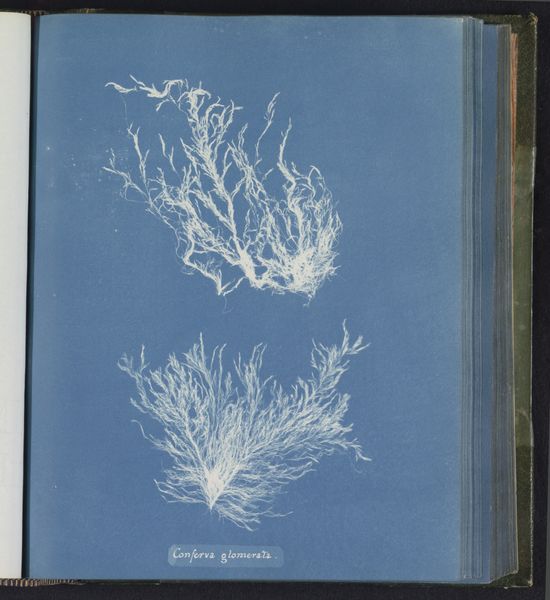

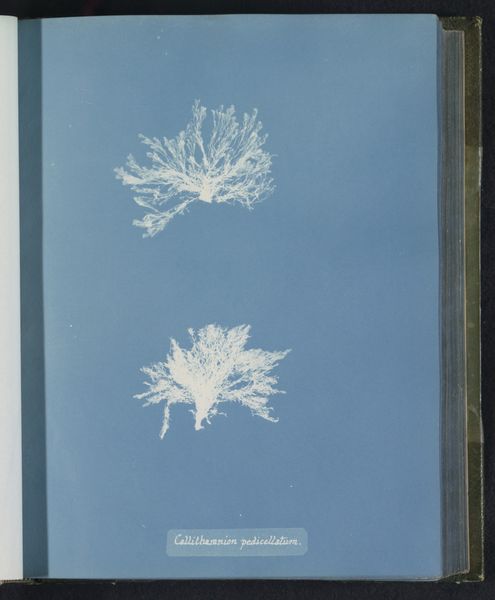

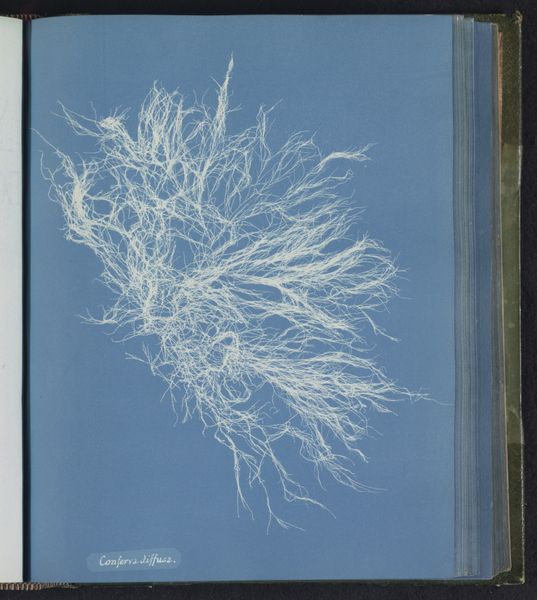

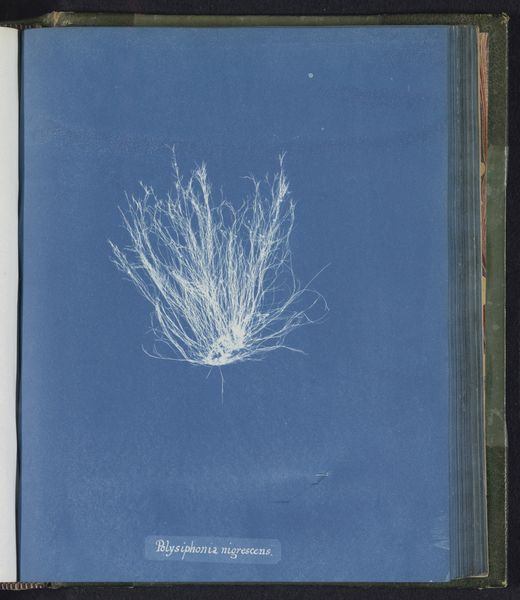

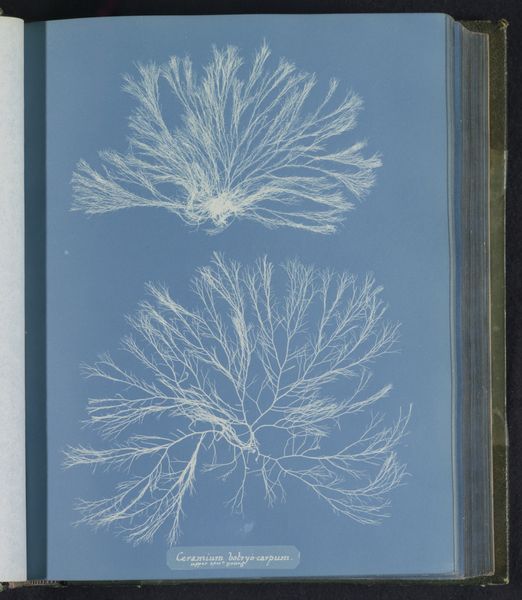

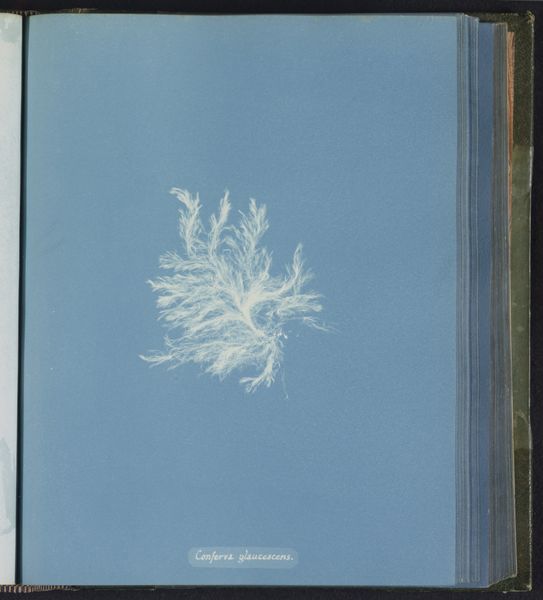

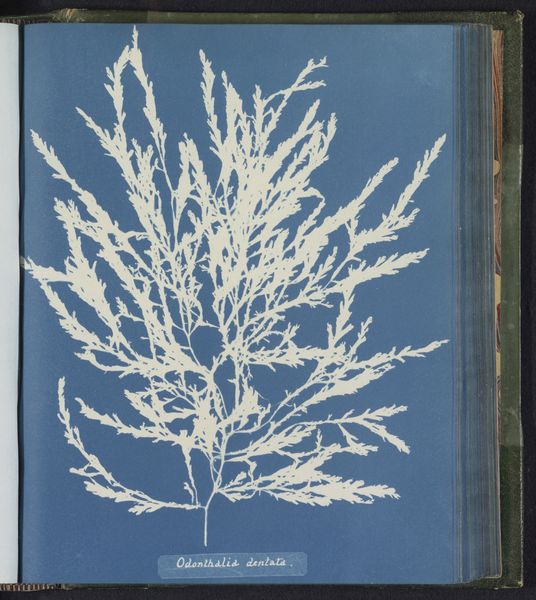

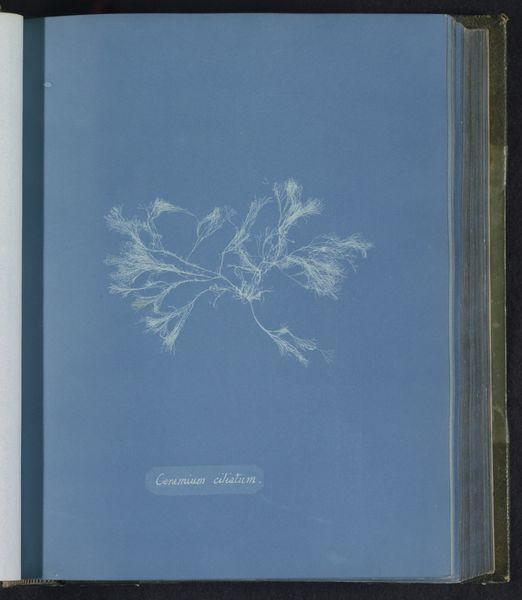

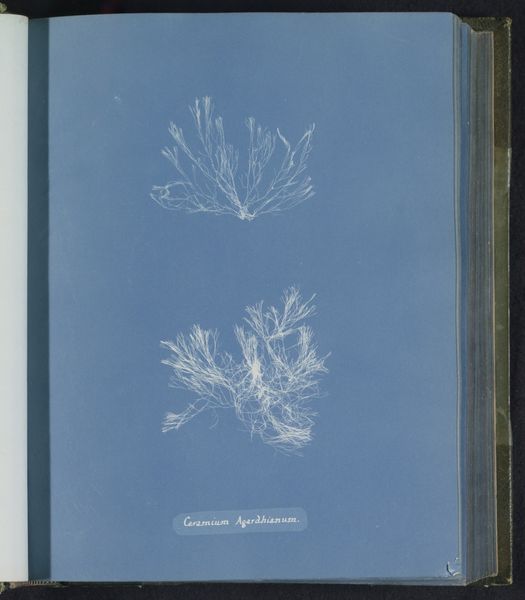

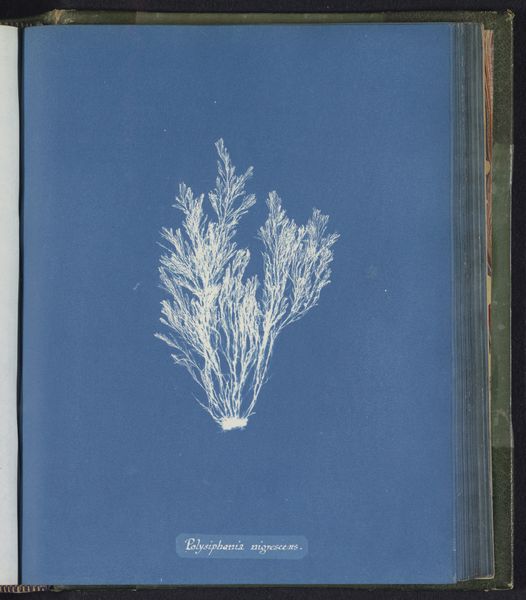

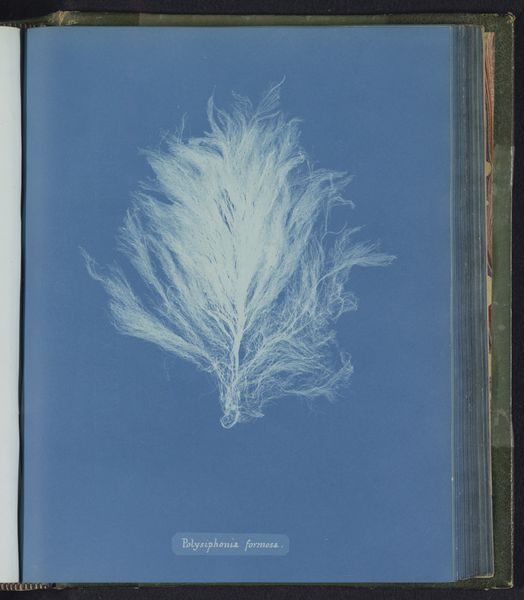

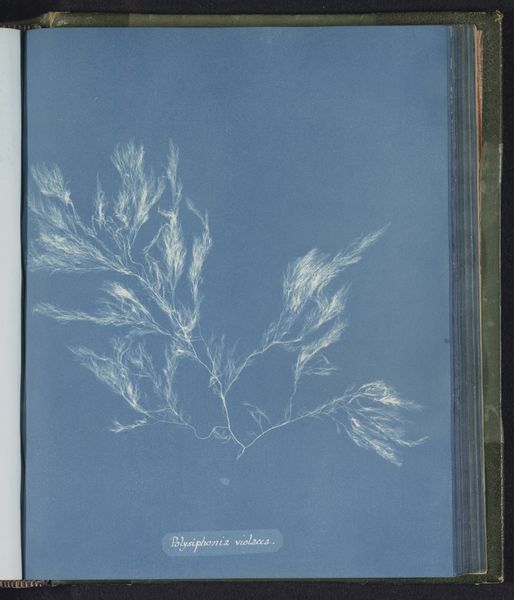

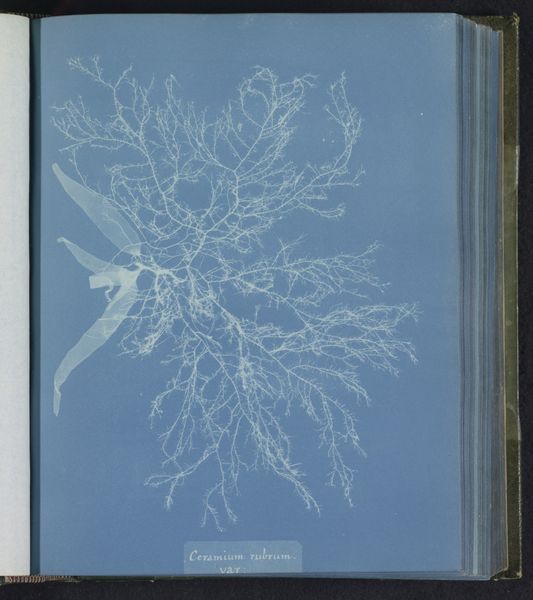

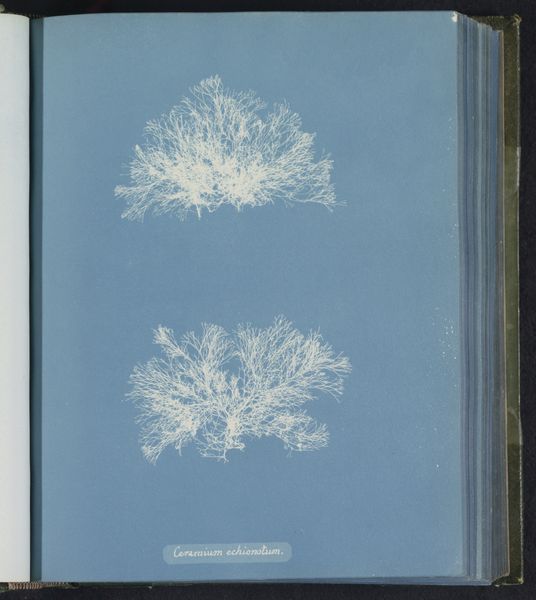

print, paper, cyanotype, photography

#

still-life-photography

# print

#

paper

#

cyanotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

naturalism

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Anna Atkins’ “Callithamnion tetricum,” a cyanotype from around 1843 to 1853. The white algae stands out starkly against the Prussian blue background. It’s so ethereal, like a ghost of a plant. What are your thoughts when you look at this print? Curator: Immediately, I’m drawn to the cyanotype process itself. Think about it: light-sensitive chemicals, the sun's direct agency in creating the image, and paper functioning not just as support but as an active participant. The seaweed becomes a tool of production as well. Editor: So, you're saying the medium is the message? Curator: Precisely. And beyond that, consider the social context. Atkins, a woman in the 19th century, uses a cutting-edge scientific process not for traditional artistic expression, but to document botanical specimens. This challenges the then-rigid separation of art and science, blurring the lines between artistic creation, manual labor, and scientific methodology. What’s craft, what’s art, and who gets to decide? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t considered how subversive using science in art could be back then, especially for a woman. Curator: Absolutely. This wasn't just about making a pretty picture. It was about harnessing a specific, reproducible technology – the cyanotype – for a larger project of scientific dissemination, and maybe even subtle social commentary. How is our understanding different now that the technologies for image making and dissemination are far more democratic? Editor: That’s really broadened my perspective. I initially saw a delicate piece of art, but it’s so much more complex. It makes me consider all of the cultural meanings imbedded within and around its materials. Curator: Indeed, viewing art through the lens of its materials and means of production can unlock a wealth of deeper insights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.