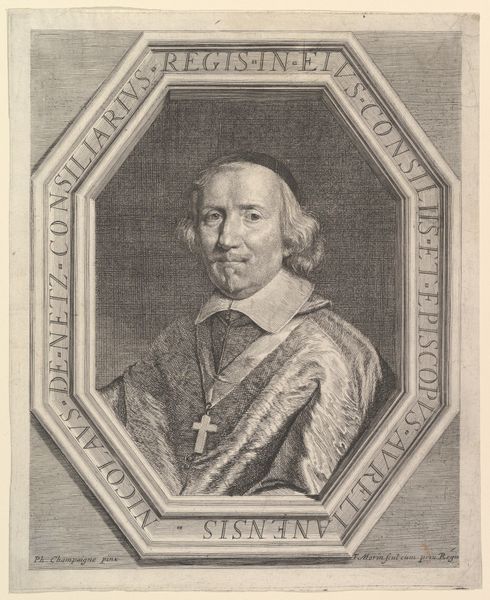

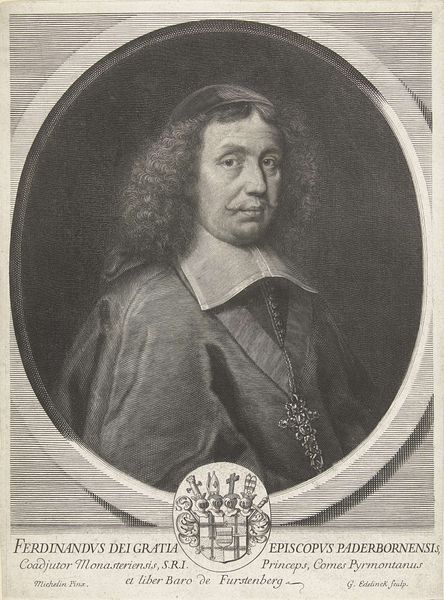

drawing, print

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

Dimensions: Sheet: 17 × 13 1/4 in. (43.2 × 33.6 cm) Plate: 13 1/4 × 11 1/8 in. (33.6 × 28.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This print is a portrait of Hardouin de Beaumont de Péréfixe, Archbishop of Paris, created in 1663 by Robert Nanteuil. It’s currently housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There’s something rather somber about this portrait, a kind of quiet intensity. It’s impressive. And I find myself oddly captivated by the sheer number of individual lines that are employed in the engraving! Curator: Nanteuil was known for his mastery of engraving, particularly in portraiture. His process involved meticulously layering fine lines to create subtle gradations of tone. The paper itself becomes an active participant, its texture interacting with the ink to produce the final image. This elevates the "drawing" or print to another plane. Editor: Right, because in the context of a print, you're always dealing with the reproduction, the dissemination of images to broader audiences, which in turns has implications on societal norms. Also I'd say Nanteuil, in rendering the Archbishop’s vestments and face with such precision, suggests an almost tangible weight to the garments, highlighting social and political significance of attire itself. Curator: Exactly, the material details aren’t mere decoration; they signify status and power. Consider the context of the Baroque era. These elaborate prints were luxury goods in their own right, reflections of the burgeoning consumer culture centered around displaying power. The very act of producing and consuming such imagery reinforces class structure of 17th-century France. Editor: The way his expression is rendered – contemplative, intelligent. There’s an intimate, human element shining through. Even the ornate details surrounding him fail to eclipse that central humanness for me. It’s like, despite all the trappings of power and status, the man himself insists on being seen. Curator: So, for you, it’s about this interplay between the representation of an individual and the societal forces at play during its making. The physical impression on the page bears the marks of both labor and of the cultural landscape within which it was made. Editor: Absolutely. To look at this artwork is like peering into the social matrix of its time, illuminated with such refined artistry. Curator: Yes, Nanteuil provides the image but so many people must have to be involved for its process, and therefore its existence and its presence in front of our eyes. Thank you, let’s move on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.