print, intaglio, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 244 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

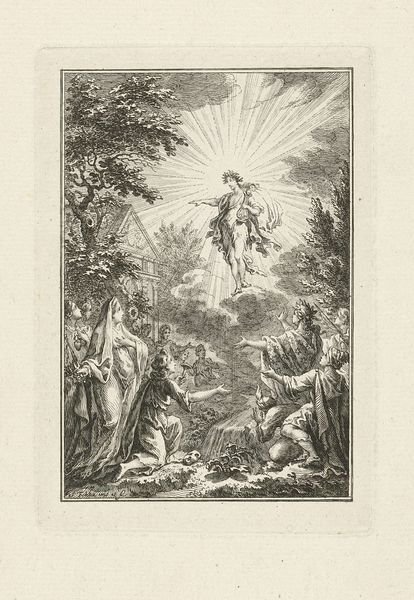

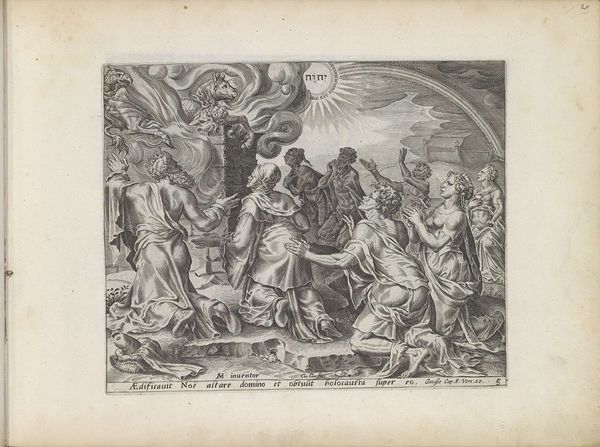

Curator: This intaglio print, entitled "Doop van Christus", or "Baptism of Christ", is attributed to Crispijn van de Passe the Younger, dating from sometime between 1604 and 1670. Editor: My immediate thought is, wow, what a striking use of light and shadow. The dove descending seems to emit such intense brightness, contrasted against the detailed, almost somber landscape. The figures appear captured in a pivotal moment. Curator: Yes, it really highlights a classic baroque characteristic, evoking drama. Notice how the engraver uses light to represent divine intervention and power. We can think of the cultural history in which, after the Council of Trent, artists turned increasingly to didactic, rather emphatic and explicit forms of Catholic image production. Editor: Considering the history, where do you see the impact of, say, sociopolitical context within the image itself? For instance, what statements are being made about identity and authority in the positioning of John the Baptist versus Christ? Curator: Interesting point! Note John’s robust and active pose, against the bowed, almost submissive position of Jesus. It can suggest, to contemporary eyes, complex interactions with religious dogma around salvation versus worldly authority in representations of the Holy Trinity. There's almost a dialogue happening about the Church's power relative to faith. Editor: Indeed. The depiction of the angels, especially with their positioning—gazing rather forlornly on what appears to be some kind of landscape in the back, adds a layer of societal expectation and performativity, particularly around notions of faith. The almost documentarian style foregrounds the religious act within an intricate earthly sphere. Curator: Looking at it from a broader lens, these prints, these accessible artworks disseminated to a broader audience than commissioned painting cycles for the elite, become significant historical artifacts showing us shifts in social, cultural, and artistic currents of the 17th century. Editor: Right. And in thinking of its dissemination to a broad audience, what stories did this print invite, how were certain power relations cemented or challenged in individual, or local communities, by its public consumption? Many avenues open up! Curator: Agreed. Each of those narratives tells another story of cultural production and societal reception—and of power, of course.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.