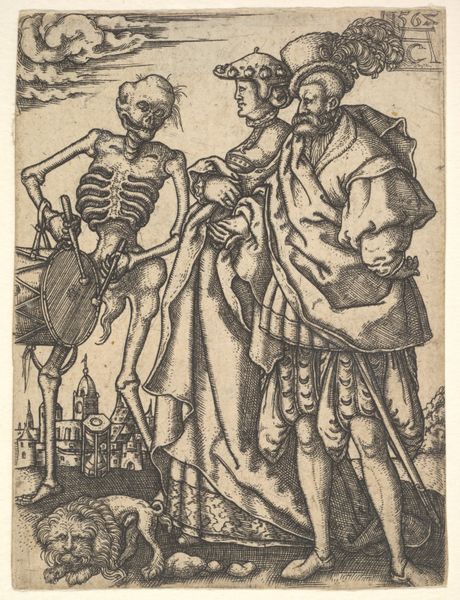

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

allegory

# print

#

death

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 6 1/8 × 8 3/4 in. (15.5 × 22.3 cm) Sheet: 6 5/16 × 8 15/16 in. (16 × 22.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Death and the Devil Surprising Two Women," was created by Daniel Hopfer sometime between 1510 and 1520. It’s currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: The cross-hatching alone creates an oppressive weight, doesn’t it? And the composition, with the skeletal figure of Death looming… the whole thing just feels steeped in anxiety. Curator: These depictions of Death as an active figure were popular visual metaphors during the late medieval and early Renaissance periods, reminding people of their mortality in a society gripped by anxieties regarding salvation, plagues and social hierarchies. Notice Death's attire--those flimsy cloths. Editor: Right. And the way Death’s holding that hourglass and skull! He's really leaning into the allegorical symbolism there, isn't he? I'm drawn to how this print uses material to its full potential: that stark contrast emphasizes the temporality of flesh versus the lasting qualities—however morbid—of metal. Curator: The inclusion of the devil is fascinating because it pulls into a broader religious discourse present within 16th century Germanic areas— particularly concerning faith versus evil. Daniel Hopfer adapted the era’s fascination into visually stunning metal works, which allowed for wider consumption amongst the emerging merchant class. Editor: These two fashionable ladies are caught totally off guard as their reflections are scrutinized with material vanities represented in a mirror… it does feel inherently gendered when viewed from a contemporary perspective. What did it mean in this context for women to become such obvious visual subjects and consumers of such objects? Curator: Excellent question. Representations like these in Northern Renaissance art were often directed at women to teach how they might actively participate within Christian spiritualism while existing as objects and property. Editor: So the material of this engraving became almost… didactic. It circulated in specific networks with messages baked right into the lines and forms. How clever! The visual power translates across centuries. Curator: Precisely! Thank you. Understanding its creation opens up broader insight within social narratives of the era and continues our work around accessibility. Editor: And recognizing the material conditions makes those narratives all the more poignant and, sadly, more relevant today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.