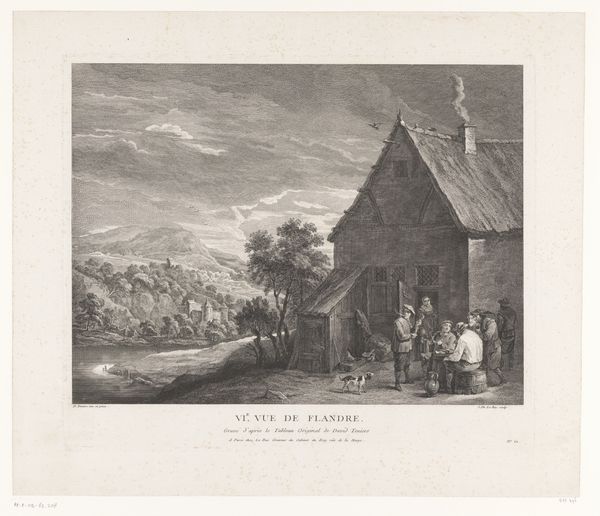

Dimensions: height 255 mm, width 307 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: First impressions? What do you make of this landscape, this slice of 18th-century Flanders rendered in monochrome? Editor: It feels…quietly theatrical. Like a stage set, the way the figures cluster outside the inn against that sweeping backdrop. There's a stillness, a pregnant pause, before some bucolic drama unfolds. What's the story here? Curator: This engraving is entitled “Landscape with a Company by an Inn,” created by Jeremias Wachsmuth, active roughly between 1755 and 1771, now held at the Rijksmuseum. It's after a painting by David Teniers the Younger, a Flemish artist celebrated for his genre scenes. These scenes idealized peasant life, blending observation with sentimental fancy for an aristocratic clientele. Editor: Idealized peasant life, you say? Looks a little gloomy to me! All muted greys, despite being quite detailed; even the revelry outside that inn feels a touch melancholic. Everyone's just…there. Staged, as I was saying. Like posing for a picture of happiness that’s not quite believable. Curator: That contrast between representation and lived reality is fascinating. These prints served a crucial social function, circulating images and shaping perceptions of rural life for urban audiences. Was it "real?" Of course not. It served to construct the world, and to invite the urban aristocracy to perceive the rural working class from the comfort of their salons. The print format allowed for broad dissemination. Editor: Makes me wonder about the role of art in crafting these narratives. What gets emphasized? What conveniently gets left out? The hard labour, the exploitation – conveniently omitted in favor of simple pleasures. Though, as you say, Wachsmuth may have emphasized the landscape precisely to romanticize or even exoticize it. I still love it! It looks cozy but in an antiquated way; cozy on stage. Curator: I'd agree. Perhaps such engravings allowed people of the time to construct an identity and a shared cultural history through images that celebrated a particular kind of scenery. Editor: So, ultimately, beyond being beautiful – this landscape becomes a powerful mirror reflecting both then and now. Art creates conversations about society that sometimes tell more truth than we can easily see.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.