painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

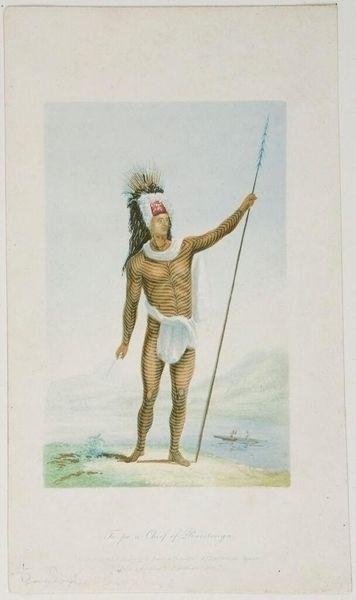

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 173 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today, we’re observing a watercolor painting by Ernest Alfred Hardouin, titled "Bathing Enslaved Javanese Woman," created sometime between 1837 and 1854. Editor: It's instantly melancholic, a poignant stillness captured in the figure’s posture and the muted color palette. The texture appears quite smooth despite the visual suggestion of a coarse wrap of patterned textile. Curator: Indeed. Let’s unpack this a bit further, shall we? The composition divides the space into distinct horizontal layers: water, steps, earth, and sky. The figure, though central, seems strangely small against this expanse. This emphasizes her vulnerability within the larger context. What statements are presented here about the semiotics of placement in colonial-era Indonesia? Editor: And look at the specifics of the water – it anchors the subject. It serves both a practical purpose – cleansing – and likely carries much symbolic weight for someone dispossessed of freedom, culture, and even control over their own body. It all seems to point to exploitation under colonial rule and it asks a hard question: who has power in the scene and over the scene? Also note the choice of watercolor: a fugitive medium for a fugitive experience. Curator: A rather astute observation regarding water, though perhaps slightly burdened with overt interpretation! Nonetheless, let’s address this technical nuance. Watercolor's transparency here isn't accidental; Hardouin would have recognized the value of depicting both physical and social transparency within Dutch colonial authority in Java. Also notice the subject's subtle positioning along what the photograph doesn’t easily capture as compositional symmetry and imbalance across light, shadow, and reflective visual forces. Editor: That emphasis is more than just technical, however. It highlights the power structures at play and serves as an important material component, right? It moves away from solely aesthetic contemplation and asks that the viewer engage with colonial history in Java. Curator: Perhaps, but I would argue that this method moves away from careful aesthetic judgments. Editor: A fair enough judgment. Thank you for clarifying those opposing positions today. Curator: You are most welcome.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.