Dimensions: height 142 mm, width 157 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

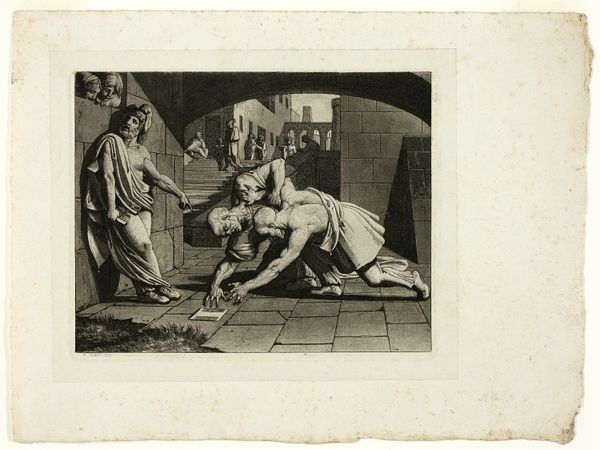

Curator: I’m immediately struck by the vulnerability of the figure kneeling before the father. It speaks to themes of repentance and forgiveness, doesn’t it? Editor: Absolutely. We're looking at "Return of the Prodigal Son" by Adam von Bartsch, created around 1795. It’s an etching, and the piece is housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Beyond the raw emotion, what fascinates me is the staging – the architectural elements creating this sense of intimacy despite being outdoors. Curator: I agree, that staging adds another layer. The older son, standing off to the side, his face etched with perhaps resentment, is pivotal to understanding this image through today’s lenses. We see how patriarchal structures perpetuate narratives of exclusion. Why does one son earn grace while the other is relegated to the margins? It prompts a broader discussion about privilege and the arbitrary nature of forgiveness in society. Editor: Interesting take. My sense is more focused on the historical interpretations. The image, steeped in Baroque aesthetics with that intense contrast, speaks to a period grappling with moral tales, viewed from a cultural history perspective. It highlights how art disseminated religious stories, shaping societal values of the time through the lens of morality and family dynamics. Curator: Yes, and thinking about dissemination, the medium of print is vital here. How does this specific technique democratize access to these stories? Further, what is the relationship between the artist's life and the image of brokenness so effectively captured? It may point toward the universal themes of marginalization. Editor: That last aspect you mention, thinking of universal stories in light of religious dissemination via prints, gives another perspective, yes. We’re pushed beyond the immediate Biblical context, nudging the artwork towards deeper exploration that remains significant. Curator: It is in exploring and discussing interpretations like these, from socio-historical standpoints, that a viewer’s engagement may hopefully extend beyond surface appearances into more meaningful territory. Editor: I concur entirely. That push and pull between historical document and contemporary conversation is essential for us, as interpreters.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.