drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

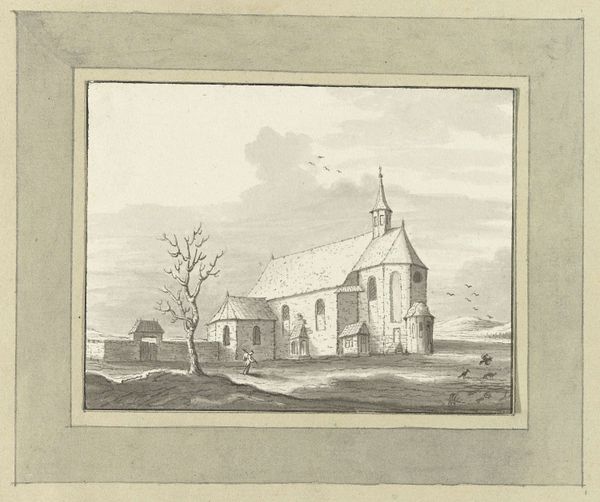

Curator: This etching, simply titled "Kerktoren," or "Church Tower" in Dutch, was created in 1828 by Reinierus Albertus Ludovicus baron van Isendoorn à Blois. It presents a seemingly simple scene. What's your first impression? Editor: It strikes me as serene, almost melancholic. The detail is incredible for an etching – the texture of the thatch roofs, the leaves on the trees. It has an old-world charm, a sort of nostalgic aura. Curator: Etchings like these served as important visual documents of their time, reflecting the changing landscape of the Netherlands. How were these places changing and who did those changes affect? This depiction offers an idyllic scene but the landscape it shows probably meant very different things for people based on socio-economic conditions and how connected to the Church or the ruling class they may or may not have been. Editor: That's a compelling point. Think of the institutional power that church towers symbolized in the early 19th century. They served as visible reminders of both spiritual authority and the societal hierarchy that kept the local clergy in power. Do you believe, considering those realities, that this artwork offers social commentary on 19th century life in Dutch towns, for example the power that the clergy class still held over the masses? Curator: It's a question worth pondering. Perhaps more subtly, it also speaks to the burgeoning Romantic movement that prized emotional and aesthetic experience above pure religious obeisance. I think viewers at that time would feel very different when presented this kind of work compared to a more austere or symbolic work focusing just on religious messaging. The human presence, albeit small, emphasizes daily life, which for some groups might be seen as subversive given traditional messaging about being fully focused on spiritual life, such as monks, nuns, or the extremely religious members of communities at the time. Editor: I agree. It captures a moment in time, holding its place between documentary and evocative scene. The delicate lines almost create a visual memory. The political power of the Church in those times often influenced even the arts, but this work is one where viewers today might have a bit of a dialogue about what it might have meant back then compared to how it presents now. Curator: Ultimately, the etching leaves us contemplating how history, landscape, and identity converge, leaving us space to ponder the nuances of faith, labor, and society. Editor: Indeed. And maybe appreciating how simple scenes can unlock deeper conversations about who wields power and how society is structured.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.