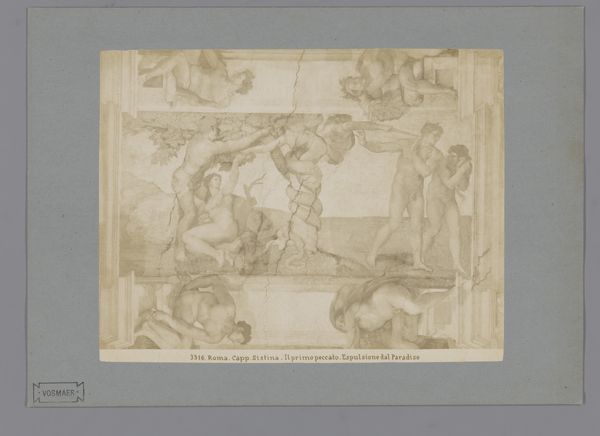

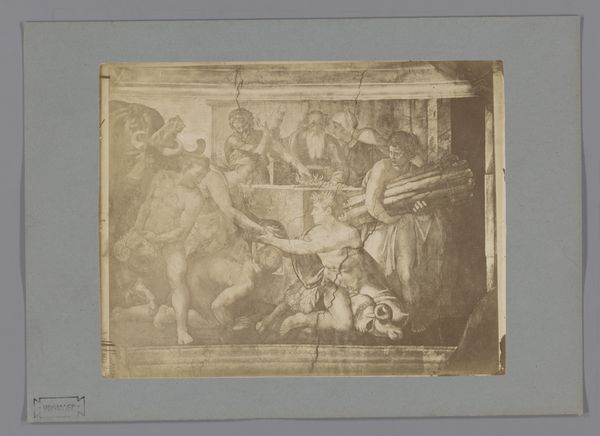

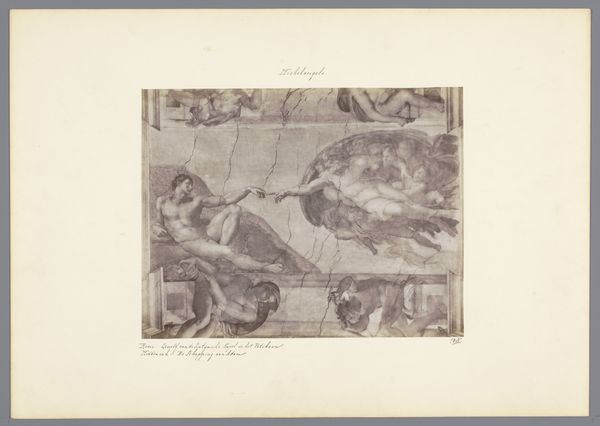

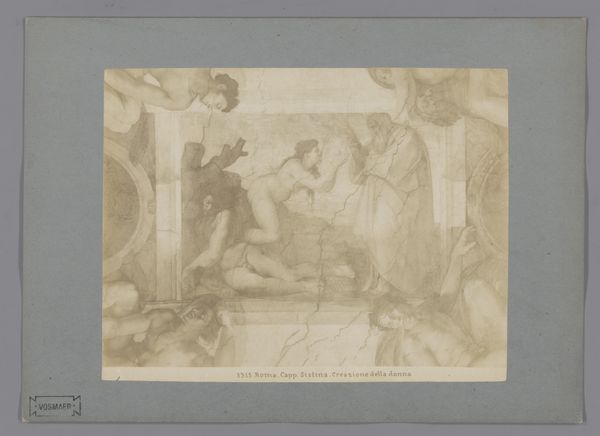

Fotoreproductie van het fresco De schepping van de wereld door Michelangelo in de Sixtijnse kapel 1851 - 1900

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, fresco, photography

#

high-renaissance

# print

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

photography

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: height 202 mm, width 258 mm, height 259 mm, width 356 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, created sometime between 1851 and 1900, offers us a photographic reproduction of Michelangelo’s fresco, *The Creation of the World*, found on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. It's held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a spectral quality. Seeing such an iconic image drained of its vibrant color almost imbues it with an even greater sense of history and… weight. There is a deep sense of the past conveyed here. Curator: Indeed. Think about the social implications. By the latter half of the 19th century, photography allowed wider audiences than ever before to engage with grand artworks that were previously only accessible to those who could visit places like the Vatican. The proliferation of images like this democratized access, of sorts, to High Renaissance ideals and artistic accomplishment. Editor: It does more than just democratize; it refracts the symbolic power. The figures of God and Adam, those representations of ultimate creator and created being are now mediated. Does the mechanical reproduction alter our understanding of the original moment, charged with the fervor of the Renaissance papacy? Curator: Well, that’s debatable. Consider that the Sistine Chapel itself was as much about papal power as it was about divine inspiration. Michelangelo was working for the Vatican, and the chapel served as a stage for displaying that power. Photography in this sense, became another method—an echo, if you will—of diffusing cultural prestige, albeit through a different technological channel. Editor: It's a dilution and a preservation at once. What’s interesting is how the image holds its narrative power even when divorced from its original medium. God's reaching finger continues to carry the symbolic weight of potential, of divine intervention, across centuries and technologies. Curator: Precisely. Despite the changed medium, academic art of the time leaned heavily on the Renaissance as a historical source of truth and beauty, making photographic reproductions such as these valued resources for disseminating particular aesthetic and even ideological values throughout society. Editor: Yes, this work then functions almost like a visual echo of artistic and religious symbolism, carrying whispers of both Michelangelo’s artistic genius and the Church’s cultural power, transformed through a lens of history. Curator: Ultimately, looking at this photo helps me reconsider how cultural and political capital travels and transforms across time. Editor: And for me, how even faded, mediated symbols retain their resonance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.