our incomplete viewing challenges conventional interpretations of power dynamics and allows for a more nuanced discussion of the fragmented identities of the figures involved. How might gender or racial stereotypes be complicated by this fragmented perspective? Curator: It truly destabilizes everything. And how intriguing that even after centuries, Durer’s "Adoration" manages to ignite critical dialogue about faith, politics, identity, and art history's role. Editor: Leaving us to ponder if a fragmented past helps illuminate a more comprehensive future?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.