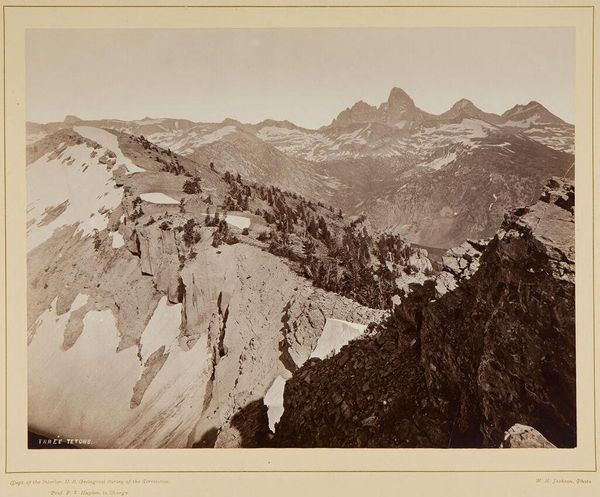

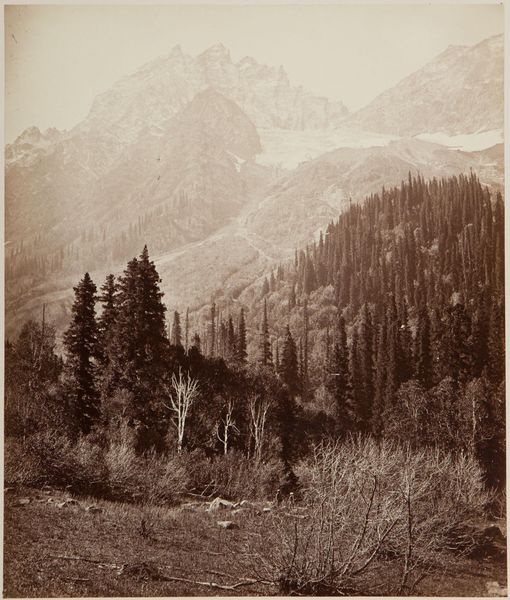

Dimensions: 10 x 12 15/16 in. (25.4 x 32.86 cm) (image)15 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. (39.37 x 50.17 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This albumen print, titled "The Three Téttons," was captured by William Henry Jackson around 1873. The albumen process involves using egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper, resulting in a unique tonal range. What strikes you about it initially? Editor: The sense of vastness, absolutely. But there’s also something…sepia-toned sadness to it. It feels like a captured moment of melancholy grandeur, and I'm instantly thinking about Manifest Destiny. Curator: Indeed. Considering its historical context, we can examine the production of albumen prints and the resources required: the paper, the silver, the labor to process each image. This reflects a period of significant resource extraction in the American West. The photograph functions as a commodity. Editor: And to connect this visually with the idea of commodification and settler colonialism, the monumental landscape also plays a crucial role in shaping national identity, one founded on the erasure of Indigenous presence. What's presented as empty wilderness was inhabited land. Curator: Precisely. The very act of photographing—the labor involved in transporting equipment, setting up in the field, developing the images—represents an imposition on the landscape. Jackson, who was employed by the US Geological Survey, wasn’t just making art; he was participating in resource mapping. Editor: This ties directly into discourses of power and knowledge. The photographic documentation wasn't simply for aesthetic appreciation, but also facilitated control over land and people. I think a close study of similar images by Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan reveals related techniques of ideological positioning within landscape imagery. Curator: I agree, and seeing these printed and bound in albums shows that the image became part of a viewing trend and part of domestic space. These were meant to be collected, viewed, and handled, changing them with constant use. The fingerprints, fading, and wear mark its utility. Editor: Yes, and beyond the pristine photographic surface, we can discern the stories and histories etched onto it—of both the materials used and the social narratives implicated in its making. Jackson wasn’s simply documenting a sublime wilderness, but also legitimizing the expansionist ideology of his time. Curator: Looking closely at the material reality alongside the image brings new context. Editor: And seeing its beauty with awareness reframes how we internalize these views.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.