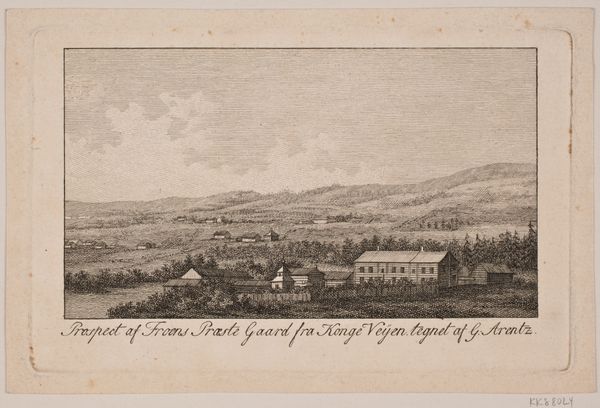

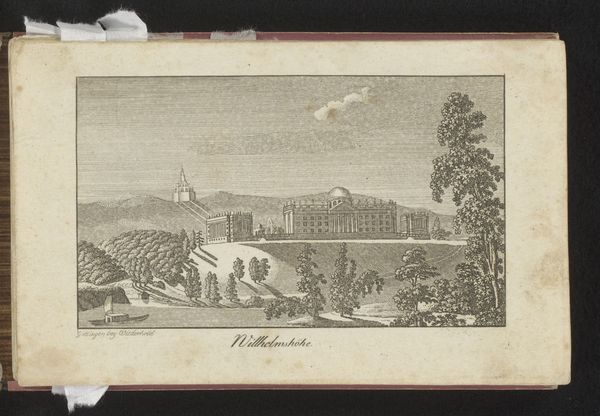

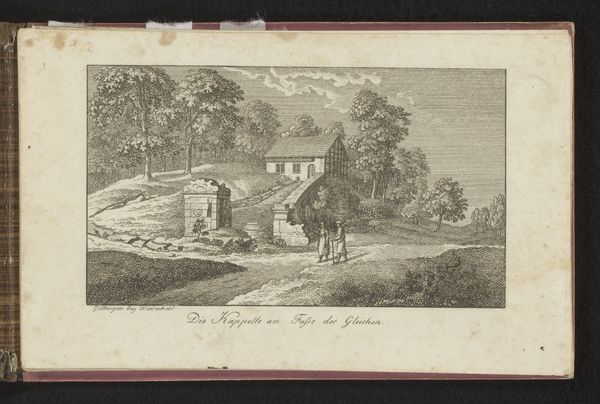

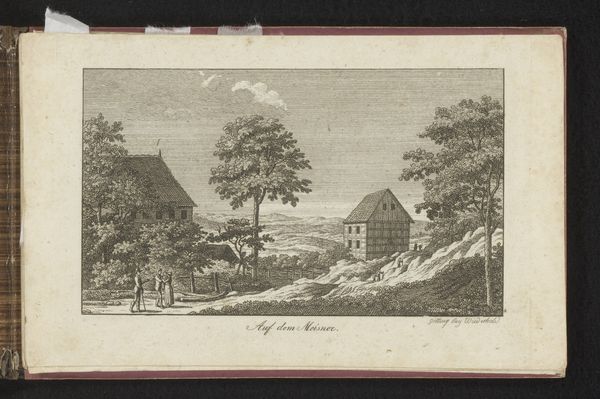

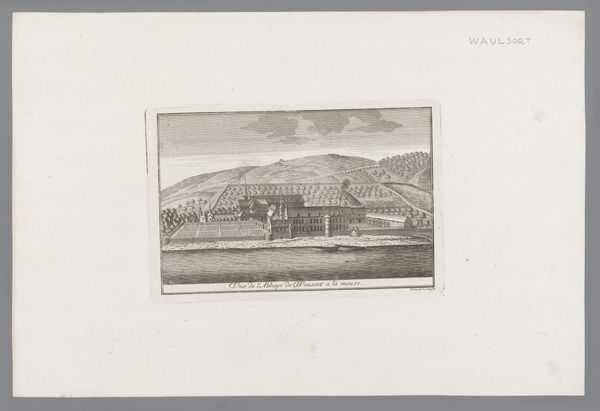

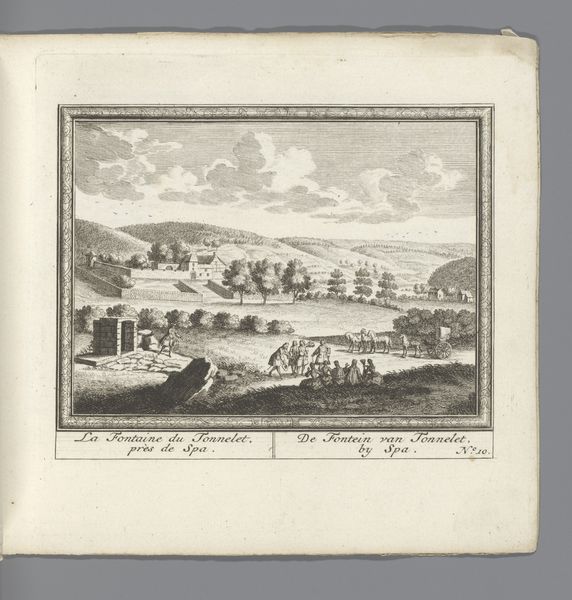

print, engraving

#

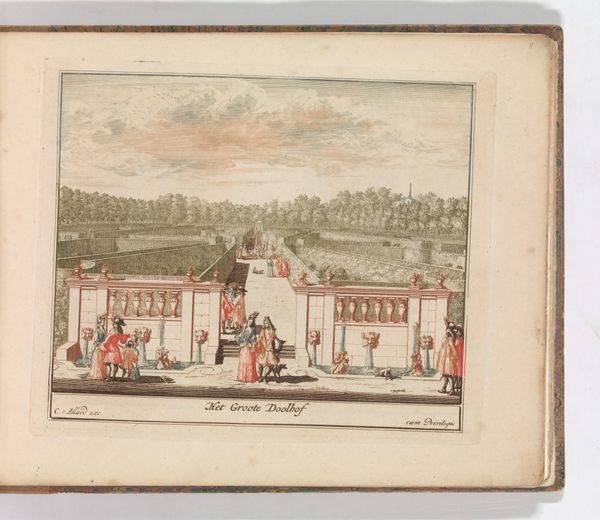

neoclacissism

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

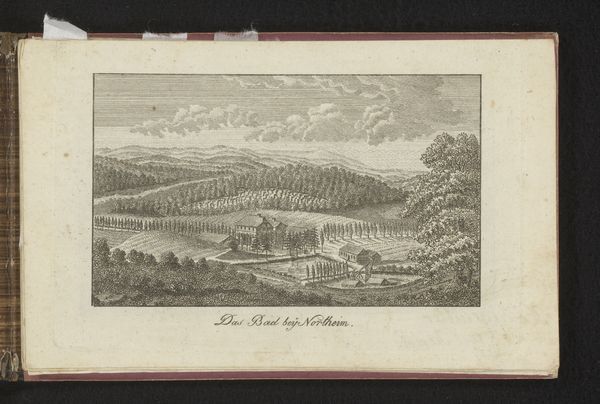

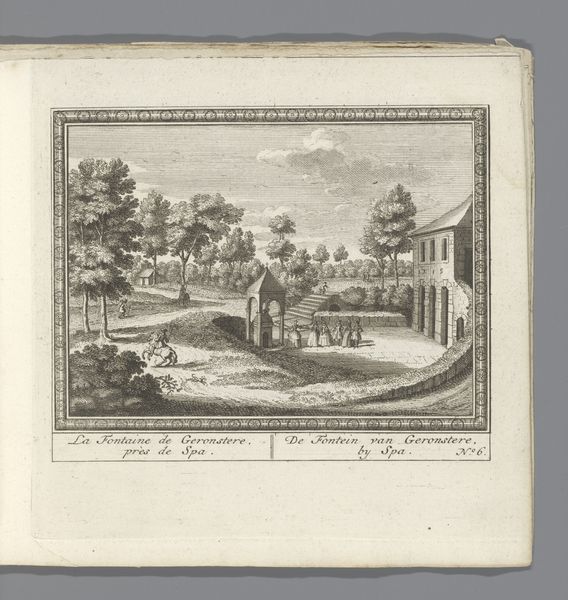

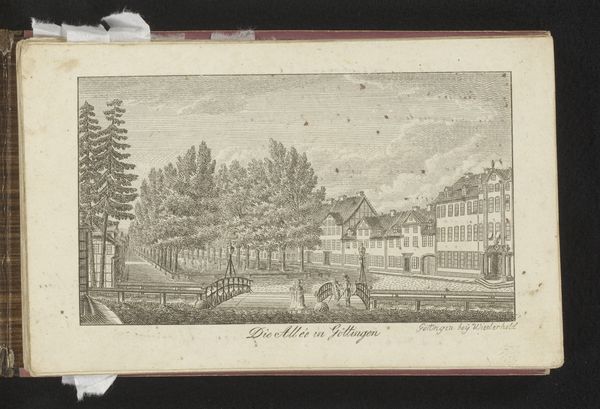

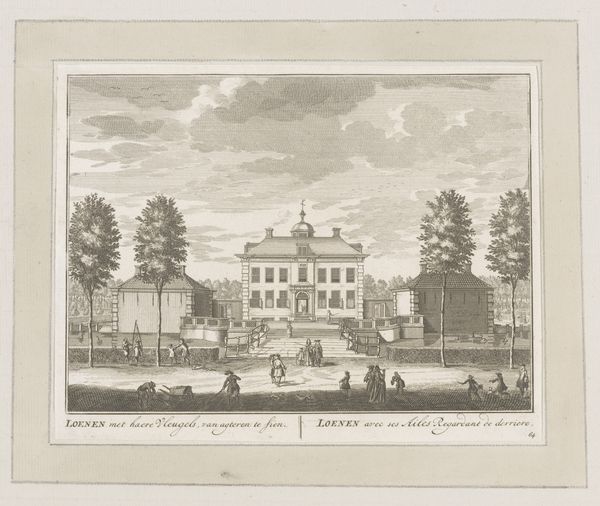

Curator: Let’s discuss "Gezicht op Nienover," a cityscape print created anonymously sometime between 1770 and 1816. The detailed engraving really caught my attention when it came into our collection. Editor: My initial impression is a tranquil one. Despite the meticulous detail in the architecture and landscape, there's a serene quality—a stillness that invites quiet contemplation, but also prompts questions about social strata during its making. Curator: Right, let's think about the making of this work as a print. The meticulous labor required for engraving, and the socio-economic dynamics within the printmaking industry at the time, considering printmaking was a vital tool for circulating knowledge and shaping public opinion during an era defined by radical societal shifts, such as political revolution and rising nationalism. Editor: The absence of a known author is especially interesting. Anonymity can be a potent act. Is this potentially the quiet resistance of an artisan excluded from the established art world, using print to disseminate a subversive narrative of landscape and society, accessible across socio-economic boundaries? Perhaps a form of cultural critique through seemingly neutral representation? Curator: Well, landscape prints in this period had very standardized styles. It is important to acknowledge the conventions and technologies of its time—the paper, the ink, the engraving techniques. How the material conditions shaped its production, distribution, and consumption, mirroring larger economic structures—this print, like so many, may have been about satisfying demand for views, and social position was tied to purchasing those prints, commissioning them even. Editor: Absolutely. Neoclassicism heavily influenced this piece; a very structured scene of nature with rational forms, however, it does bring to mind larger themes. We have a European country house, but how was this ideal made possible? Prints such as these mask a dark history of labor and social disparities and were often tools to promote ideologies. Curator: True. And thinking about production of these, these prints allowed access to art and scenes for broader society and became an engine for shaping broader taste through reproduction of these idealized views of classist hierarchy. It highlights not just artistic skill but the broader context of labor, consumption, and the circulation of images in the 18th and 19th centuries. Editor: In conclusion, while the surface seems like a gentle portrayal of a European locale, delving into its historical context uncovers the potential voices and forces at play, prompting reflection on societal structure through both obvious, and obscure messages embedded within the seemingly simple cityscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.