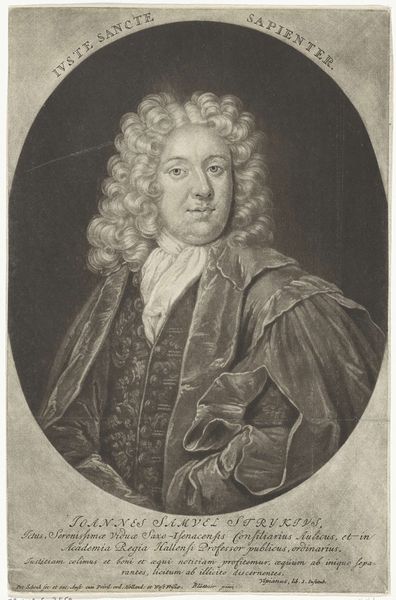

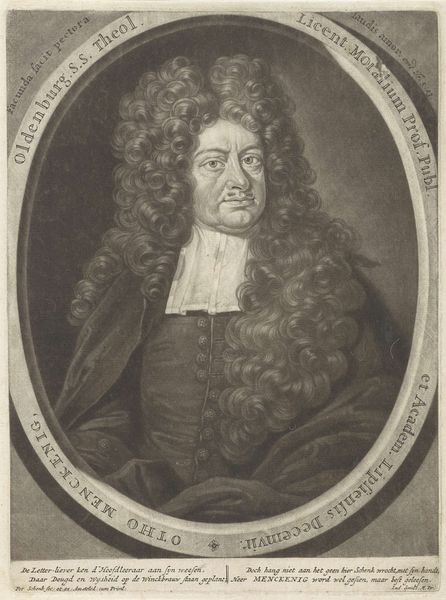

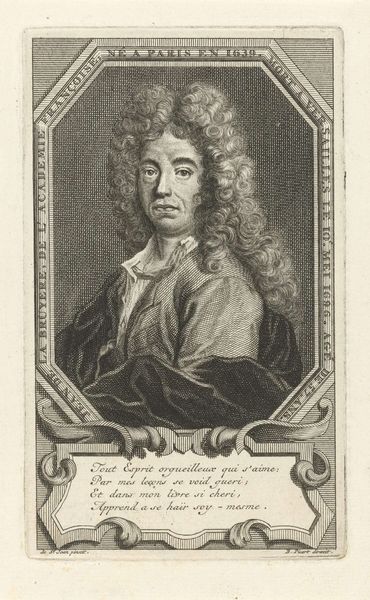

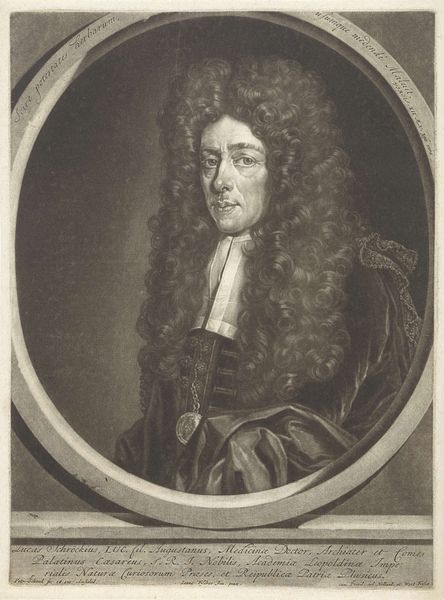

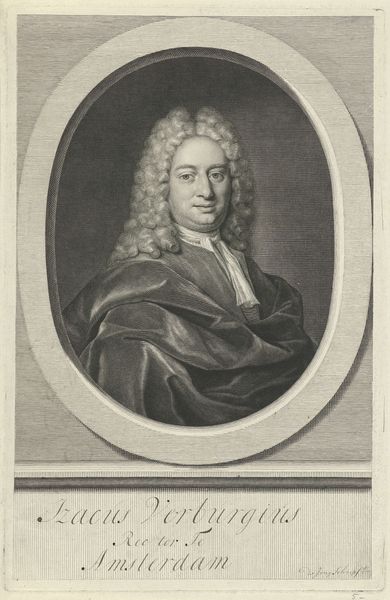

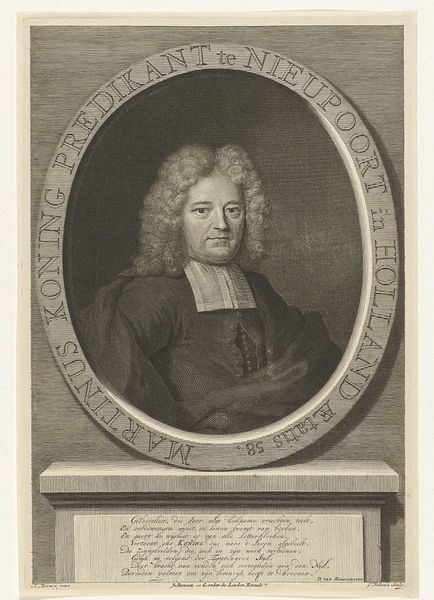

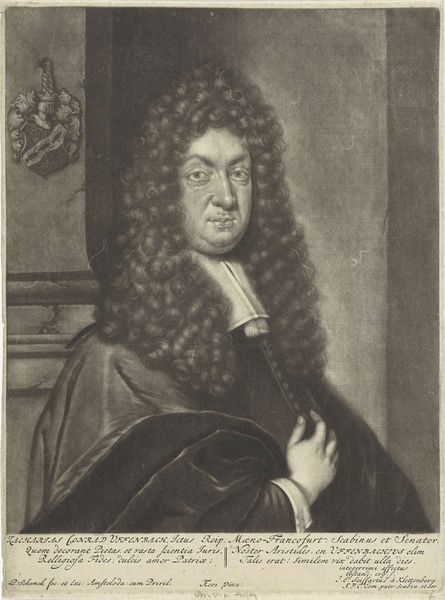

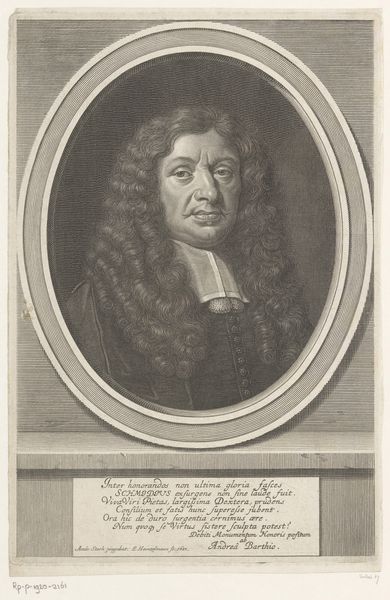

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 350 mm, width 256 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we see a print of "Portret van William Russell op 84-jarige leeftijd," dating from between 1700 and 1742, attributed to Robert Williams. My eye is immediately drawn to the almost overpowering sense of inherited power emanating from the subject's face. Editor: Overpowering is one word for it! I'm mostly struck by the textures at play here. Look at how the engraver replicated the lace and the volume of that truly enormous wig. How long did it take to create that intricate, repeatable pattern on his neck adornment? Curator: Precisely. The lace, the wig, it all speaks to status. But look closer; those symbols are working on multiple levels. The cascading curls create an almost god-like halo, immediately imbuing Russell with a particular kind of significance for the viewer. It links him, visually, to a chain of historical figures represented similarly. Editor: Yes, the layering of materials speaks to a conscious production of social hierarchy through laborious crafts. How many skilled hands and how much material wealth did it take to produce a man, coiffed and laced, who looked *precisely* like that? Each repetitive line is also indicative of the printmaking technology used to create multiple copies of the image and disseminate this carefully-constructed likeness across the land. Curator: That is the very crux of these Baroque portraits; the message amplified through skillful repetition. There is no casual depiction here; everything—the light, the composition, the deliberate symbols of office, even the careful recording of his lineage in the inscription at the base—contributes to a calculated image. It attempts to create an enduring idea, not just of a man, but of an inherited legacy. Editor: Exactly. Engravings such as these provided visual anchors for class structure and noble bloodlines that legitimized unequal material realities through aesthetics, craftsmanship, and even consumerism. I can almost see and feel the labor. Curator: Indeed. I'm left considering how potent these visual languages were, and arguably, still are, in shaping our understanding of power. Editor: I'm walking away thinking about how art and production intersected in this era and what "craft" really means in the definition of the so-called fine arts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.