drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

coloured pencil

#

group-portraits

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

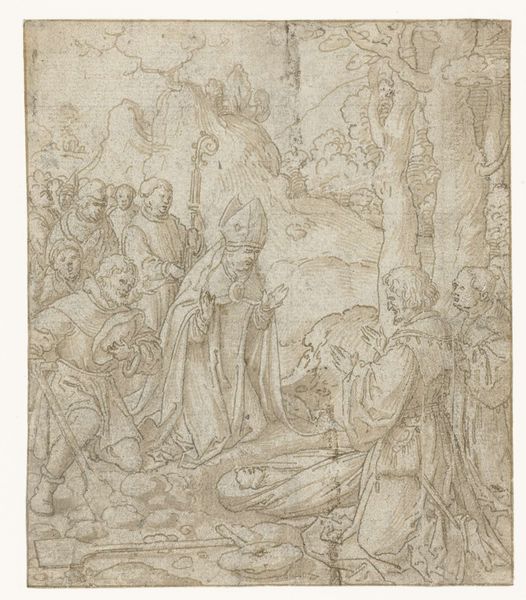

Curator: Looking at this somber piece by Willem Pietersz. Buytewech, created around 1619 and titled “Terechtstelling van de baljuw,” or “Execution of the Bailiff," now housed at the Rijksmuseum. It certainly leaves an impression, doesn't it? Editor: Indeed. My immediate reaction is one of chilling austerity. The monochromatic palette, the stark lines… It amplifies the gravity of the scene unfolding. Curator: As a historical artwork, it’s vital to consider the broader socio-political backdrop of the Dutch Golden Age. Public executions like this were a grim spectacle, but also a display of authority and legal process, crucial for maintaining social order. The setting and even the clothing choices tell us about this purpose and about its specific position. Editor: Exactly, I am captivated by how Buytewech stages power. The central judge’s commanding hand gesture contrasts with the bailiff kneeling, head bowed. We can look at how the very construction of gendered power informs the work: male gazes, positions of supplication and those of power are contrasted directly against one another to make a distinct point. Curator: And consider the subtle yet forceful presence of the crucifixion scene above the judge. The juxtaposition of earthly justice and divine judgment, the relationship between law and religion during that era. The history painting provides the perspective and authority of divine forces looking on, witnessing this supposed righteous act. Editor: From a contemporary lens, I can’t help but see the potential for abuse in such a system. The ease with which power can be wielded against individuals and specific populations and demographics under the banner of “justice” raises critical questions about institutional accountability then as well as today. Who had the power? Who was systemically represented and underrepresented at the time? Curator: That's a salient point and looking at art from this era also is recognizing some problematic elements, from the limited view to questions about the violence enacted against many in those times. It does force us to reevaluate. Editor: Absolutely. Analyzing historical art necessitates that kind of intersectional understanding, revealing how these scenes resonated then, and perhaps should unsettle us now. These visual texts, these stories that are retold, must encourage critical conversations and prompt more reflection. Curator: A powerful reminder that engaging with historical art demands not just admiration, but careful consideration of the historical framework. It gives more to see the old from this new context. Editor: Indeed, engaging in artwork with an ever critical understanding will allow a better opportunity for social change and representation. It gives voice.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.