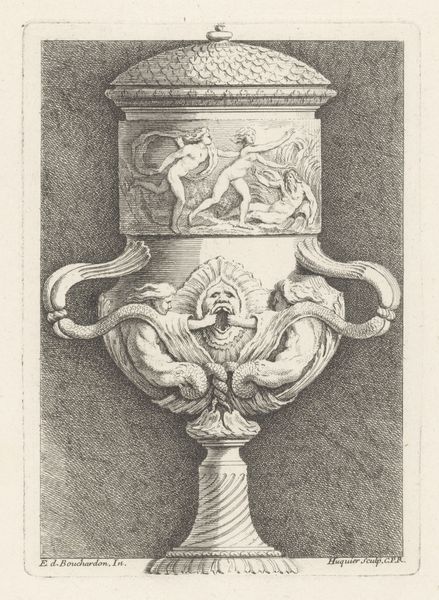

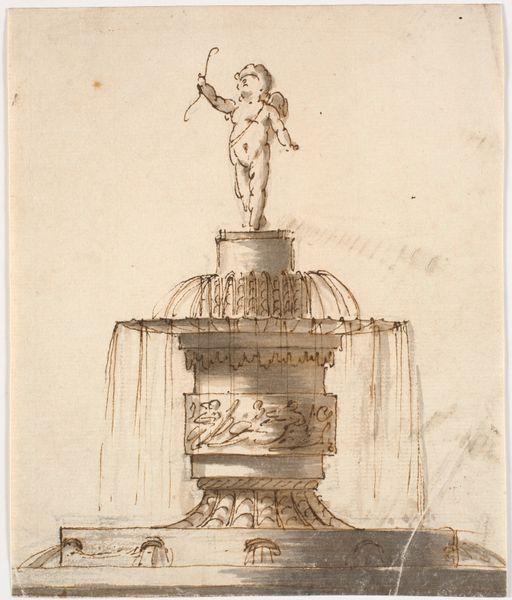

print, sculpture, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

sculpture

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 199 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this engraving entitled "Vaasvormige Fontein," or Vase-Shaped Fountain, made between 1729 and 1737. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. The artist was Gabriel Huquier after F.D. Bouchardon. Editor: It immediately strikes me as a bit grotesque, in an almost charming way. The squatting figure at the top especially. It gives the piece an odd, animated feel despite the static medium. Curator: The baroque loved these dramatic contrasts. The figure you're referring to, perched atop the fountain, speaks to the era’s fascination with the mythical and the theatrical. Remember that prints like these allowed the latest fashions in garden design to circulate widely among the aristocracy. Editor: Yes, but that squatting figure looks like some ancient forest deity…or perhaps even a Silenus, a companion of Dionysus. There is a bestial quality about him with an implicit connection to primal forces. Water, fertility...life. What’s particularly interesting is the face contorted as though it is yelling to no avail! Curator: Interesting observation! Water features were vital demonstrations of wealth and technological prowess within the noble parks and gardens. Fountains signaled dominance over nature. The imagery often underscored the patron's power, echoing classical themes to legitimize their position. The 'Privilege du Roy', indicated on the engraving here, essentially provided the artist with copyright protection granted by the king. Editor: I'm drawn to the faces embedded in the fountain's base. Are those satyrs? Are they further expressions of this Dionysian energy, echoing through water, stone, and our peculiar forest figure? It’s as if the fountain itself is a living entity. It appears in a liminal state between organicism and classicism Curator: The artist employs hatching and cross-hatching to render texture, bringing depth to a static work and emphasizing its ornamental complexity. These weren't merely representations of sculptures; they were tools of aspiration and dissemination. It's the eighteenth-century version of an architectural digest! Editor: Yes. Seeing how symbols can carry meaning over such expanses of time always fascinates me! That sense of memory, distilled through such forms. Thank you. Curator: Indeed. Understanding these visual emblems grants us insights into a long and fascinating discourse concerning taste and social order.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.