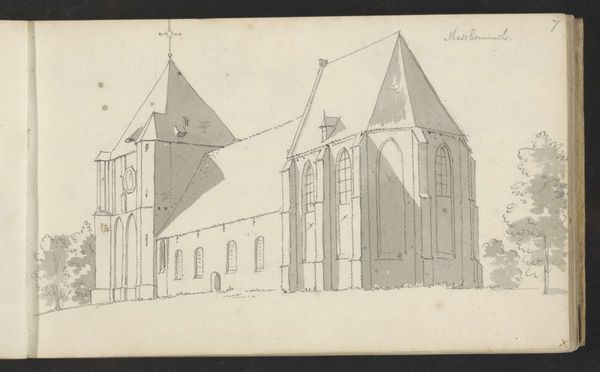

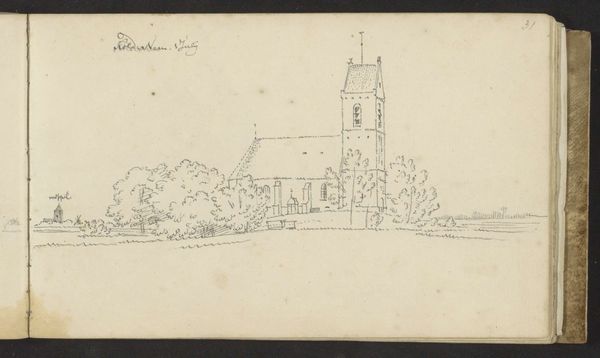

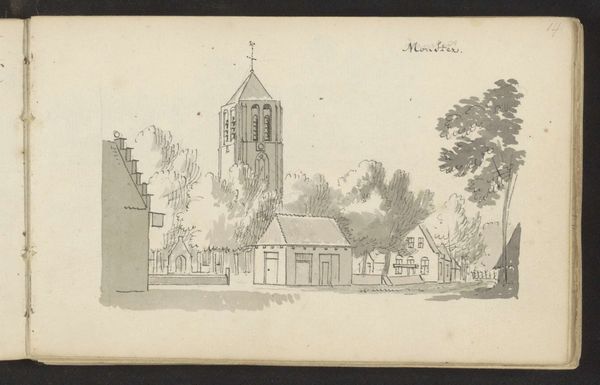

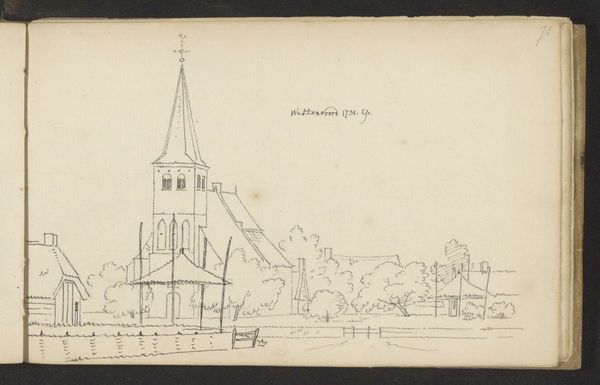

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

quirky sketch

#

baroque

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

paper

#

form

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

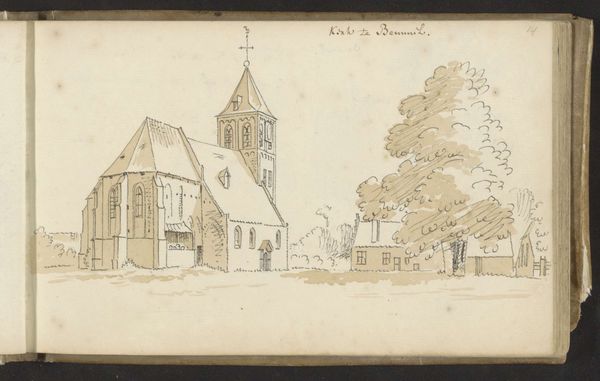

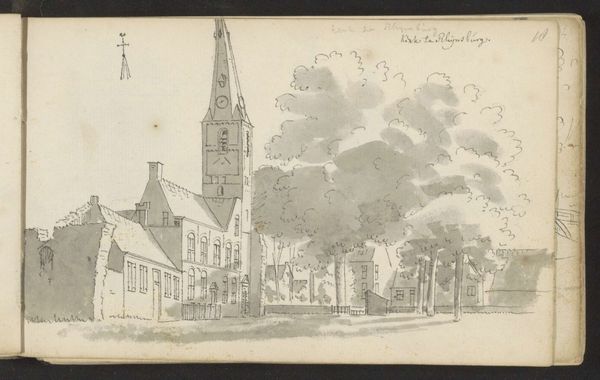

Curator: This pen-and-ink drawing, “Kerk te Voorthuizen,” possibly dating from 1732 to 1736, comes to us from the hand of Abraham de Haen the Younger. Currently residing at the Rijksmuseum, it offers a glimpse into the artist’s world and perhaps even the world of the average person at the time. Editor: There's something deeply calming about this sketch, wouldn't you agree? The way the light seems to catch the steeple, it’s as if the artist is sharing a quiet, personal moment of reverence or even just contemplation in their little sketchbook. Curator: Absolutely. Sketchbooks during the Baroque era served as portable observatories, if you will. Artists, like De Haen, used them not just for preliminary sketches, but to document the changing urban landscape and record their impressions of daily life. Consider this piece as a dialogue between personal reflection and documentary practice. Editor: Documentary, yes, but with such a light touch! The quirky lines almost dance on the aged paper, creating a whimsical quality, not usually associated with architectural studies. There's a lovely, subtle asymmetry at play, especially if you compare the different elements to the left and right sides. It creates a feeling of effortless freedom. Curator: And that asymmetry, perhaps unintentional, hints at a tension within Baroque conventions themselves—the pull between idealized form and the reality of a specific place and time. It's tempting to imagine De Haen, sitting somewhere nearby on the 27th of July—as written above the church itself!—recording this church as services went on, thus imbuing it with the dynamism of public life. Editor: Which speaks to something deeper, I think. The choice to sketch it from this specific angle, the deliberate simplicity of line, all adds up to the distinct possibility that it's a statement of humility—maybe even quiet resistance to the pomp and grandeur so typical of the Baroque era, using an intimate format instead to capture the essence of communal faith and human scale. Curator: A fascinating idea indeed! The drawing compels us to consider how De Haen saw his role in a rapidly changing world. He invites us to see how we are connected to both each other, to this place, and its complex history through the universality of a daily experience of time, whether that's visiting a church service, being mindful during travel, or pausing to appreciate the enduring forms and spaces humans have constructed. Editor: Beautifully put. It is an unassuming drawing that is open to a very wide range of interesting speculations about how it can relate to ourselves and human communities everywhere, then and now!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.