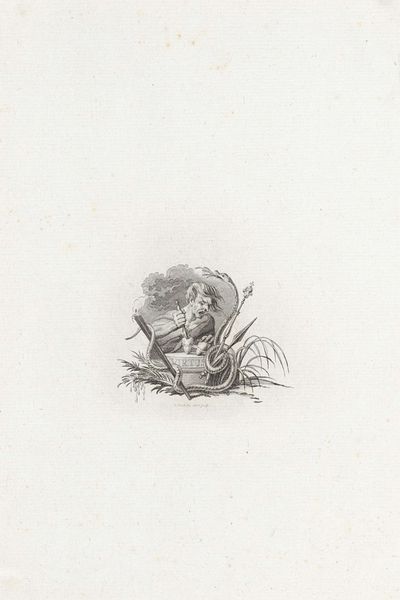

Dimensions: height 226 mm, width 134 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

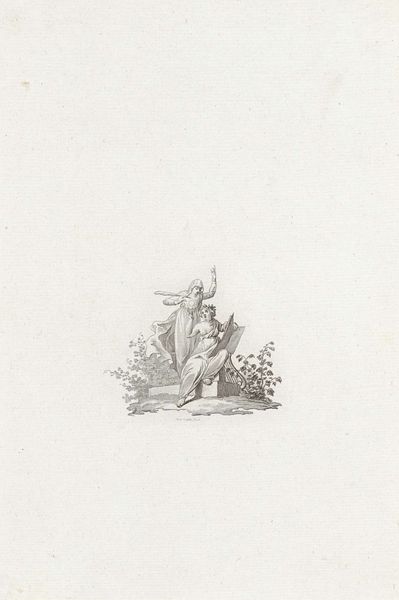

Curator: This engraving, currently held in the Rijksmuseum, is entitled "Vignet met de Dood en een putto" which translates to "Vignette with Death and a Putto", crafted between 1751 and 1816 by Reinier Vinkeles. The contrast is immediate, isn’t it? A stark black and white composition. Editor: Indeed. Death and a putto... quite the juxtaposition. I'm immediately struck by the technical skill though. The clean, precise lines of the engraving give it such a delicate, ethereal quality. The texture created, almost a velvety smoothness juxtaposed with jagged skeletal details. The paper itself becomes part of the art. How would it have felt to create this, tool in hand, the careful control over material? Curator: Let's dive into the imagery. We have a skeletal figure of Death, seemingly emerging from a cloud, offering a laurel branch – a symbol of victory or peace. And then the putto, representing innocence and life, reaching out. The tension here speaks volumes. What could this imagery mean? The putto touching death? Editor: To me, that skeletal form offering a branch becomes interesting when thought of alongside others that made prints like this. It begs questions around workshop production methods. Is this paper the best choice? Who would have bought and consumed this? The final price point matters hugely when you understand this sort of work! And, while you see the imagery and consider innocence meeting death, I am more preoccupied with how this was consumed materially, daily, within the walls of its new home. Curator: Ah, yes, and that would affect its cultural reading. The putto is such a prominent figure in baroque art. It is frequently linked with religious concepts of life and love. Could this image then, represent hope emerging, even in the face of mortality? The skeleton offering the branch instead of striking, almost seems merciful. Or maybe that death is but a path into rebirth? Editor: Or maybe the availability of paper and ink drove these images? Perhaps the material constraints – the limitations of engraving – drove the simplicity and created opportunity for sales and distribution of this art as object, not just as ideal? I feel so connected to its construction by viewing art this way! Curator: I find it intriguing how you can consider material first while, for me, the human narrative, told through symbolic languages that developed over millennia, comes so forcefully into view. Ultimately, it seems we are looking at the very definition of the fleetingness of life and the endurance of symbolic image itself in a world of material transience. Editor: Precisely. By considering its creation we are able to have a material understanding and see that fleeting moment still preserved thanks to material existence, long after Vinkeles' hands last touched the paper.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.