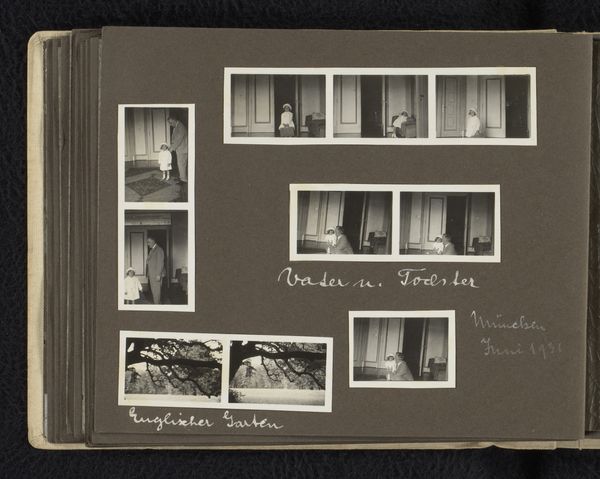

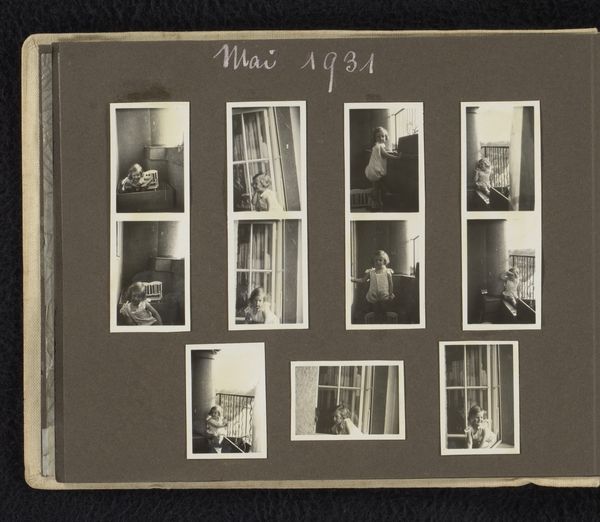

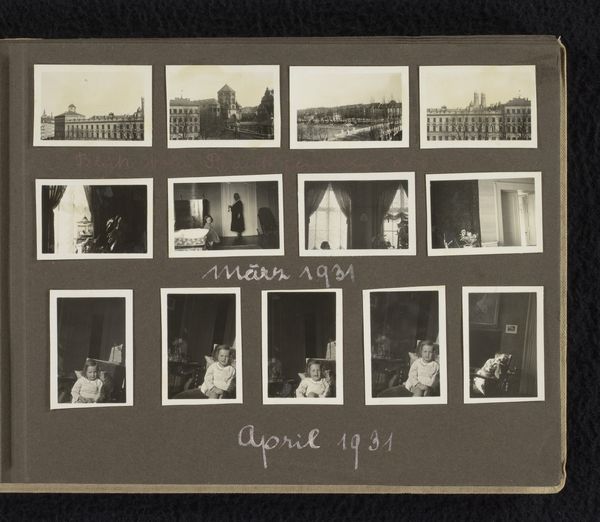

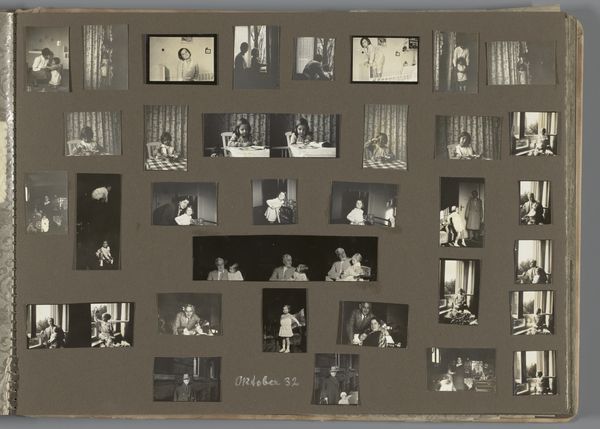

Isabel Wachenheimer wacht af totdat ze naar de kapper mag, met haar moeder Else Wachenheimer-Moos, juni 1931, München 1931 - 1936

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

intimism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 27 mm, width 40 mm, height 150 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

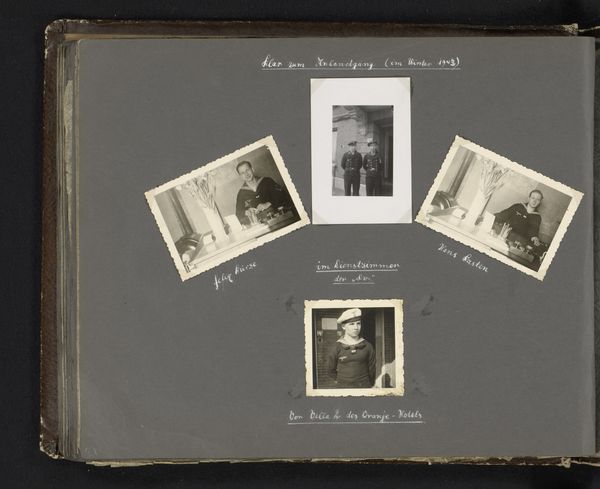

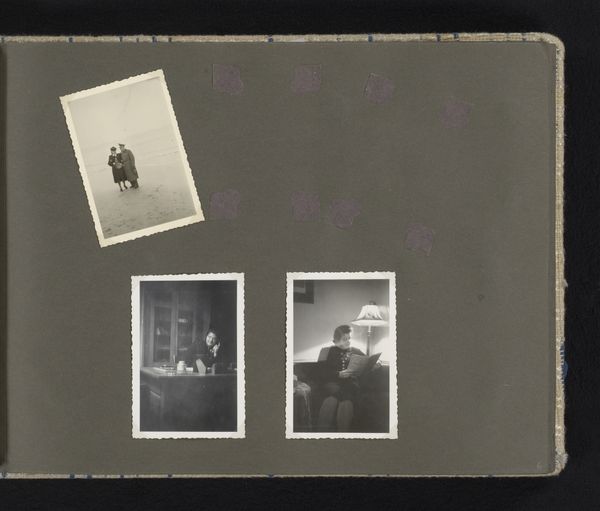

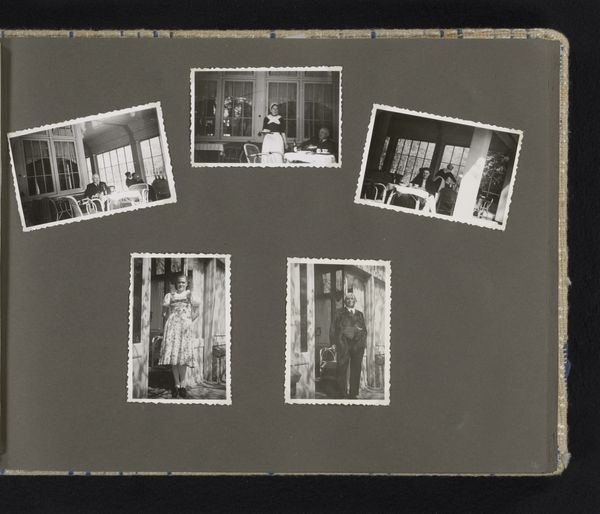

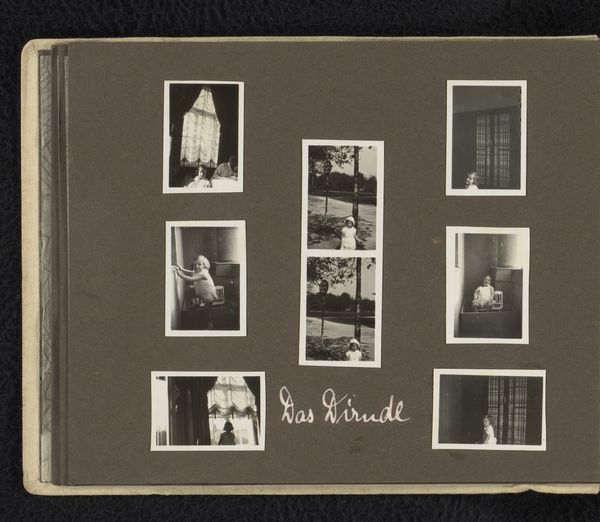

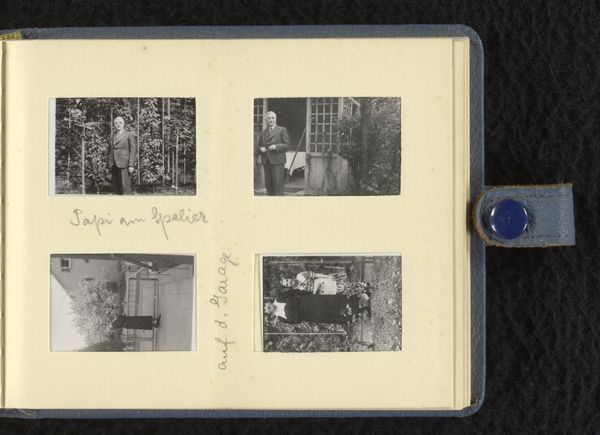

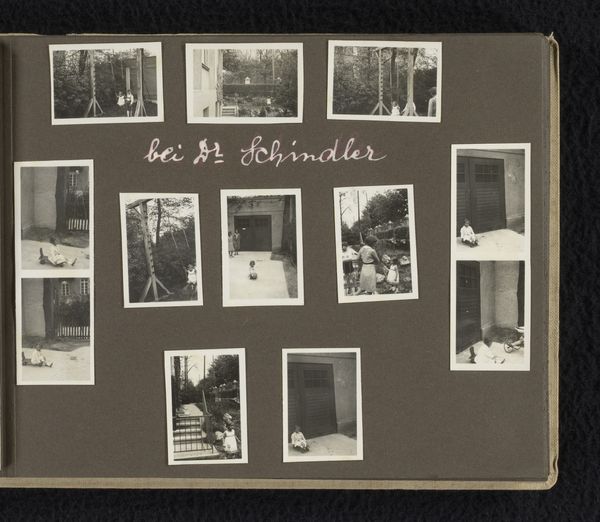

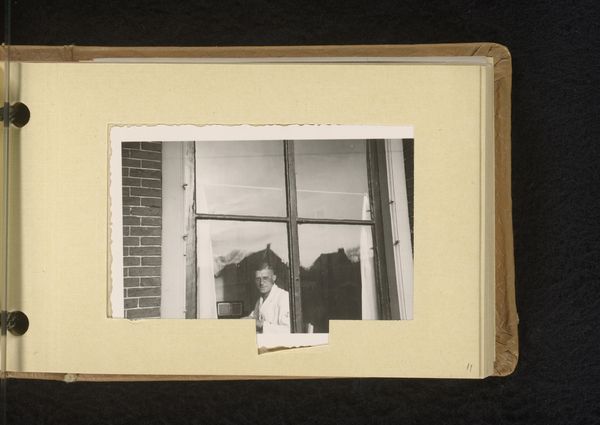

Curator: The collection holds gelatin-silver prints assembled by the Wachenheimer family. Here, we see an album page dated June 1931, featuring Isabel Wachenheimer and her mother, Else. What's your initial reaction? Editor: I'm struck by the domesticity, and slight humor—a child awaiting a haircut, documented in a series of images, framed like a storyboard. The grey tones convey such an intimate, ordinary scene. Curator: It does. The snapshots offer us an insight into the intimism of bourgeois life between the wars, focusing on the maternal bond and mundane aspects of family rituals. Isabel's gaze towards the camera invites speculation about children's place within these social structures and the construction of girlhood identity. Editor: Agreed. Considering the materiality, these silver gelatin prints would have been created in a darkroom using relatively accessible photographic equipment. This emphasizes the act of documentation and its significance in archiving memory and class identity, highlighting the role of photography within a family's narrative construction and personal consumption. Curator: Exactly. The historical weight comes from knowing that these subjects, photographed during what appears a time of innocent waiting, would have their lives dramatically impacted by Nazi persecution. These family archives act as critical sites of memory. They challenge the grand narratives of history with intensely personal stories. Editor: I am wondering, what were the working conditions in photographic studios, what sort of darkroom resources were required to produce gelatin silver prints en masse for family albums in the interwar period? Who were the hands, the chemical companies, who contributed to this visual record? Curator: I like where you’re going. It encourages us to reconsider the means of image-making within the larger structure of labor, class, and, ultimately, consumption and dissemination. Editor: Precisely. Studying the social network around the material history of photography reveals connections to historical factors far beyond simple aesthetic choices. These are traces, each stage imprinting socio-historical conditions on emulsion and paper. Curator: Understanding photographs like this through the intersections of material, social, and familial factors enriches our perspectives regarding gender, labour, and the volatile dynamics of their era. Editor: Definitely, and examining process, we uncover hidden structures that often shape our view of past realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.