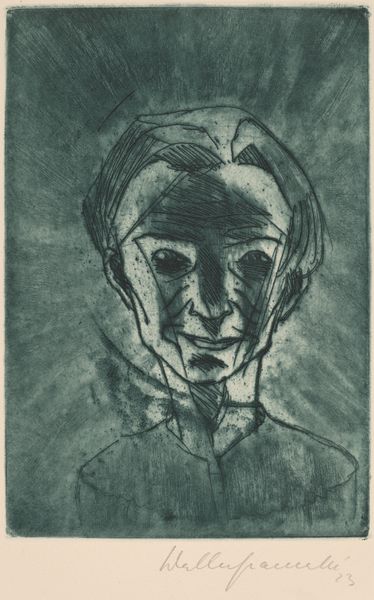

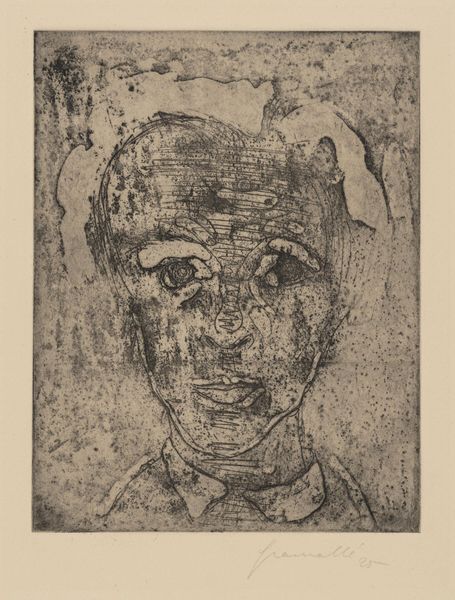

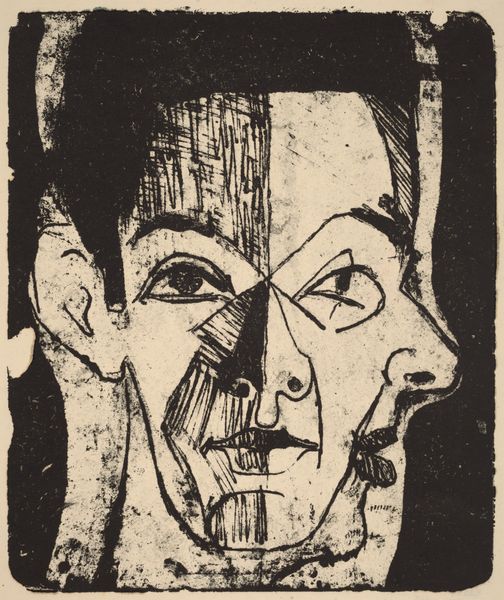

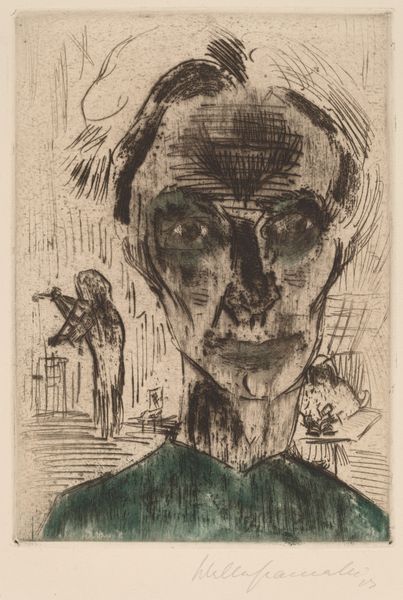

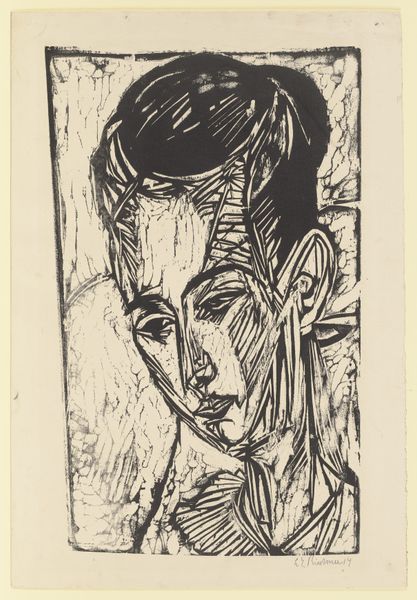

Bust of a Young Man, Self-portrait (Knabenkopf, Selbstporträt) 1922 - 1923

0:00

0:00

print, etching

#

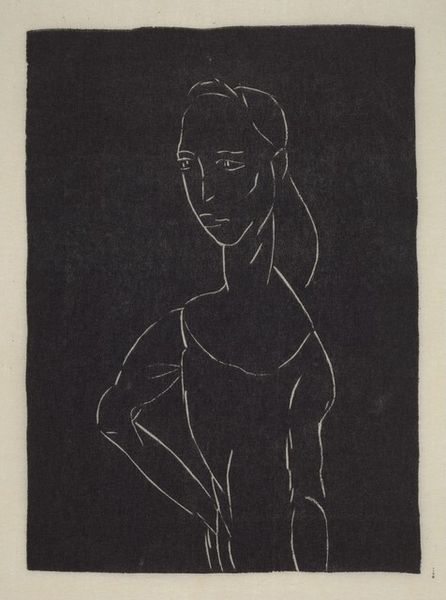

portrait

#

self-portrait

# print

#

etching

#

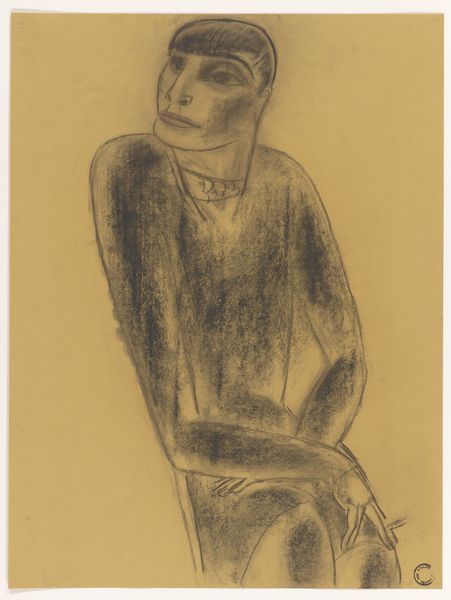

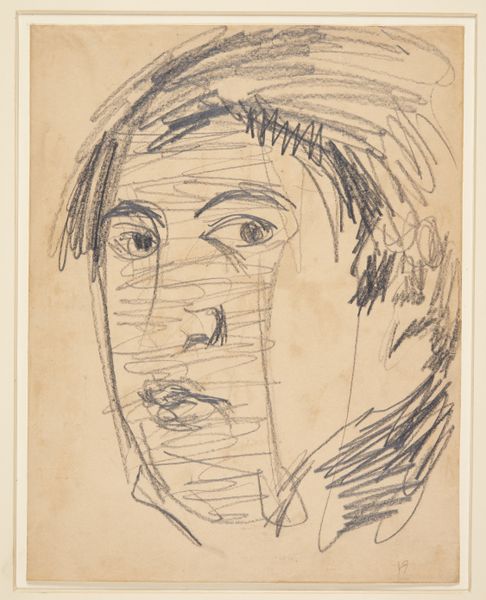

pencil sketch

#

german-expressionism

#

pencil drawing

#

expressionism

Dimensions: sheet: 52.8 × 36.5 cm (20 13/16 × 14 3/8 in.) plate: 32.5 × 24.5 cm (12 13/16 × 9 5/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

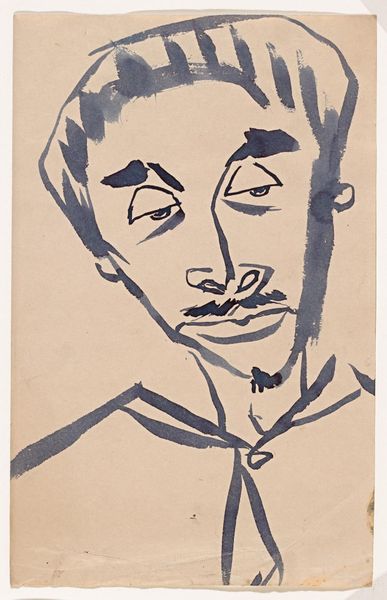

Curator: Here we have Walter Gramatté's "Bust of a Young Man, Self-portrait," created between 1922 and 1923. It's an etching, falling within the German Expressionist movement. Editor: It’s really striking. The texture created by the etching process lends the face an almost weathered, anxious quality, doesn't it? It's quite raw. Curator: Absolutely. The expressive lines contribute heavily to the emotional impact. Etching as a printmaking technique democratized image production during the early 20th century. I am interested in the scale of Gramatté's edition size and the implications of making his own likeness broadly available in postwar Germany. Editor: That’s fascinating. For me, I immediately think about the tradition of self-portraiture, and how Gramatté engages with it in this piece. You see echoes of it through art history as an instrument for self-expression and presentation. But Gramatte seems to be after something deeper here, doesn't he? Curator: Yes, consider the societal context. Expressionism, especially in post-war Germany, reflects profound psychological disruption. His choice to create this piece as a print suggests wider distribution, creating multiple originals cheaply—which I'm certain were circulated through avant-garde, more underground art channels than exhibited in a museum. Editor: How would his self-image resonate with audiences then? The intense gaze, the exaggerated lines, it speaks of vulnerability, yet also defiance, maybe of disillusionment too. Curator: Possibly, that depends upon the political leanings of the individuals who collected it. This piece is more complicated in terms of reception because its distribution wasn't determined or managed by any singular political party. But again, he is reflecting broader societal anxieties—but through the specific process of a readily available art form that bypasses established hierarchies. Editor: Thinking about art making itself. Do you feel that printmaking contributed in any specific way to the ethos of Expressionism? I’d suggest, this form enabled artists like Gramatté to communicate those challenging and provocative perspectives to new, perhaps disenfranchised, audiences at that moment in history. Curator: Definitely. It made art accessible beyond elite circles, allowing for potent political or emotional statements to be disseminated more widely. And here Gramatté is depicting himself, both subject and maker aligned in a single striking image. Editor: It's a small, but deeply resonant window into a turbulent era through a unique set of material processes, cultural mores and political urgencies. Curator: Exactly, a convergence that gives the work lasting power for those looking for an access point into understanding a historically critical moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.