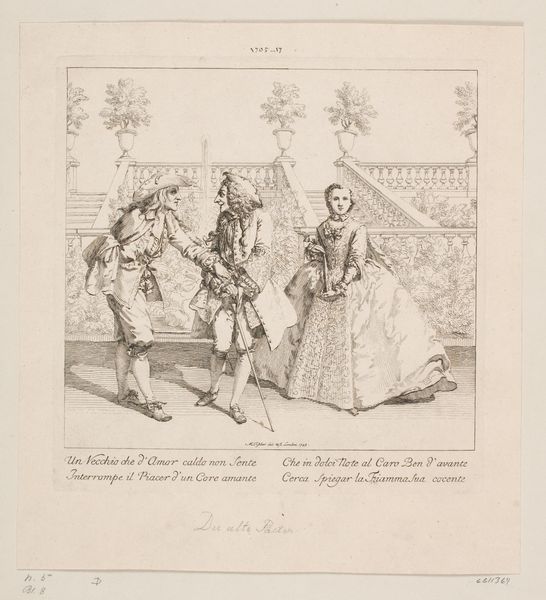

Piekenier, grenadier en rijke man en vrouw in kleding uit de zeventiende eeuw 1857

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 149 mm, width 233 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This drawing on display comes from the Rijksmuseum’s collection. Produced in 1857, this engraving is called "Piekenier, grenadier en rijke man en vrouw in kleding uit de zeventiende eeuw," or "Pikeman, grenadier, and rich man and woman in seventeenth-century clothing." It's attributed to an anonymous artist. What's your initial read on this, considering its visual storytelling? Editor: My first impression is one of studied distance. Despite sharing the same picture plane, the figures don't quite connect. They seem more like actors in a historical tableau, carefully arranged yet emotionally detached. Curator: Indeed, that echoes a very conscious engagement with symbols and archetypes of status and occupation. We're given a glimpse into societal roles and their visual markers: the pikeman and grenadier representing military might and the well-to-do couple embodying wealth and leisure. It reads as a memory of a certain era. How do you interpret this from a historical viewpoint? Editor: The image highlights the romanticized gaze of the 19th century upon the 17th. It tells us as much about the values of the 1850s—fascination with class structure and military prowess—as it does about the actual lives of people in the Baroque period. It speaks to the socio-political climate of the time and how they wanted to see themselves in relation to their predecessors. Curator: That's a key point about memory shaping how we look at history! Observe how each figure bears the symbolic weight of their role, carefully emphasized through their garments and poses. How does the artist create visual distance through attire, especially concerning power dynamics? Editor: I see it particularly in the stiff formality of the wealthy couple juxtaposed with the more dynamic, engaged stances of the soldiers. This contrast creates a subtle but effective hierarchy, reflecting the social stratification that was both admired and, increasingly, challenged during the 19th century. Curator: It suggests a world carefully structured around symbolic representations. A past re-imagined through the visual language of hierarchy and display. Editor: Absolutely. An engagement not so much with historical reality but rather with its curated image. Food for thought on the public role of art itself! Curator: Yes, a very pertinent insight as we try to trace visual continuities across time, and our interaction with the cultural markers around us. Editor: It really underscores how the past is not a fixed entity but rather something that's continuously reinterpreted through the lens of the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.