print, etching, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 307 mm (height) x 213 mm (width) (bladmaal)

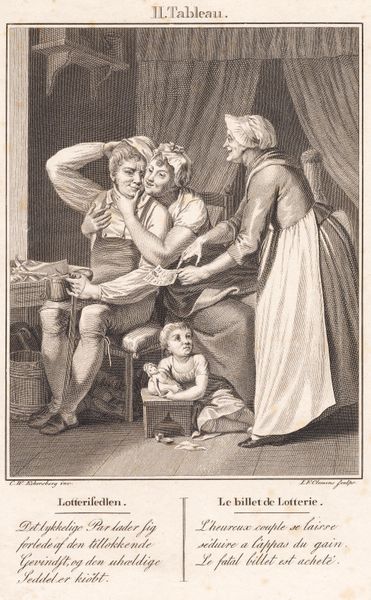

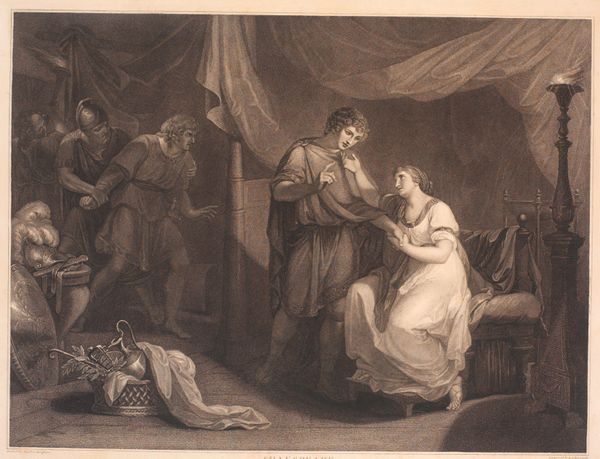

Curator: This print, made circa 1815-1816 by J.F. Clemens and currently held in the collection of the SMK, Statens Museum for Kunst, is titled "Blissful Mediocrity". It's an etching, so what do you make of it? Editor: Well, "mediocrity" seems like a cruel judgement at first glance, doesn't it? There is such despair emanating from that central grouping of figures. Look at the elder woman pointing an accusing finger. The narrative unfolding suggests deep cultural anxieties. Curator: Indeed. Clemens lived during a period of significant social upheaval following the Napoleonic Wars. This affected artistic circles in multiple countries. Prints like this were ways to distribute political messages far beyond where it was produced. The depiction of societal "ills" reflects these concerns, as an explicit warning to the viewers about contemporary morals. Editor: I see the hand-wringing… it's visually present with a figure offering a critique that we can still connect to even two centuries later. Look at the symbolism of the cramped space—the bed barely contained by the edges of the picture plane. This domestic tension creates a claustrophobic emotionality. I'm especially drawn to how her clothing is very obviously disheveled. It isn't overtly sexual, but it is *present*, highlighting shame. Curator: Precisely. The "tableau" style adopted by Clemens places the viewer in the position of a witness, implicating them in the judgement passed on these characters. It's also intriguing to note the text incorporated below the image itself, providing a textual narrative to accompany the visual one, reflecting printmaking as both an accessible and popular medium. Editor: That hand gesture by the accuser dominates everything. But I wonder what Clemens intended regarding her identity, specifically; perhaps the shadow of an elder relative judging one's bad decision? And the almost clinical rendering of her haggard face adds an emotional weight beyond any one individual—it reads as a broader indictment of social morals of the period. Curator: This interplay of private turmoil and public morals makes this seemingly simple engraving a surprisingly dense and fascinating artifact. It prompts us to reflect on our expectations of acceptable social behavior. Editor: It is also quite a sharp commentary about a fear still experienced today about social mores: who dictates propriety, and what are their underlying motives?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.