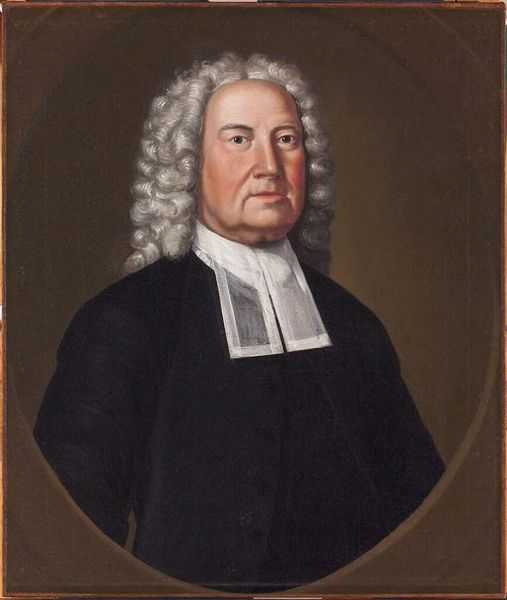

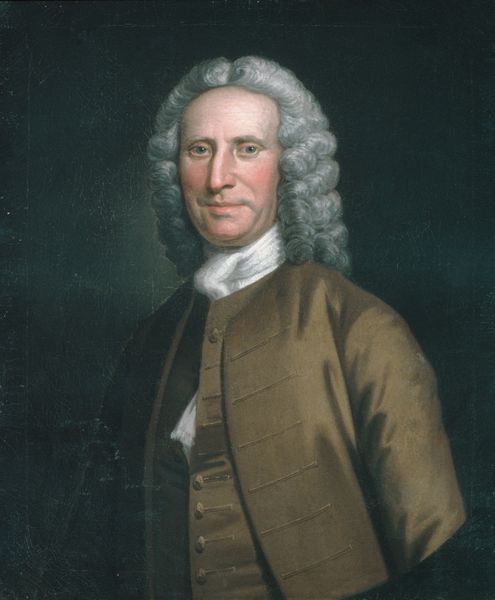

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

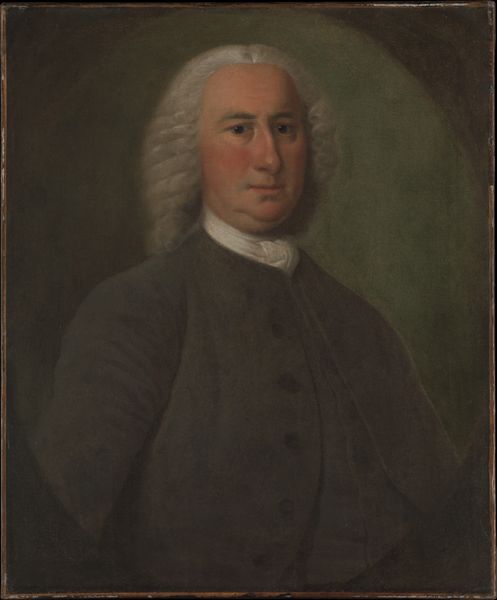

Curator: Staring back at us from the 18th century, we have John Wollaston's "Joseph Reade," painted between 1749 and 1752. It now resides here, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first thought? Sepia. Everything about it seems to have been dipped in shades of brown. It feels…grounded, perhaps even a tad severe? Curator: It's the earthiness of the materials, isn't it? Look at the way Wollaston layers his oils – that glazing technique, building up the shadows… And think about where those pigments came from, probably ground by hand. There's real labor embedded in this image. Editor: You can almost feel the weight of that wig, the texture of his waistcoat. It must have taken the sitter hours to pose for it, or even longer to produce the cloth. And did Wollaston even mix the colors? Perhaps he also had assistance, like any craftsman in a production line, like buttons for clothing… Curator: You know, his eyes. I find his eyes almost luminous, as if reflecting an inner light. There's a quiet intelligence there, a hint of something… wistful? Editor: I find them unnervingly uniform to a modern eye, perhaps all the sitters looked just alike… the painter only produced this face? It might speak to something in standardized early capitalistic society when everyone is the same because there is not the diversity of choices like there is now. But it certainly does speak to that moment, that era where portraiture cemented one's status, visually reinforcing power structures of that era. Each brushstroke a tiny brick in the edifice of colonial society. Curator: It's funny, isn’t it? We see a stoic portrait; you see a mirror reflecting the mechanisms of power. And yet, somehow, both realities exist simultaneously on this canvas. Wollaston gives us a glimpse, if nothing more. Editor: Art, as an expression, is never innocent—just labor to be exploited under particular power structure to produce and maintain an imagined society. Seeing these brushstrokes not as art, but instead a relic. It does change our point of view of a time so far away, yet whose ripple effects are still with us now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.