print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

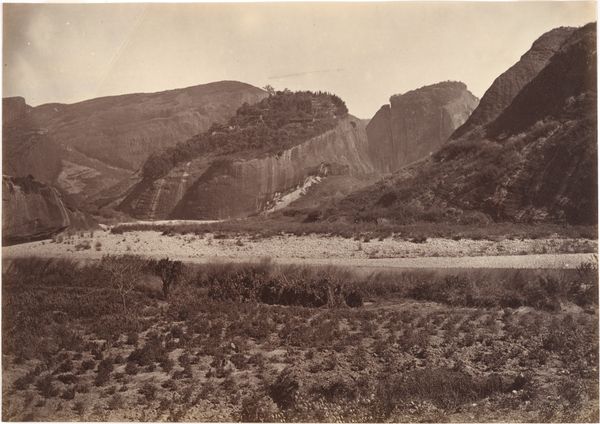

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

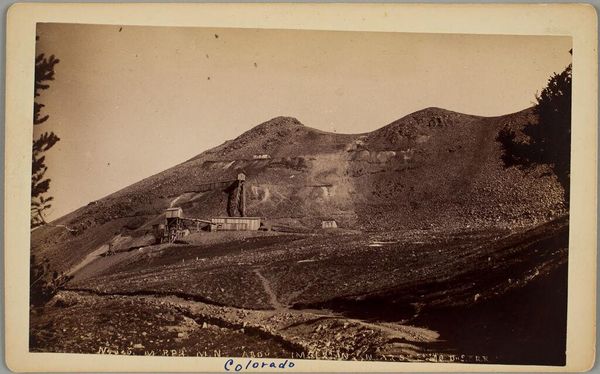

Dimensions: image: 24.3 x 37.62 cm (9 9/16 x 14 13/16 in.) mount: 45.4 x 57.31 cm (17 7/8 x 22 9/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

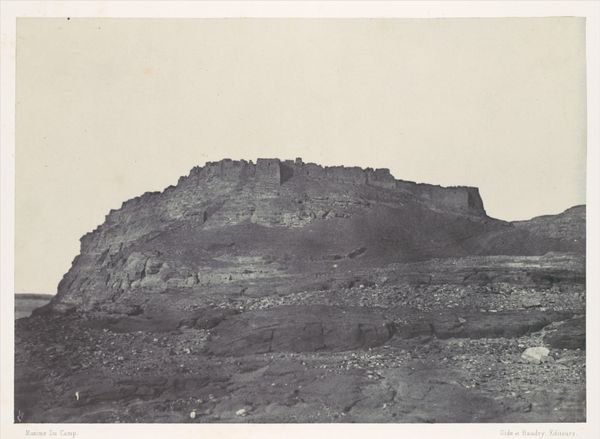

Curator: The sepia tones evoke a sense of looking back in time. What is it that we're seeing exactly? Editor: We’re looking at a landscape, most probably dating to between 1857 and 1858. The photograph is titled "Namculdroog: Droog and Tank," and it’s an albumen print by Linnaeus Tripe. The scale seems quite vast, but subdued at the same time. The horizon is a bit oppressive, making me think of resource extraction, or enforced labor. Curator: It's fascinating how you connect the materiality to those broader themes. As you probably know, Tripe was commissioned by the British East India Company. So, you are not wrong in seeing an oppressive horizon—the photographic process itself was very labor intensive and tied to the colonial project and orientalist imagery, wasn't it? Think about the chemistry, the development process, and the sheer physical labor to get to the finished print! Editor: Precisely! And the orientalist framing here is inescapable. This photograph becomes a tool of documentation, cataloging a landscape ripe for colonial exploitation. It is rendered both monumental and strangely inert under his lens. Curator: It's not just the act of photographing but also the presentation. This was, most likely, part of an album. So think of the collecting, the organizing, and the display of these images for a specific audience back in Britain. What was their intended purpose? Editor: To showcase the "exotic" landscape, to assert dominion and control, and also to stimulate British consumption. But, I wonder, what were the local populations doing as Tripe documented their land? What resistances might have occurred? We never hear these accounts. Curator: A crucial point. The silences and the missing narratives are just as significant as what is presented in the photograph. By viewing Tripe’s image critically, acknowledging its historical and social context, we can start to dismantle those ingrained colonial perspectives and ask, as you have so eloquently done, who is missing from the frame and why? Editor: By really delving into the material and the circumstances of its production, we've given an afterlife to these otherwise static views. Curator: Absolutely, and by analyzing the image in light of postcolonial and materialist readings, perhaps we can give a voice back to that which has been silenced by imperial processes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.