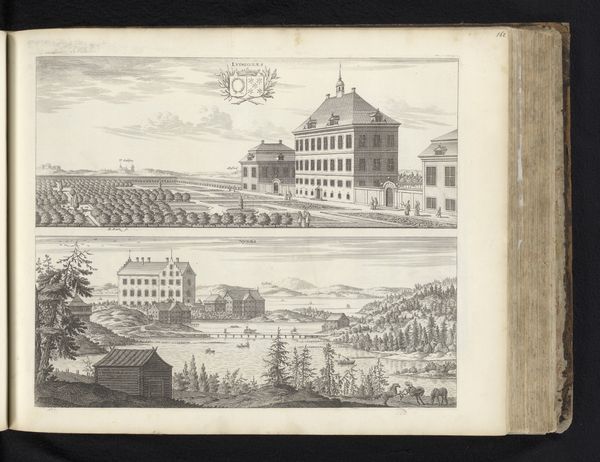

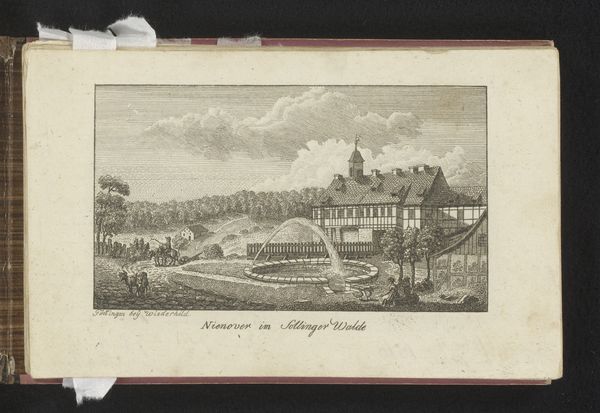

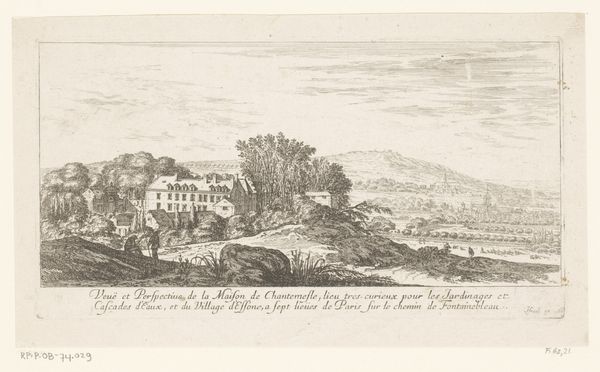

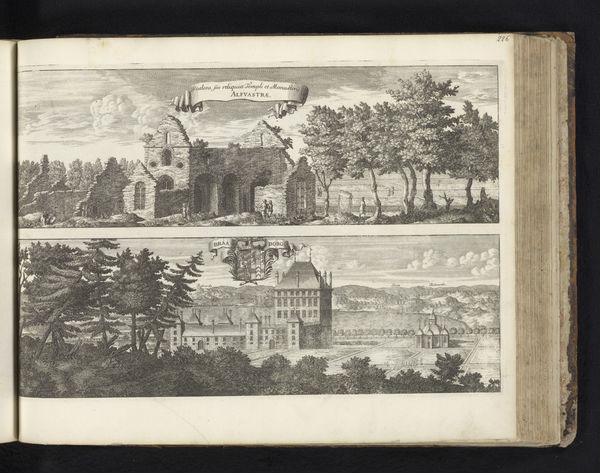

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

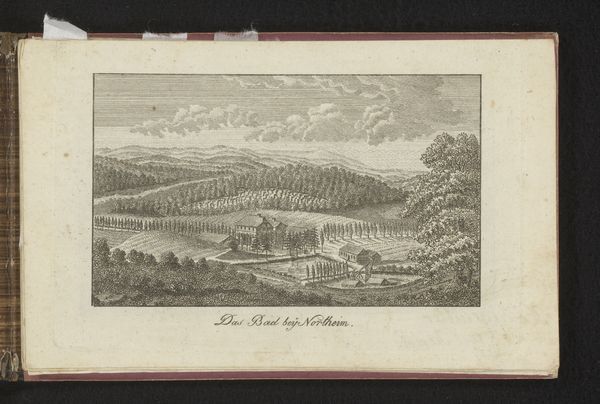

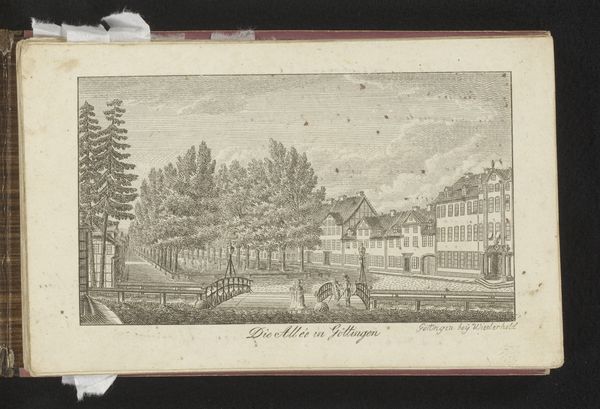

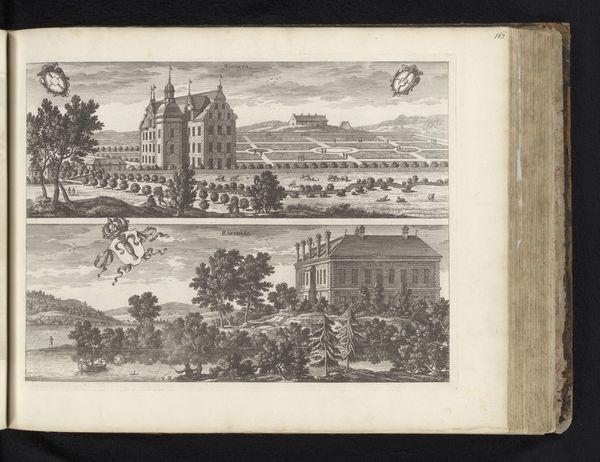

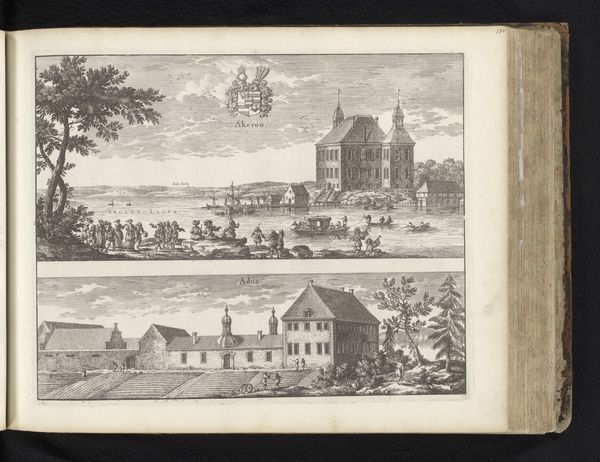

landscape

#

coloured pencil

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a piece titled "Gezicht op het Bergpark en Schloss Wilhelmshöhe nabij Kassel," created sometime between 1770 and 1816 by an anonymous artist. It's a landscape print, achieved through engraving, demonstrating a keen engagement with neoclassical ideals. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its overwhelming sense of order and control. The rigid geometry of the architecture against the seemingly tamed landscape evokes power and dominion. What sort of statement was this landscape intended to make? Curator: It certainly presents a visual language steeped in authority. Neoclassicism frequently drew on architectural and aesthetic symbols of ancient Greece and Rome to legitimize contemporary regimes and promote stability. It served as a statement of cultural aspiration, harkening back to the perceived glories of the ancient world. The engraving itself adds to the visual message. What associations does the medium evoke for you? Editor: The medium’s clean lines contribute to the sense of rational mastery over nature. But beyond the visual precision, it makes me wonder who had access to such imagery. Was it meant to inspire awe and obedience in the general public or cater to the refined tastes of the elite? Curator: Very likely both. Images like this would circulate amongst the elite, solidifying their connection to an ideal of refined taste and legitimate rule. And beyond those immediate circles, consider its effect on burgeoning senses of nationhood—providing visual continuity by referencing prior cultural forms and systems of power. You can sense the way visual forms embed narratives across history. Editor: I agree. It serves as propaganda of sorts. But considering the time period, coinciding with the rise of revolutionary sentiment throughout Europe, what subtle resistance or reinterpretation might have been present among viewers outside the intended audience? Curator: That is precisely the fruitful terrain for inquiry. One might investigate, for example, how depictions of grand estates served to heighten class tensions and inadvertently contribute to discourses surrounding inequality. These engravings become far more potent artifacts when understood not only as records but also as active participants in societal dialogues. Editor: It all gives me so much to ponder regarding power, visual culture, and the narratives woven within landscapes. Thanks! Curator: Indeed. It makes you consider how visual languages reflect both intended statements and the shifting contexts in which such statements were always subject to debate and, inevitably, reinterpretation. Thank you, as well!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.