drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil

#

15_18th-century

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

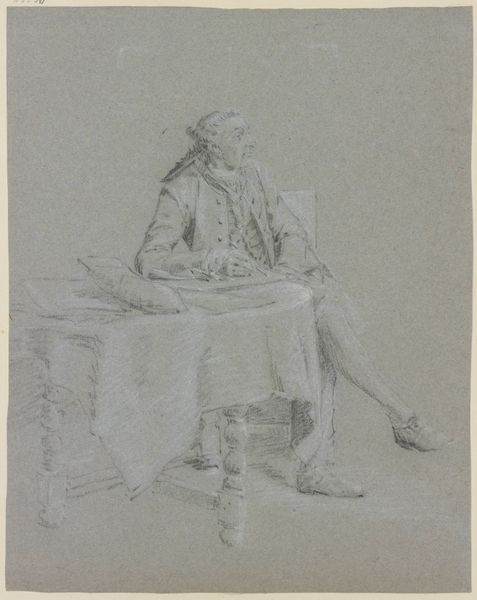

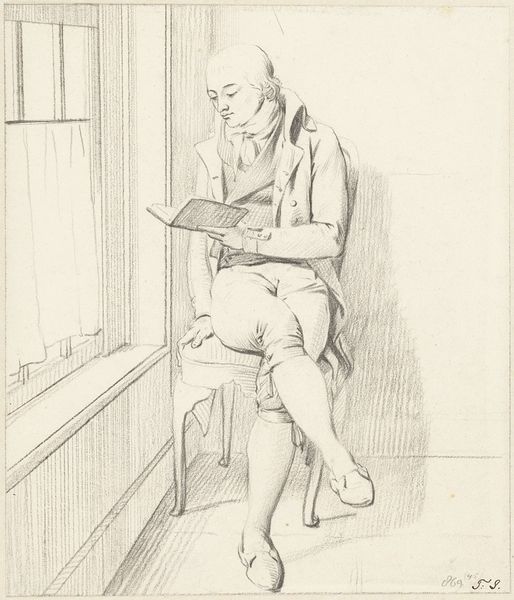

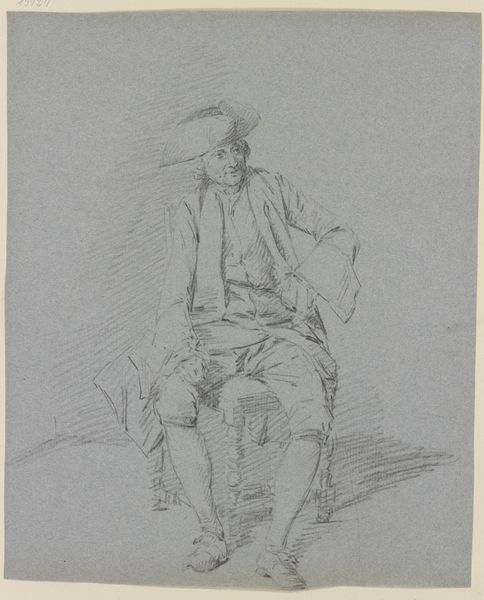

Curator: I’m struck by the almost ephemeral quality of this sketch. It has a lightness to it. Editor: This is Georg Melchior Kraus' "Reading Man," created circa 1765 to 1769. The medium is described as pencil on paper. It is currently held in the Städel Museum. Curator: What does it tell us about the construction of masculinity during that period? We see a man, presumably of some social standing given his dress, entirely absorbed in reading. Is this a performative display of intellect, or a genuine moment of interiority? Editor: Kraus was working in a period heavily influenced by the Enlightenment, where literacy and learning were increasingly associated with virtue and civic duty. The image isn't just a likeness; it’s a statement about the value placed on intellectual pursuits within certain social circles. Curator: It seems that the artist seeks to depict the cultivation of the mind as not simply a passive activity, but an endeavor integral to personal development. I wonder about access, who would be able to afford the luxury of sitting with a book? And further, who would have been granted access to education and literacy, so that they might contemplate philosophical or political notions as demonstrated by the piece. Editor: The socio-economic dimensions are important. Kraus himself navigated patronage systems; he understood how art functioned within a specific social milieu. The soft lines and focused concentration emphasize a type of cultured refinement. It invites viewers to appreciate the virtues associated with reason and erudition. But let us consider the social function. It reinforces hierarchies of class. Curator: Absolutely. By visually enshrining this type of educated man, it implies access to the world of the written word and suggests inherent authority. How did this portrayal affect other disenfranchised identities and social mobility? The soft rendering softens social power as a visual symbol, yet solidifies a legacy, while simultaneously omitting access of the ability for non-traditional or historically excluded subjects to even learn to read. Editor: Looking at Kraus’s broader oeuvre, he seems invested in promoting these ideals of civic responsibility and intellectualism. And how were they consumed and interpreted in the public sphere? Who controlled those spheres of distribution and engagement? Curator: Right. That’s where we begin to disentangle the complex relationship between art, power, and representation during the 18th century. It's fascinating to see it captured so elegantly. Editor: It’s a quiet piece, full of implied meanings that are both universal and deeply rooted in a particular social history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.