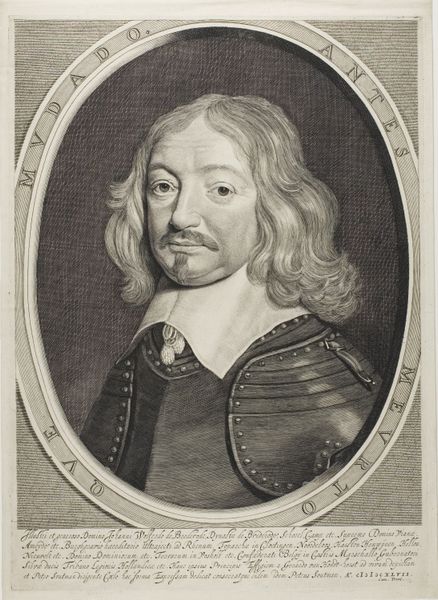

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 88 mm, height 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pieter van Gunst’s engraving, “Portret van Oliver Cromwell,” made sometime between 1659 and 1731. It's a striking portrait. There's a lot of formality to it, but Cromwell’s eyes give a sense of… vulnerability, maybe? What do you see in this piece? Curator: That vulnerability you perceive is fascinating, considering Cromwell's controversial legacy. This portrait, made posthumously, exists in a complex space. It was produced in a time grappling with the aftermath of revolution and regicide. The print becomes a tool for constructing and contesting historical narratives. Editor: Could you expand on that? What kind of narratives? Curator: Consider how this image functions within a society that executed its king. The armor speaks of power, the gaze – as you observed – hints at human frailty. Does the artist memorialize a leader or subtly critique the complexities of power and its effects on the individual? What do you make of the ornamental frame and the coat-of-arms below the portrait? Editor: They seem to legitimize Cromwell, almost like a royal portrait. But it feels forced, doesn’t it? Like they’re trying too hard to create that image. Curator: Precisely. The artist appropriates the visual language of power while simultaneously leaving space for doubt. Perhaps the choice of engraving, a medium accessible to a wider public, invites broader participation in this ongoing debate. The lines composing the portrait can also be interpreted as boundaries constantly redrawn in history. Editor: That's a powerful idea! I hadn’t considered how the medium itself plays into the political message. Curator: It’s in these contradictions, these tensions, that art history becomes truly engaging. Considering not just *what* is represented but *how* and *why* allows us to excavate the layers of meaning embedded in the artwork and its reception. Editor: This has really changed my perception of portraiture! Thanks for your insights. Curator: Likewise. It is in open dialogue that we keep historical perspectives alive.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.