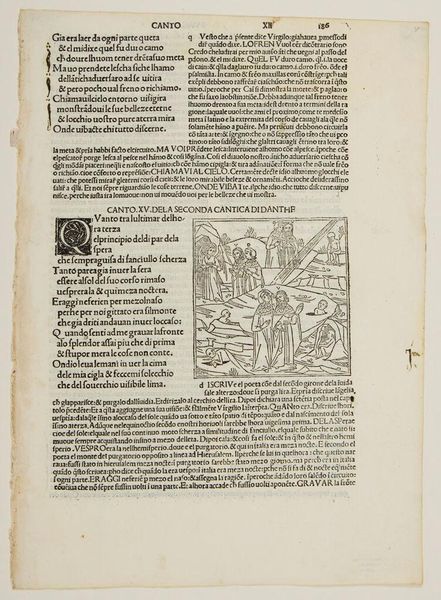

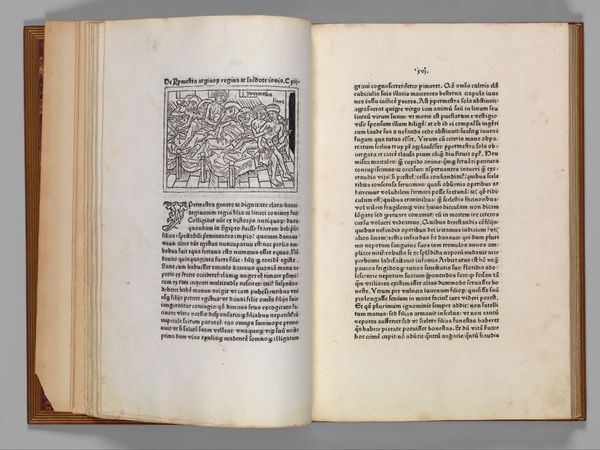

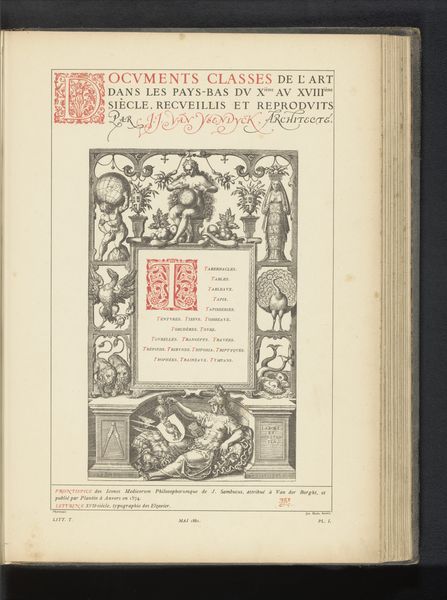

drawing, print, paper, woodcut

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

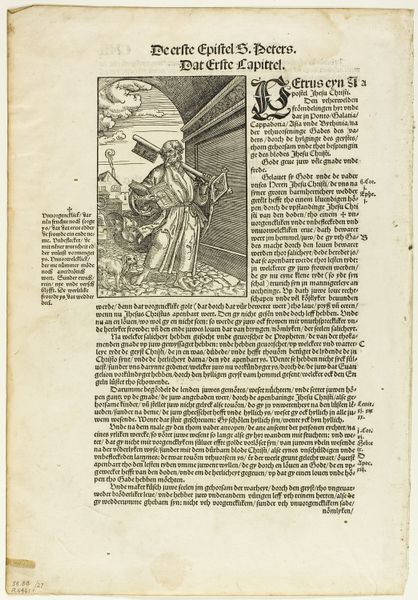

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

woodcut

#

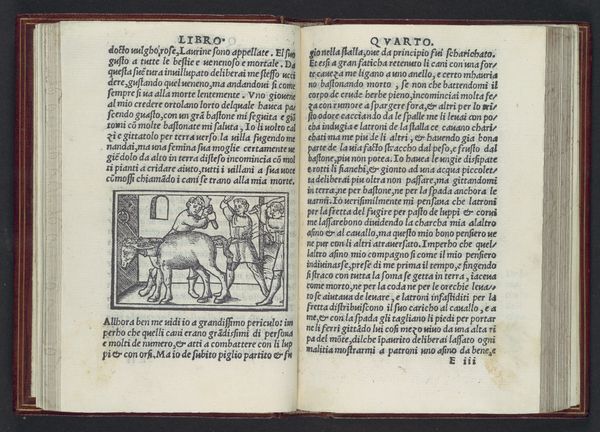

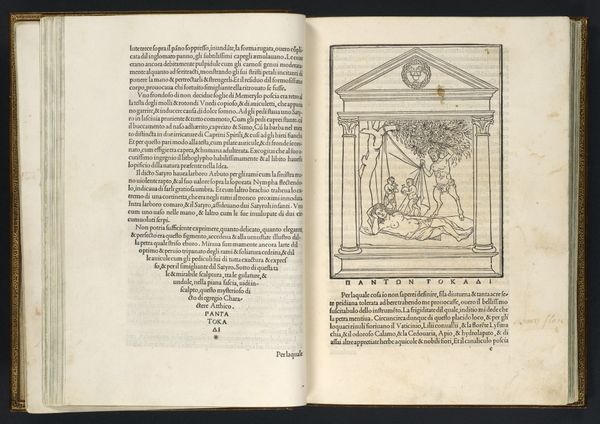

italian-renaissance

#

miniature

Dimensions: 11 1/8 x 8 3/8 x 1/2 in. (28.3 x 21.3 x 1.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at this fascinating Renaissance-era print now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It's a woodcut illustration, part of Federico Frezzi’s *Quatriregio*, or *Four Realms*, dating from 1508. Editor: My immediate reaction is how intricate yet delicate the image is, especially given that it's a woodcut. It feels almost like a miniature tapestry with all its details. A sort of mythical forest. Curator: The choice of medium is quite relevant. Woodcut, while allowing for a wide distribution due to printing, inherently carries a sense of craft and traditional artistry. In terms of symbols, consider how the artist uses familiar classical imagery. Editor: The symbolism, though, feels... well, expected. We have Diana, nymphs, suggestions of classical stories—elements very much aligned with the visual language cultivated in the Italian Renaissance. Are there some less obvious psychological meanings? Curator: Absolutely, I think there's a rich undercurrent to explore here. Take the presence of Diana in a seemingly pure landscape setting, this relates to ideas of a primal connection between humans and nature but can be read, also, through the psychological themes of freedom and wildness. Diana could mean that a state of nature is desired, outside of all that order displayed by the Renaissance at the time, if we accept those conventions in art, in dress. Editor: So you're suggesting a dialogue between a yearning for something outside those structures, a desire for freedom, juxtaposed with those very conventional forms? The woodcut style itself becomes symbolic, almost like a framework—literally— containing this potential rebellion. Curator: Precisely, it shows us a society negotiating its values through art, making explicit reference to its classical inheritance, and its emerging needs. The inclusion of text with image allows for multiple readings for a public well versed in those references. Editor: And, by analyzing the choice of figuration we understand those narratives that reflect collective cultural beliefs and political agendas. It reminds us that visual stories are always constructed in their context. Curator: Indeed, the image operates not in isolation but as part of an exchange, culturally and politically. We can study how institutions then—and museums now—are vital actors in defining such stories. Editor: Yes. Exploring images like *Quatriregio*, opens paths toward a nuanced dialogue with our historical perspectives and what our idea of beauty is. Curator: Ultimately, engaging with these detailed woodcuts lets us decipher how past societies made sense of their ever-changing landscapes of both thought and place.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.