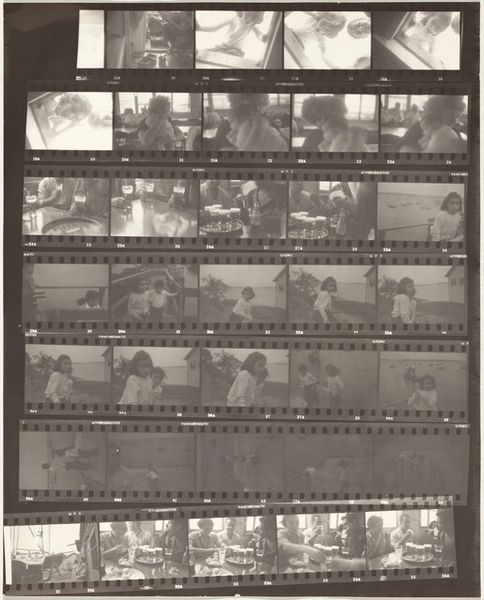

Dimensions: sheet: 25.2 x 20.3 cm (9 15/16 x 8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

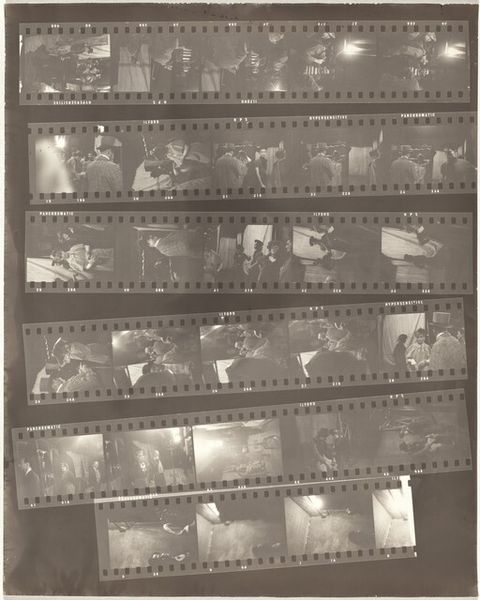

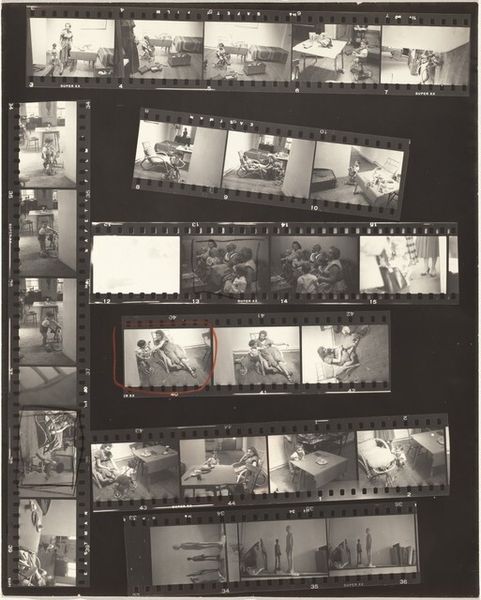

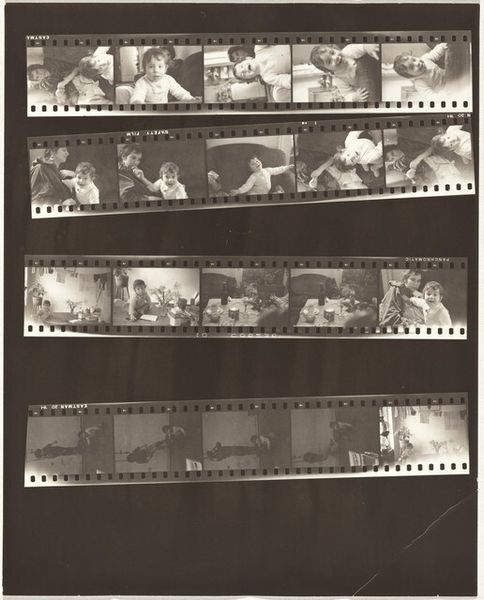

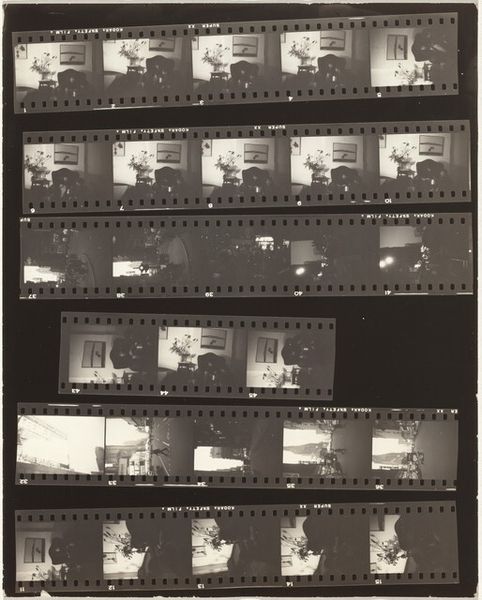

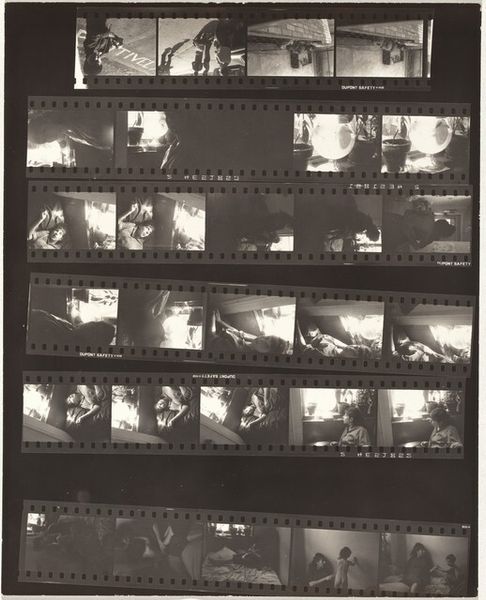

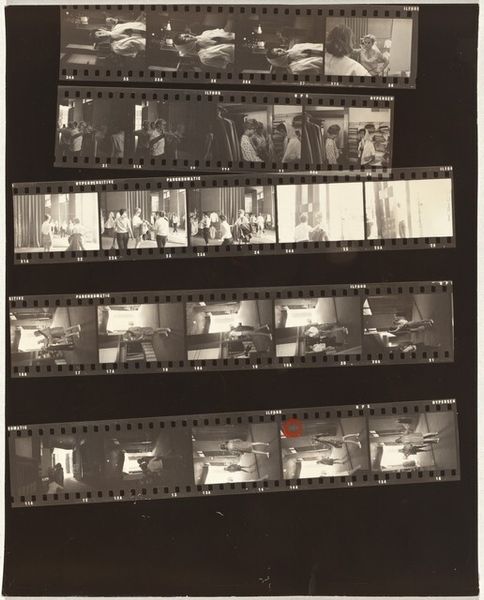

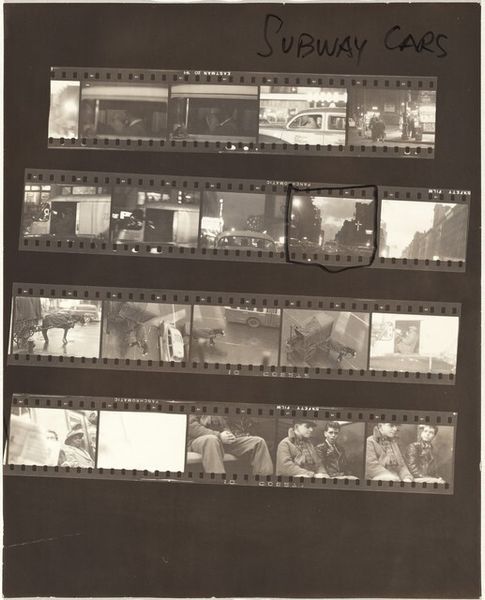

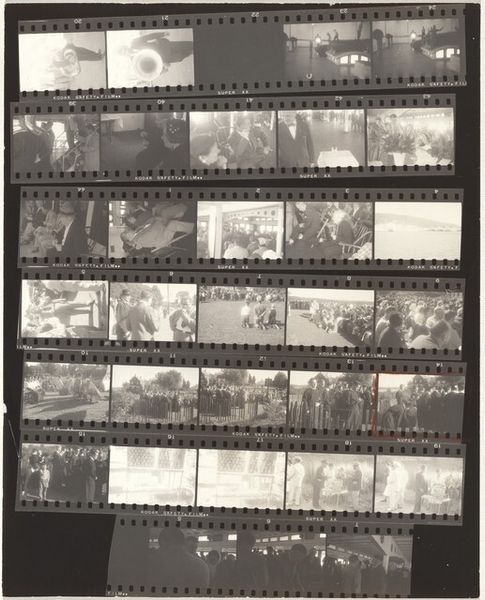

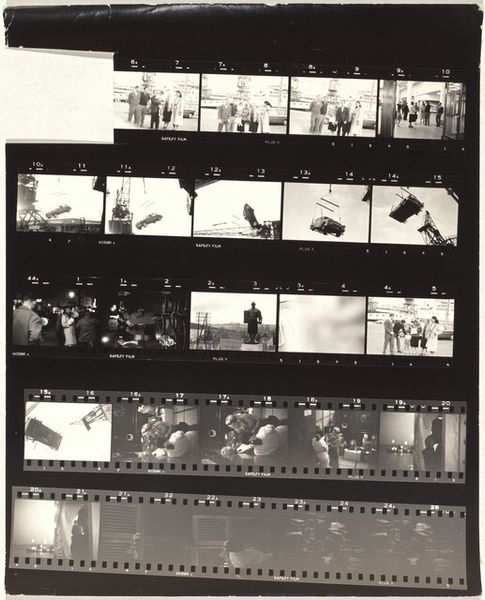

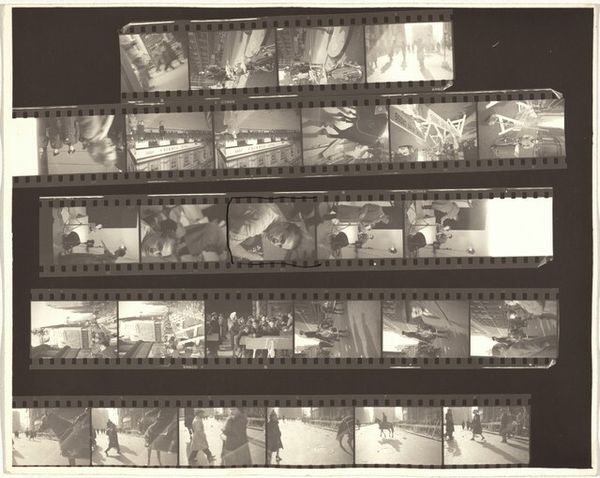

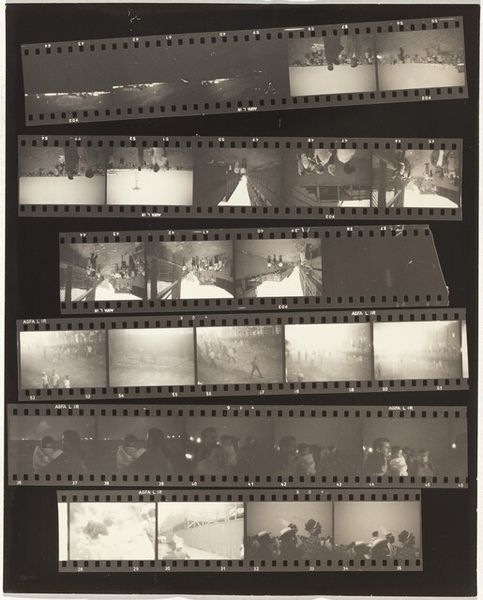

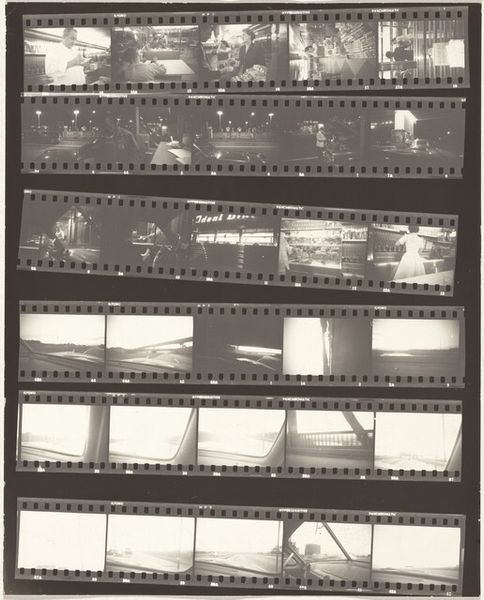

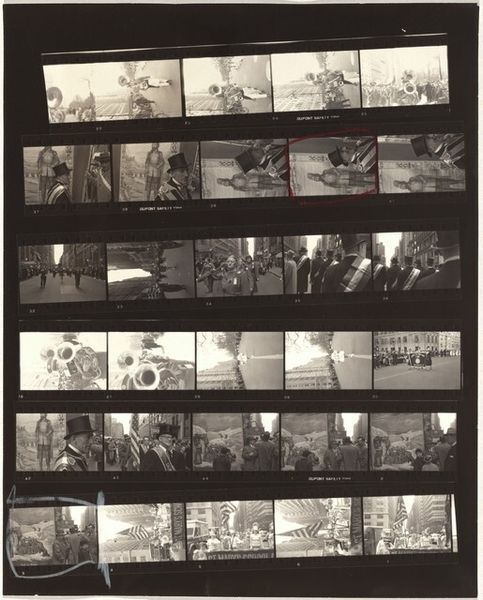

Curator: Here we have Robert Frank's "Pablo and Karen, Halloween--New York City no number" taken in 1954. It's a gelatin silver print, part of his photographic essay on American life. What strikes you first about this piece? Editor: Well, visually it's immediately striking – the starkness, the graininess. It's raw, like a snatched memory rather than a carefully composed portrait. There's an almost dreamlike quality to the presentation too. It makes me wonder about that 1954 Halloween, New York—it's an everydayness elevated with emotion, isn’t it? Curator: Precisely. Frank wasn’t interested in glossy depictions of American prosperity. Instead, he pointed his lens at the unvarnished reality of postwar America – the marginalized, the overlooked. You sense that honesty in his portraits. He documented outside the narrative everyone else was creating. Editor: Absolutely. You see this contact sheet almost as a behind-the-scenes of his selection process; like a collection of fleeting stories begging to be pieced together. And those deep shadows... they add an ambiguity, right? This makes it feel like it reflects a feeling or experience instead of showing the thing itself, it could be anyone's feeling or experience from that period. It's strangely universal in that way. Curator: It’s what makes his work so compelling. Frank disrupted conventional photography. He embraced imperfection. That looser aesthetic made it harder to display in public because many found it lacking any aesthetic interest, but eventually allowed the medium to mirror more personal, subjective experiences, and ultimately pushed photography towards something truer to lived experience. Editor: I feel as though looking at this contact sheet is like reading someone else’s journal. It really pushes me to consider that what we think of as art are also decisions and process. A selection from so much material. Curator: That's wonderfully put. Frank’s art isn't about perfect composition, it is a visceral expression. It resonates because he made a point of reflecting our shared, messy humanity. Editor: This pushes me to revisit all my conceptions about art—its form, function, aesthetic, etc. It asks us what it even is to be creative in artmaking. Curator: Yes, Robert Frank definitely challenges all of those presumptions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.