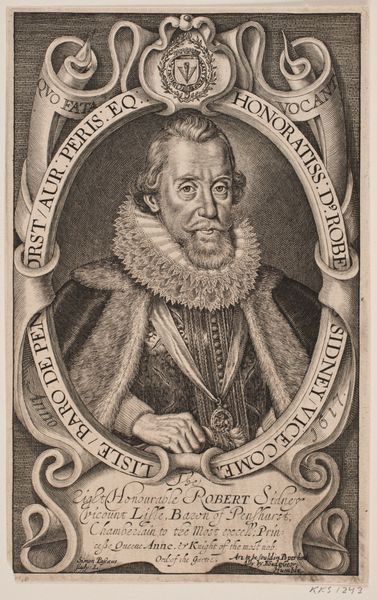

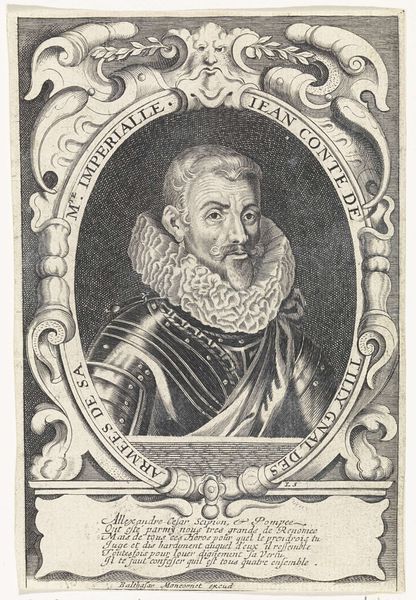

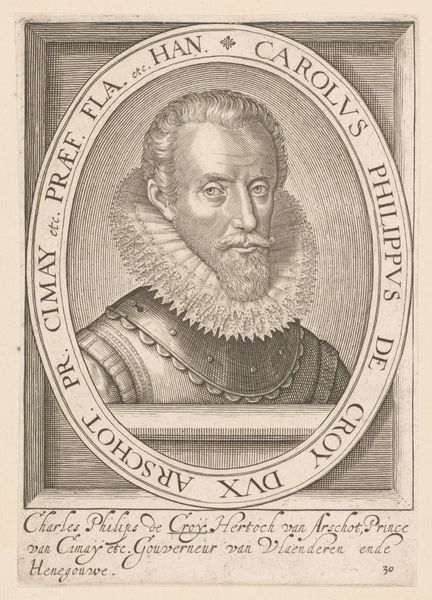

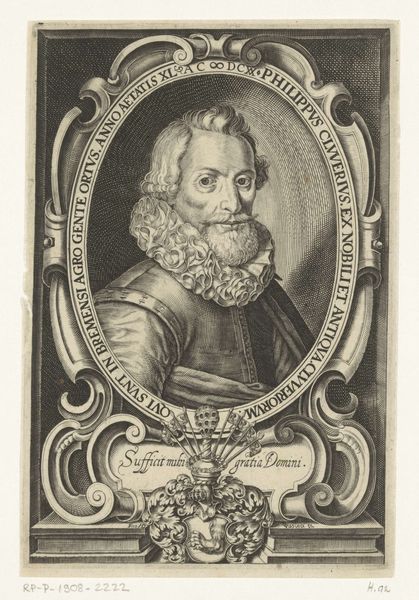

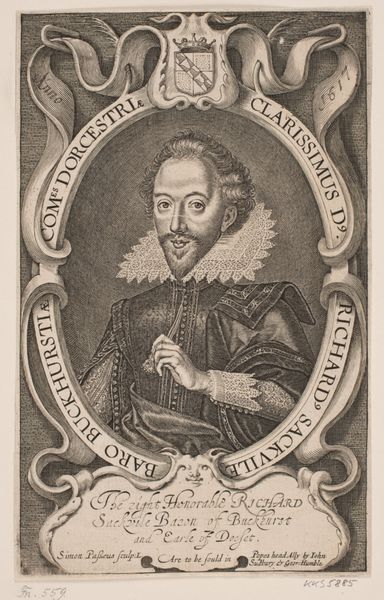

engraving

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

baroque

#

line

#

pen work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 184 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a rather stately engraving, a "Portret van James Hay" by Simon van de Passe, dating back to 1617. It's currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. What strikes me is the incredible detail achieved through engraving alone. How does the medium shape our understanding of the sitter and his status? Curator: As a materialist, I see this engraving as evidence of a very specific mode of production. The process of engraving, the labor involved in creating those precise lines, is central to understanding its value. Engravings, like this, democratized image production and circulation to a certain extent, right? How does this contrast with, say, a painted portrait, in terms of accessibility and the creation of status? Editor: Well, a painted portrait would be unique, for one patron, demonstrating wealth. Whereas the engraving...it speaks to wider dissemination. A type of brand-building, almost? Curator: Exactly. This engraving isn't just a portrait; it's a commodity. The inscription tells us it was “to be sould," actively marketed, impacting who James Hay was targeting, who his contemporaries were engaging. We have the material itself, the engraved plate; the print, a piece of paper sold to potentially hundreds; then we consider the workshops and labor connected. Did that perspective alter the portrait for you at all? Editor: It certainly gives a clearer vision of art as something beyond self-expression - or just about skill – it's inherently bound to production and exchange. Viewing Hay's image now, I understand it more as a designed artefact. Curator: It all goes to show us how artistic skill merges with systems and historical movements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.