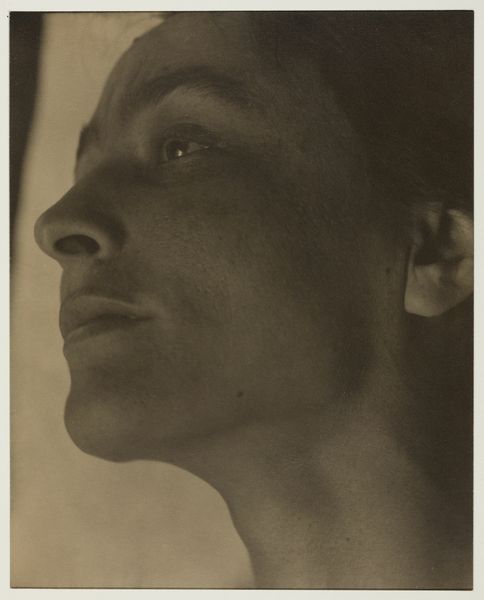

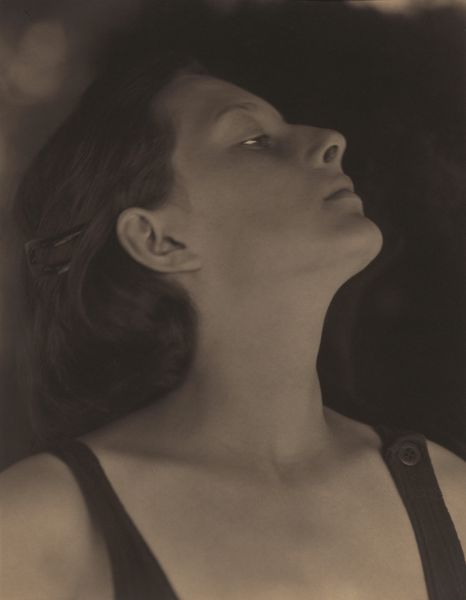

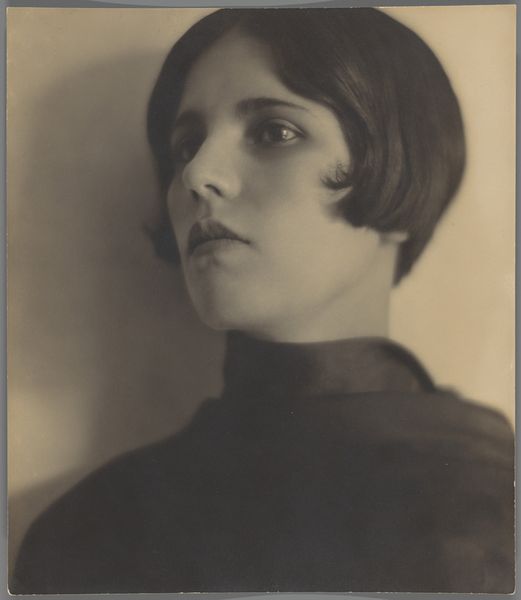

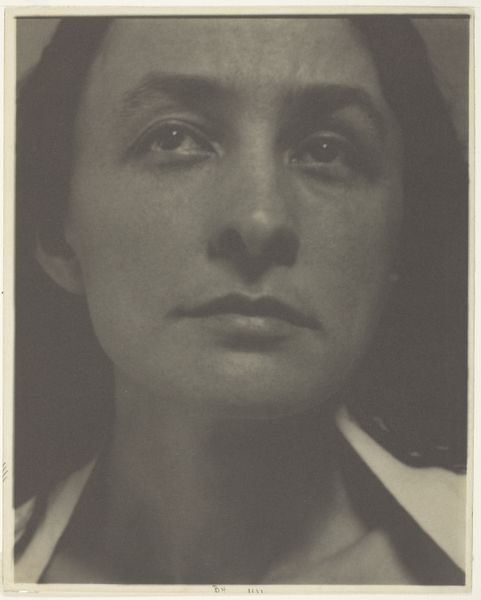

photography, gelatin-silver-print, silver-point

#

portrait

#

pictorialism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

silver-point

#

modernism

Dimensions: image: 23.9 × 19.3 cm (9 7/16 × 7 5/8 in.) sheet: 25.1 × 20.2 cm (9 7/8 × 7 15/16 in.) mat: 54.2 × 45.8 cm (21 5/16 × 18 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Ah, yes, "Helen Freeman," a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, created around 1921. Editor: She’s lost in thought, or maybe lost in hope? There's an intense longing captured in her gaze. Almost unnervingly so. Curator: Stieglitz often captured such interiority, wouldn’t you agree? Think of his cloud studies, his Georgia O'Keeffe portraits… He was always seeking to photograph not just what was visible, but what was felt, or yearned for. In his work here we find him combining techniques characteristic of pictorialism and early modernist photography: a gelatin silver print, manipulated by hand, almost akin to a silver-point drawing. Editor: It’s an incredibly material process. You can almost feel the layers – the photographer's hand working in the darkroom, the chemicals reacting, the way light interacts with the emulsion on the paper. The resulting print isn't just a photograph; it's a made object, a collaboration between the artist, the subject, and the materials. Do we know the origin of these materials – the gelatin, the silver? Was it a cottage industry or large-scale production? Curator: Interesting questions! We know Stieglitz saw the potential in photography as a means of achieving something akin to what painters and sculptors accomplished with their chosen materials, rather than merely using the camera as a tool for recording facts. It elevates it to an art, makes it speak, and this portrait absolutely speaks. Do you see the softness, the light on her skin, her gaze fixed upwards? She embodies a dream, or aspiration. Editor: True, but the tangible reality of producing such images also deserves consideration. Silver was extracted and refined. Someone had to prepare the gelatin, coat the paper. Looking at it in this way reveals a complex history of industry and labor embedded in a single image that's all too often romanticized as simply reflecting inner emotion. Curator: And yet the humanity… it pulls us in! The slight tilt of her head, the way her garment subtly suggests both vulnerability and defiance…it's undeniably beautiful and evocative. Even now. Editor: Agreed. Beauty arises in a given historical setting through those interactions: between hand, machine, human subject, and raw materials. It changes how we consider the art in this frame. Curator: It reminds us, then, that a work of art is never just one thing, but rather a dance between intention and material, seen and unseen, known and yearned for. Editor: Indeed. Seeing those layers helps us appreciate the photo as an important record of both individual emotion and broader social forces that came together in its making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.