print, photography

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

Dimensions: height 67 mm, width 106 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

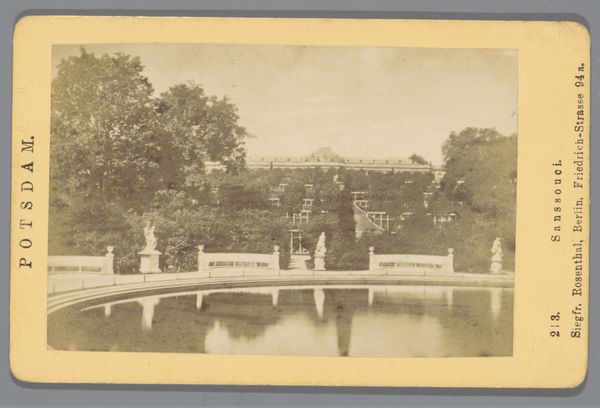

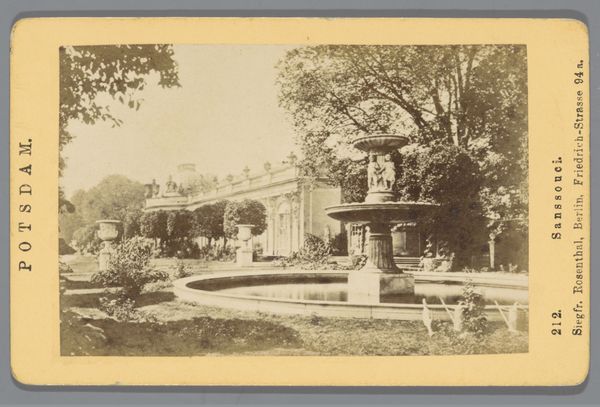

Curator: What a striking image. We’re looking at a print from between 1868 and 1880 entitled *Tuin van paleis Schönbrunn, Wenen*, or *Garden of Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna*, produced by M. Frankenstein & Co. using photography. Editor: My first impression is of controlled nature. It feels meticulously designed, a very deliberate ordering of the landscape, bathed in sepia tones giving a kind of nostalgic detachment. Curator: Precisely. The formal gardens of Schönbrunn were designed to project imperial power, reflecting the Habsburgs’ ambition to create a visual language of control and dominion. Note how the carefully sculpted hedges and the architecture act almost like stagecraft. Editor: Absolutely, I see those allegorical sculptures flanking the long walk too, barely visible within the hedging, reinforcing classical virtues for the benefit of the viewer, but is that really successful? They seem dwarfed somehow by the overall design, barely noticeable! It makes me consider the power dynamics between humanity, culture, and nature itself. Curator: The choice to depict this order through photography itself reinforces this, offering a seemingly objective snapshot of established authority. Though, even in photography, there’s deliberate framing: this view culminating with the Gloriette acts as a kind of ideological focal point. The monument’s use speaks of triumph and justification. Editor: So it becomes a political landscape presented as an idyll? The print medium would suggest that this was targeted for consumption, wasn’t it, reinforcing notions of a perfect society governed by imperial benevolence. Curator: It speaks to a particular moment, doesn't it? As photography democratized image-making, those in power could easily mobilize and control such imagery to consolidate their dominance through these idyllic and romantic visions of imperial success. Editor: It's powerful to consider the many layers, from the physical gardens to the photographic reproduction. There’s the designed landscape meant to shape understanding of power; the careful artistic mediation of the photographer capturing it; and finally, we encounter a deliberate attempt to influence broader public opinion through wide distribution as a print. Curator: It leaves me thinking about the layers of representation – the real garden, the image of the garden, and our present-day viewing. What cultural memories and assumptions are projected onto it, both then and now?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.