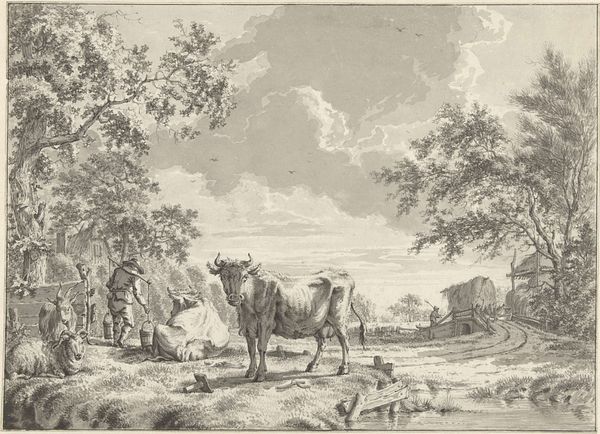

Herder bij zittende vrouw en kinderen bij schapen en twee paarden 1746 - 1811

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: height 142 mm, width 227 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, likely produced between 1746 and 1811, is entitled "Herder bij zittende vrouw en kinderen bij schapen en twee paarden"—or, "Shepherd with seated woman and children with sheep and two horses." Vincent Jansz. van der Vinne is credited with its creation. Editor: It feels quite serene at first glance—a kind of ordered domesticity, despite the presence of livestock and an untamed landscape in the background. I'm drawn to the almost geometric arrangement of the figures. Curator: Indeed. Look at the lines created through the engraver’s technique: the dense hatching creating form and depth. The cross-hatching especially, suggesting textures. But consider the socio-economic realities of the pastoral scene: land ownership, labor divisions within the family unit… Editor: Yes, but consider how the light plays across the scene, defining shape, focusing our attention. The structural simplicity; even the way that the figures’ poses echo each other across the picture plane creates rhythm. How do you factor that in when we’re simply looking at historical accounts? Curator: I believe we must remember that aesthetic choices are shaped by practical considerations of resources available and constraints by workshop traditions of print making, of the societal role of landscape imagery that idealize agrarian work, and masking the true difficulties experienced by those dependent on seasonal, fluctuating market economy and labor. Editor: Perhaps, and I respect that approach to the artist’s hand and socioeconomic standing reflected in artistic production. However, in a reading through formalism, the rhythm present—this pastoral simplicity that may actually offer us something aesthetically, and emotionally as well. The piece creates an emotional affect that isn’t only tied to work life. Curator: The effect, though, would not exist outside the social. These depictions and depictions that are widely accessible through print serve a certain role as social markers for patrons too. The engraver and the artist were part of these networks of workshops, apprenticeship and patronage. We must examine the relationship with the rise of commercial landscape and its place in the era. Editor: Perhaps, in thinking more on it, the true accomplishment might lie within Van der Vinne’s use of form in relation to this context, using those means for societal promotion in this case. Curator: It seems the engraving does reflect multiple facets that could encourage rich discussions of image-making in society and culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.