sculpture, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

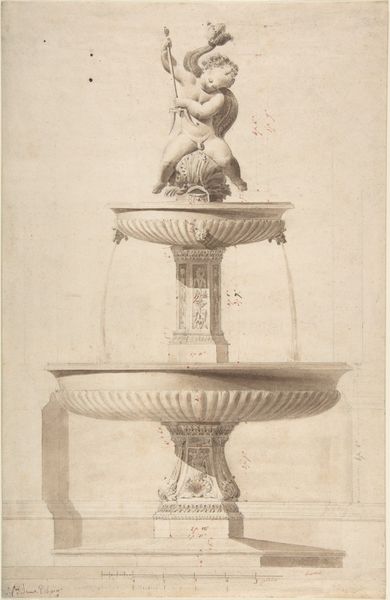

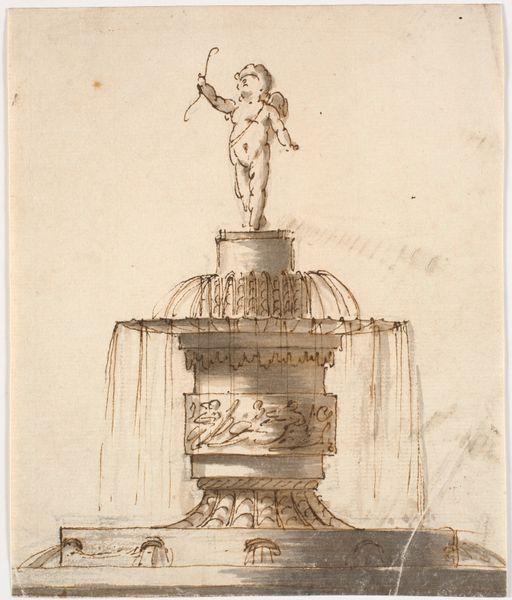

Curator: Here we have a depiction of a fountain, “Fontein met jonge Bacchus op rots,” created between 1680 and 1707 by an anonymous artist. It's an engraving, offering us a detailed view of the sculpture. What strikes you most about it? Editor: Initially, I'm captivated by the rendering of textures. Look at the contrast—the smooth skin of Bacchus against the jagged rock. The starkness really pulls the eye, even with the limitations inherent to engraving. It makes you consider the work that went into recreating stone, water and flesh through ink. Curator: Absolutely, the detail is remarkable. The image also offers insights into the artistic and social values of the Baroque period. Allegorical depictions were very popular and so was a fascination with classical mythology, which served the cultural elite. What kind of role do you think artworks like this one served? Editor: Certainly. These weren’t just aesthetic pieces, were they? There’s the function, which in this case is literal: the rendering of a water system. But, even in its artistic depiction, we see something practical. There's a consideration of materials that moves beyond surface and delves into social positioning via displays of wealth. Curator: Precisely. This era was also shaped by powerful forces. Art became increasingly involved with displays of power through commissions by both Church and aristocracy who understood its propaganda and visibility value, both political and social. Editor: Considering all of these societal considerations—do you find something lacking, something the limitations of engraving itself can not fully recapture? Curator: Possibly its tactile presence. The engraving flattens it, loses the three-dimensionality and subtle nuances in the surface of the sculpted rock. Yet, what we gain is broader distribution—transforming what might be a garden piece for the few into a study piece for many. Editor: So it goes from unique luxury good to something closer to accessible knowledge—interesting considering all of the hands it must have passed through to create this image through engraving methods. A copy of a copy. Still it raises questions of authorship, the labour of artistic production, and social worth of this imagery—ideas still potent today. Curator: Indeed. Looking at the cultural value, from garden centerpiece to an image distributed to and appreciated by a much wider public through prints is valuable. It opens up many discussions about the transformation and democratization of art. Editor: A fascinating piece—shifting the dialogue of social impact and labor. I'll look at engravings a bit differently after this!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.