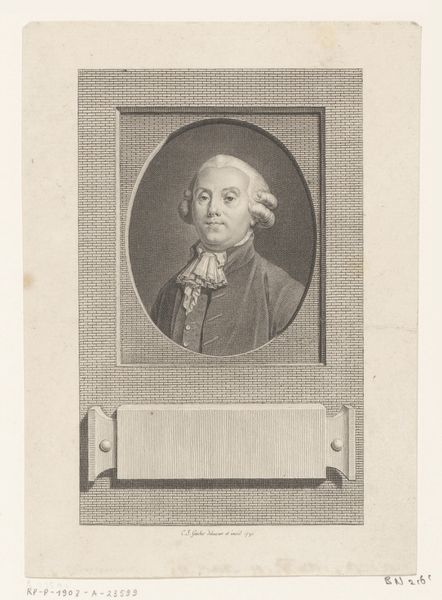

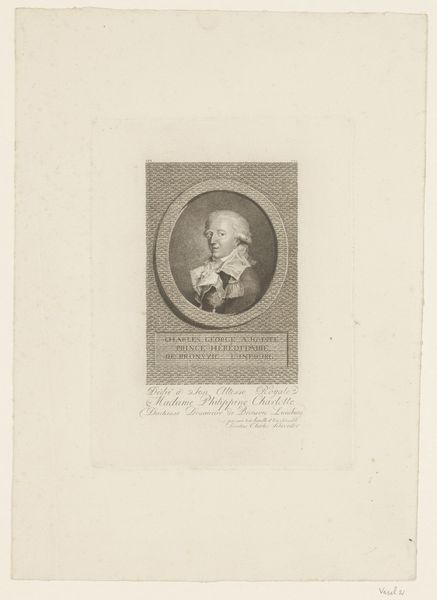

paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

paper

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: At first glance, I find the piece very stark. It’s a portrait encased in geometric shapes. What more can you tell me about it? Curator: Certainly. This is an engraving from around 1800 titled “Portret van Johann Joseph Natter,” and it’s by Carl Hermann Pfeiffer. Note the tight lines and use of paper. Editor: Paper as a medium, though… Doesn't it imply accessibility, a democratizing of the image? Was it meant for broader circulation or for a specific patron? And that engraving, it's labor-intensive, right? How does that tension play out, this availability versus the deliberate, skilled production? Curator: I see your point. Structurally, however, the concentric circles and the lower emblem function as frames. This repetition of form draws our eye toward the center, highlighting the subject's gaze. We see clarity of line. Notice how Pfeiffer uses hatching to construct value and volume. Editor: The line work, sure. But consider the material conditions! Engraving requires a master craftsman, precise tools, specific paper—all influencing the outcome. Curator: Undoubtedly the craftsmanship is crucial. It embodies neoclassical values: order, restraint, and idealization. Note that the line gives us a likeness of the sitter—proportion and detail are key components. The minimal shading helps lend a cool detachment. Editor: Right. Neoclassical values in practice, manifesting via the engraver’s labor and materials. And what was the social context? Who was Natter, and what role did images like these serve? Curator: Context would certainly amplify the piece. Ultimately, for me, it’s a very clean piece of representational art and exemplifies that. Editor: But isn't understanding its means of production and its circulation vital to truly unlocking its meanings? It transforms our interpretation. I mean, someone physically labored over it!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.