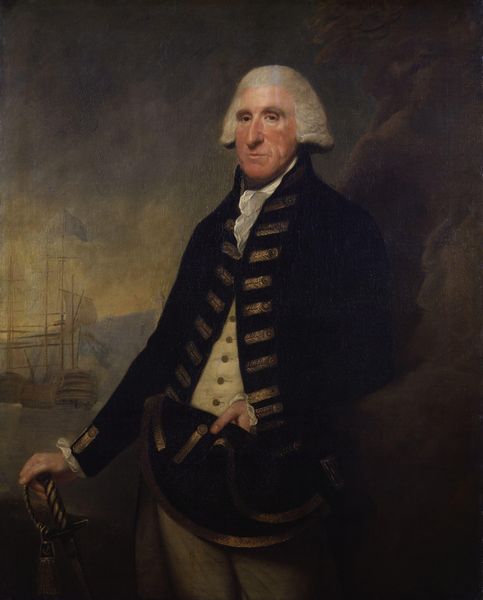

Dimensions: 127 × 101.6 cm (50 × 40 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Up next we have John Wollaston's "Portrait of a Naval Officer," painted sometime between 1749 and 1758. Editor: My first thought is how meticulously rendered the materials of his uniform are, the textures and weight seem palpable. Curator: Wollaston was highly sought-after for his ability to capture likenesses, but his paintings also offer insights into the societal structures of the period. Note the emphasis on the naval officer's attire. In the 18th century, clothing was integral to establishing one's social and professional identity. This portrait reflects colonial hierarchies, wealth, and military power, especially considering Wollaston's work catered largely to the colonial elite in America. Editor: Exactly! You can see it in the details: the gold trim of the jacket, the polished buttons— each element speaks to the officer’s status and access to finely crafted goods. Consider the labor and materials involved: the wool dyed for the uniform, the tailoring. This speaks volumes about production and trade routes tied into Britain's naval reach during the period. Curator: Moreover, I wonder about the subject himself. Was this portrait intended to bolster his own ambitions, or those of the empire? These portraits legitimized power structures by reinforcing conventional symbols and social ideals. Editor: I think there’s tension between this man, who most probably ordered his portrait and its visual messaging of belonging, class, and industry and those who were outside of that elite. In this context it may offer as much critical social commentary than perhaps it meant at its making. Curator: Perhaps Wollaston unwittingly unveiled the very power structures he served. Art reveals so much about history, doesn’t it? Editor: It does. Studying artmaking within the framework of material conditions is truly revealing, yes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.