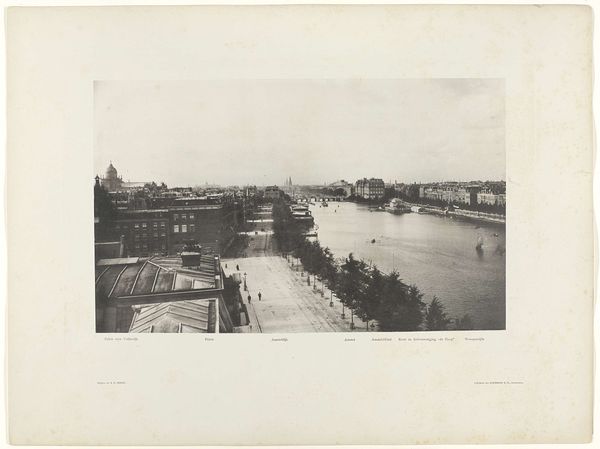

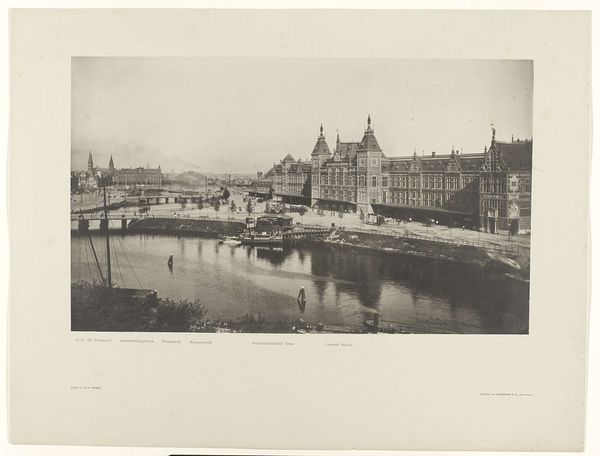

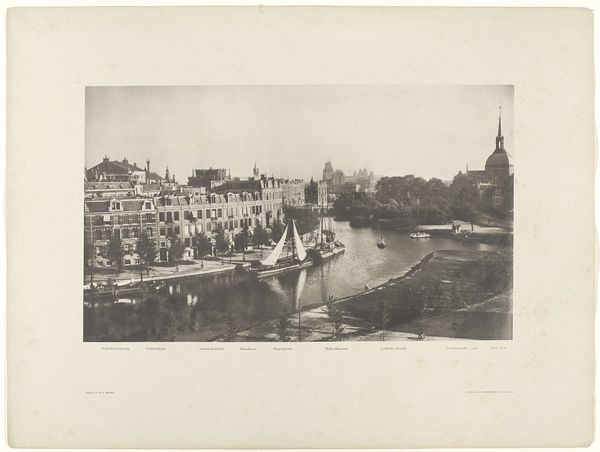

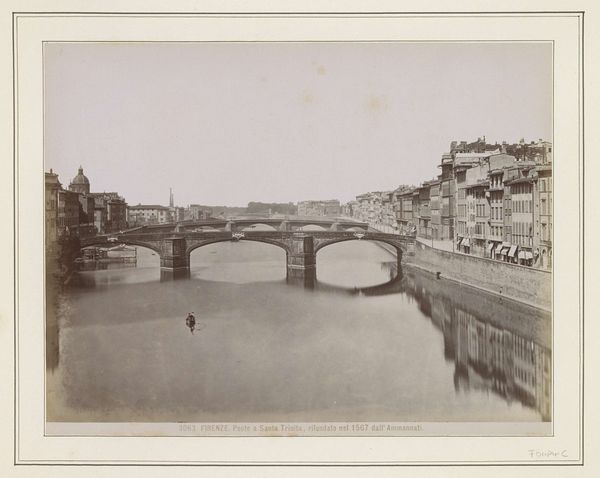

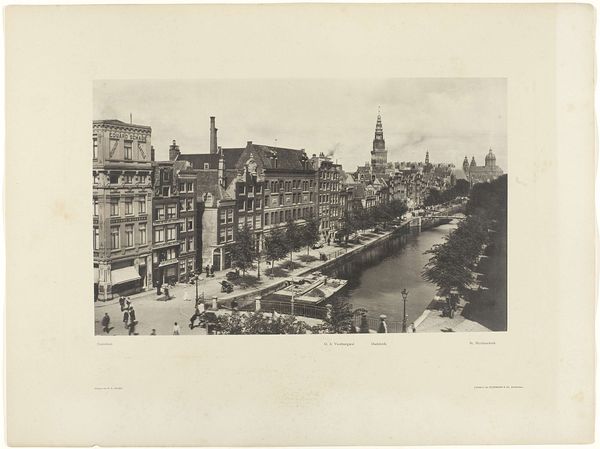

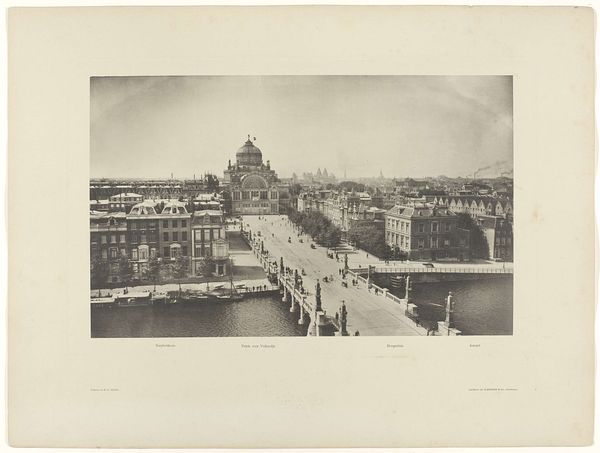

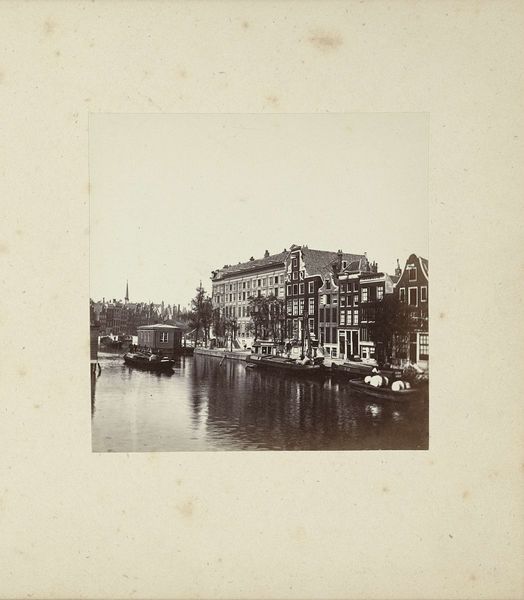

Sarphatistraat and Hoge Sluis, seen from the Paleis voor Volksvlijt; Frederiksplein and Weteringschans, seen from the Paleis voor Volksvlijt; Binnen-Amstel, seen in the direction of the Munt c. 1895 - 1898

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 282 mm, width 465 mm, height 481 mm, width 640 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This photogravure, created around 1895-1898 by Gerrit Hendricus Heinen, depicts a cityscape in Amsterdam, utilizing the gelatin-silver print process. The stillness of the water and the muted tones give it a serene feel, despite being an urban scene. What do you find compelling about this particular print? Curator: The compelling aspect resides within its materiality and production. The gelatin-silver print process, a relatively new technology at the time, democratized image-making. The photograph captures Amsterdam but it's more crucial to think about the labor involved: from the photographer manipulating the camera to the darkroom technicians developing the image. The photographic print, made via mechanization, alters access and distribution from paintings, previously available to elites who could pay for the time, labor, and resources involved in paintings.. What was Heinen commenting on? Editor: I hadn’t considered it in terms of labor, but now that you mention it, it makes me wonder about the accessibility of cityscape views during that period. Was photography challenging traditional landscape painting and its consumption? Curator: Precisely. Traditional landscape paintings required commissions and access to wealthy patrons. Photography, even in its early forms like this photogravure, allowed for wider distribution and a different kind of engagement with urban environments. What societal impact did this new visibility facilitate? Consider the rise of urban planning, civic engagement, and even tourism. Editor: So, it's not just about the *what* – the cityscape – but also the *how* – the mass production and consumption of the image itself that's significant. It’s about a shift in how people see and interact with their environment due to evolving means of production. Curator: Exactly. Thinking about materiality, production and context shifts our understanding of what makes it significant beyond its aesthetics. Editor: Thank you, I'm leaving with a fresh perspective on this print. I won't just consider the scenery in isolation; it will consider labor and dissemination.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

At the dawn of the 20th century, Amsterdam’s rapidly changing face served as the setting for photographer and decorative painter Heinen. With camera at hand, he climbed tall buildings, such as the Paleis voor Volksvlijt (Palace for Art and Industry), which burned down in 1929, and the Rijksmuseum, to take his panoramas.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.