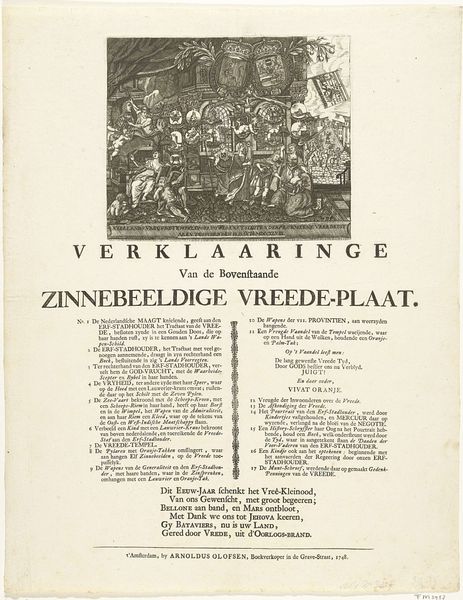

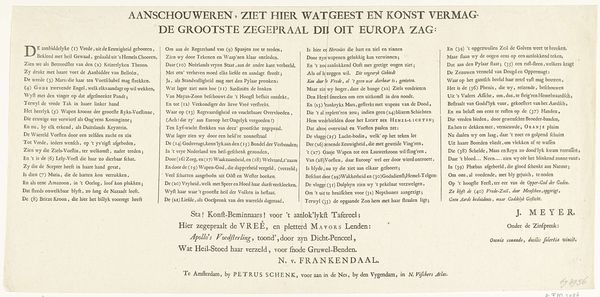

print, engraving

#

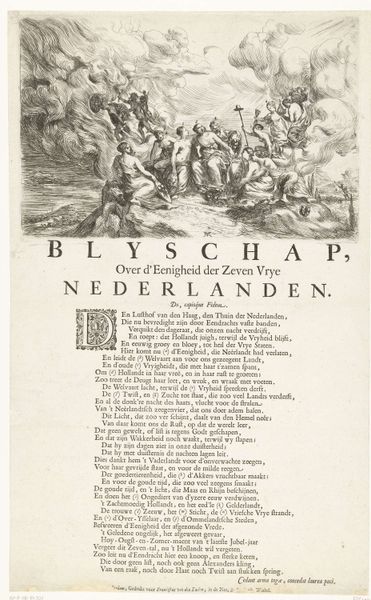

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

text

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 387 mm, width 231 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Allegorie op de verheffing van Willem IV," or "Allegory on the elevation of William IV," an engraving dating back to 1747 by Wenceslaus Hollar, housed at the Rijksmuseum. It’s predominantly text with a symbolic image at the top – lions flanking a sapling. The piece, despite its age, feels incredibly… deliberate. What strikes you most about it? Curator: It's interesting how the image, the text, and its historical moment intersect. Hollar’s piece speaks volumes about production under political pressure. Engravings like this served as readily reproducible tools of propaganda, aligning the House of Orange with strength and continuity. Note the *means* of production here – printmaking allows for widespread distribution, influencing public perception in a way painting simply couldn’t at the time. What does the *materiality* of the engraving, versus another medium, suggest about its purpose? Editor: It suggests accessibility. Prints were far cheaper to produce and distribute than paintings, therefore reaching a broader audience was easier. So, the very nature of engraving facilitates a certain democratisation of the image? Curator: Precisely! It wasn't about individual patronage but a collective message to the Dutch populace. The print *is* the message as it spreads. And what of the text itself? How does its construction influence meaning, considering that this artwork is an engraving meant for reproduction, cheap distribution and popular influence? Editor: Well, the poem reinforces the symbolism. The tree is Willem IV, his lineage deeply rooted, destined to bring prosperity. I suppose it highlights that while the image is powerful, its partnership with readily legible text provides instruction on precisely *how* it’s to be interpreted? Curator: Exactly. The poem makes the image understandable for a popular audience. But let's not forget Hollar’s role. He wasn’t just an artist; he was a craftsman working within specific socioeconomic constraints to disseminate a very particular narrative. Considering all this, how does this piece challenge the traditional distinction between "high art" and a more functional, political form? Editor: It blurs the lines significantly. The material choices, the reproductive nature of the print, the poem… it was all calculated to produce a specific reaction, moving beyond mere aesthetics. Curator: It’s about understanding how political context shaped both production and reception. We see art not as existing in some neutral zone but directly influenced by social pressures and consumption practices.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.