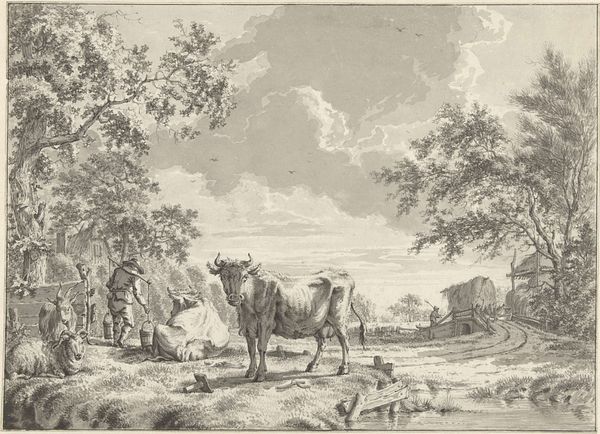

etching, engraving

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

#

etching

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 169 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's turn our attention now to Willem de Heusch's "Landschap met een muildier en geiten," or "Landscape with a Mule and Goats," dating roughly from 1635 to 1692. It’s an etching, meticulously crafted. Editor: Oh, I like this. It’s like a whispered secret, the scratchy lines creating a hazy, pastoral world. Very peaceful, almost meditative. Curator: Considering its creation, what strikes me is the labor involved. Every single line you see required careful planning and execution on a copper plate, reversed in the printing process. Etchings democratized image-making to some degree, making art more accessible, though labor remained central. Editor: Absolutely. But it also makes you appreciate the hand that guided the burin, doesn’t it? You sense de Heusch wandering, sketching, finding beauty in the ordinary. The animals feel like real characters in his play. Look at that goat eyeing us, as if deciding whether we are friend or foe. Curator: Interesting that you focus on the personal gaze embedded within this rendering, but that raises the issue of consumption of these images and what types of circulation was available. Did viewers ponder the actual animals and place as they hung images in the household, or simply admire their compositional aspects, like the careful placing of light and shadow across the land. Editor: It makes you ponder the kind of life led by artist and his audience. Were they city folk dreaming of a rural escape, or did country life also include such quiet, observing moments as the art work seems to propose? This etching is almost whispering to consider one's inner self along the animal's gentle regard. It invites a kind of introspective communion. Curator: A reminder, perhaps, that the materials themselves were becoming globalized commodities – paper, inks, and metals used to create and then spread these pastoral images to a growing consumer class? And what impact this type of image had in relationship to one's own locale? Editor: Yes, that's the funny tension here, right? It speaks to me intimately but its production points outward toward so much greater production, making laboring-classes more precarious even as it allows images of serenity like these to become widespread. In any case, it gives pause. I keep coming back to how gentle, and somehow knowingly cynical it is, no matter the economic contexts around it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.