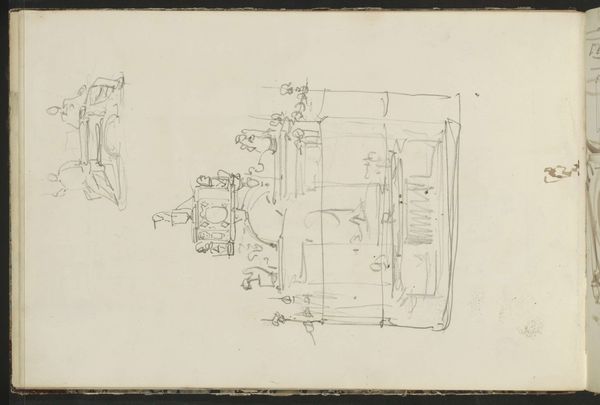

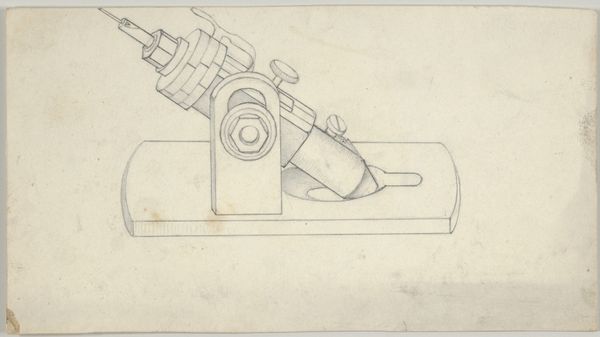

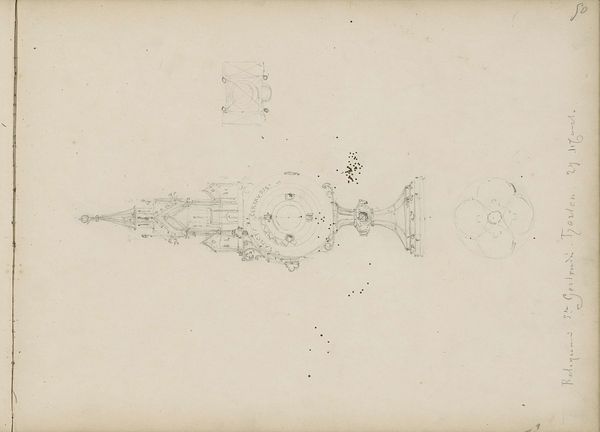

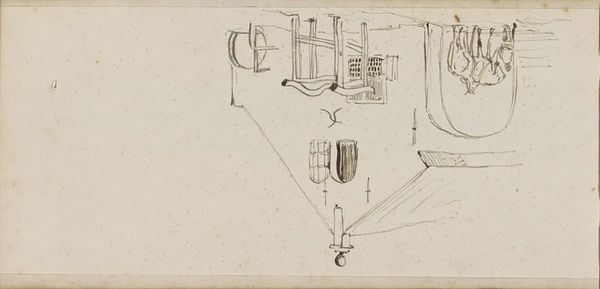

drawing, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

ink

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

cityscape

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

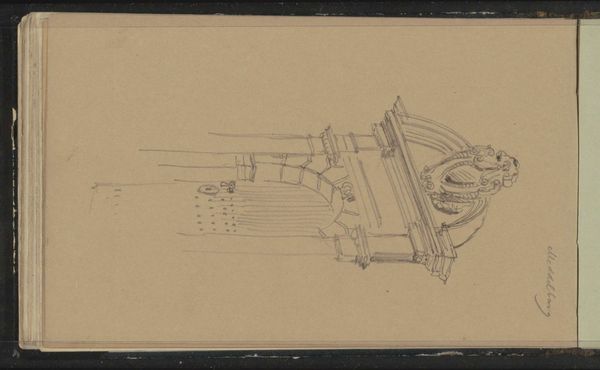

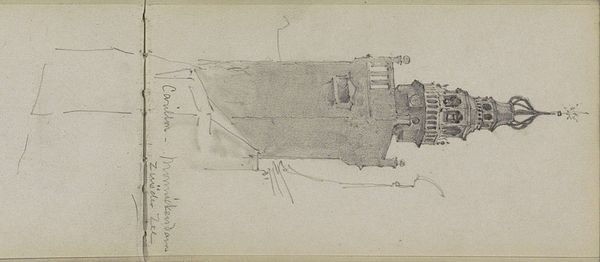

Curator: This piece, titled "Hoofdtoren te Hoorn," is a pen and ink drawing by Adrianus Eversen, dating back to somewhere between 1828 and 1897. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the almost ghostly quality of the sketch. It’s unfinished, raw—a fleeting glimpse of a cityscape, rendered in the most economical way. There’s an undeniable melancholy to its sparse lines. Curator: Indeed. Eversen, deeply rooted in Realism, presents us with an opportunity to contemplate how architecture—especially structures of civic importance like this tower—figures into the broader narrative of urbanization and its effect on the populace. I also notice the tower and small sketch seemingly floating in the empty space of the paper which, like a deconstructed mind-map, evokes a meditation on the symbolic dimensions of civic history itself. Editor: And I find myself questioning how his style resists idealizing this subject. Instead, by laying bare the rudimentary, he implicitly offers us a commentary on social structures. What kind of power dynamic can be read within the unembellished, sketched aesthetic and how does its urban subject help the reading? Curator: I believe its socio-political value also relies on its form, drawing, offering it a distinct role within 19th century Holland. This style can provide historical insight, echoing themes of transparency, truth, and democratization – values fermenting as that society grappled with significant political and social changes. And who was the drawing made for and how accessible was its style and message to the wider population? Editor: The materiality itself invites us into the discussion, doesn’t it? Ink on paper, a relatively inexpensive medium, grants access, opening possibilities for dissemination. It subtly democratizes representation, moving art away from strictly aristocratic domains. Curator: Well observed. We can read this in dialogue with contemporaneous sociological thought—how representations of place can reinforce or challenge class-based spatial segregation. What ideologies of accessibility and control might be at play here? Editor: This has reshaped my appreciation of its visual story, to think through the intersections between style and its time, how simple renderings can communicate the complex dynamics that define societal norms. Curator: I agree. Examining art within the matrix of social history gives us deeper knowledge. It allows us to be aware of its original settings and relevance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.