print, photography, architecture

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

architecture

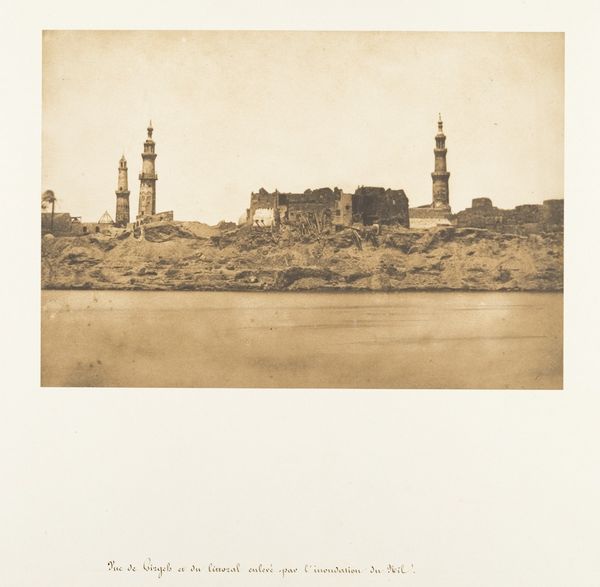

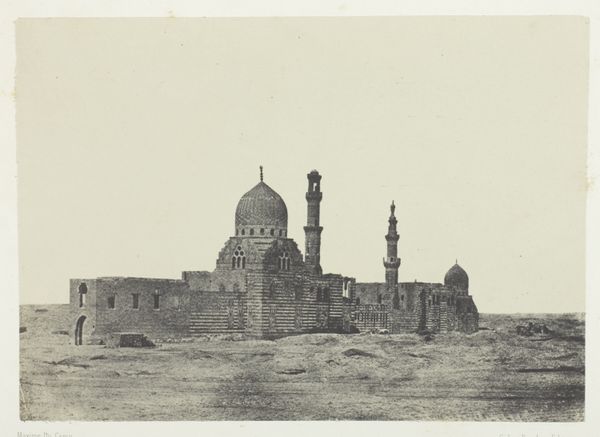

Dimensions: Image: 6 7/16 × 8 3/4 in. (16.3 × 22.3 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

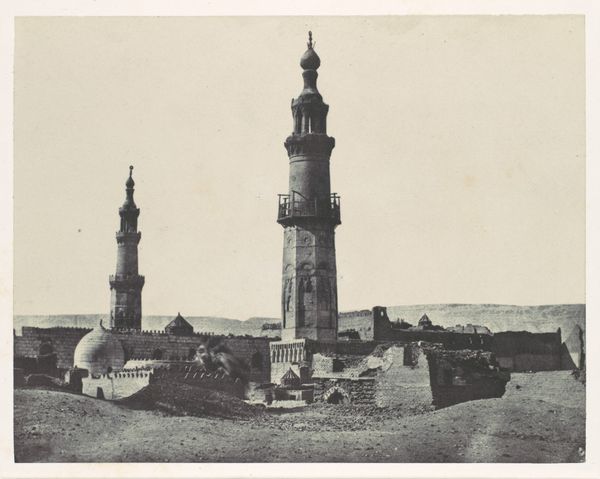

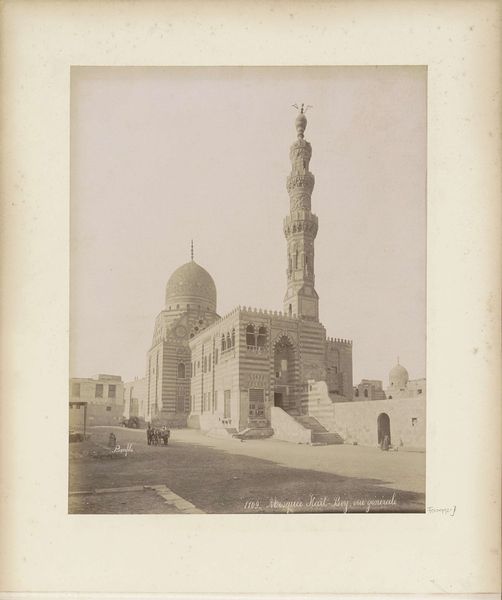

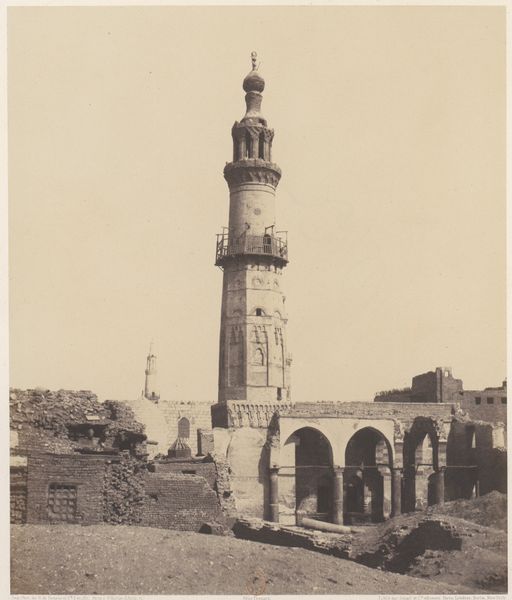

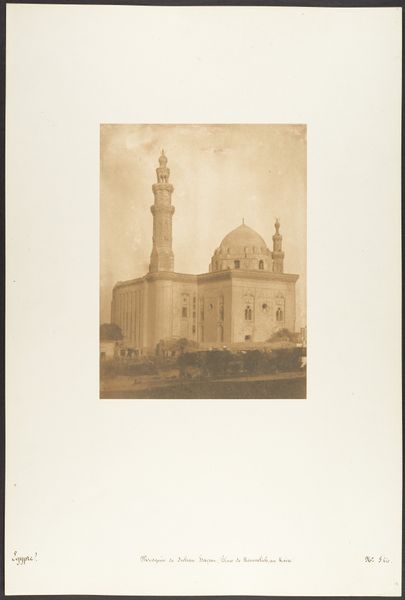

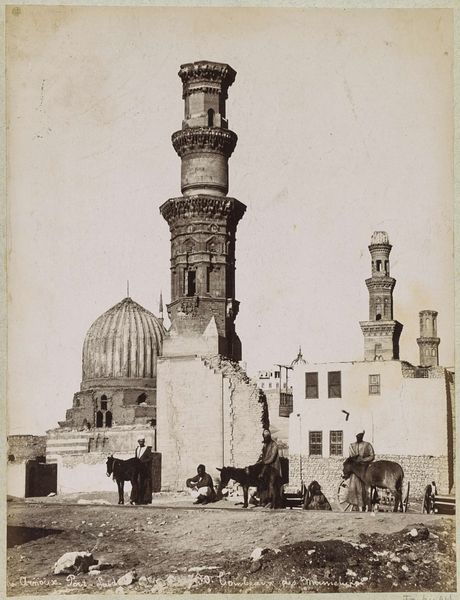

Editor: This is Maxime Du Camp's photograph, "Mosquée d'Ali-Bey, à Girgeh," taken around 1850. It’s a lovely sepia print depicting an old mosque in Egypt, and it's got such a stark, weathered feel. I'm struck by how the photograph almost seems to emphasize the decaying nature of the building, its materiality. What are your thoughts when you look at this? Curator: My attention is drawn to the materiality too; the print itself becomes a document of the social and material conditions surrounding its creation. Consider the labor involved. This photograph, like all early photography, represents a significant investment of time and resources. From the photographer's journey and equipment to the chemicals used, it signifies colonial dynamics. This wasn't merely an artistic endeavor; it was a form of visual inventory tied to broader imperial projects. How does understanding the resources inform our interpretation? Editor: So you're saying the act of photographing itself reflects something about colonial power, its need to catalogue and sort of, possess? I never really thought about it that way, but it makes sense that something seemingly so simple involved many different components with underlying agendas. It changes how I think about the image as a neutral documentation, I suppose. Curator: Precisely. Consider, too, the materials used. Early photography demanded expertise and often expensive equipment, highlighting a social stratification inherent even in artistic practices. Examining Du Camp’s process also invites us to consider accessibility and the implied audience. The photograph wasn't aimed at the people who occupied this mosque, and to that end it becomes part of a broader context. Editor: That is really insightful; it makes you think about the image not just as something pretty, but what that object can tell us about the broader historical and political context. I’ll remember to consider this “behind the scenes” aspect with other artworks too! Curator: And remember to always question the presumed neutrality of any historical documentation; often the means of production tells a revealing story itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.