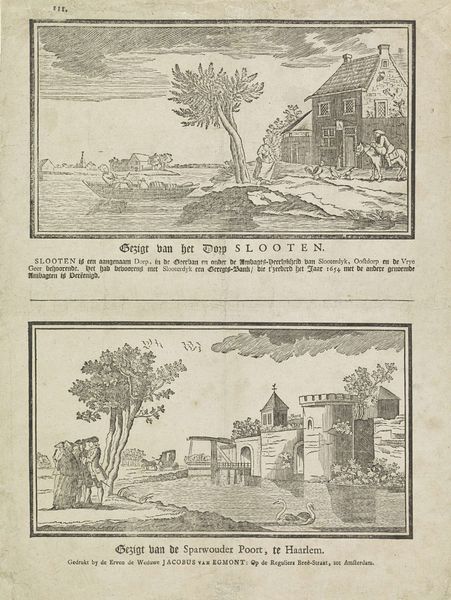

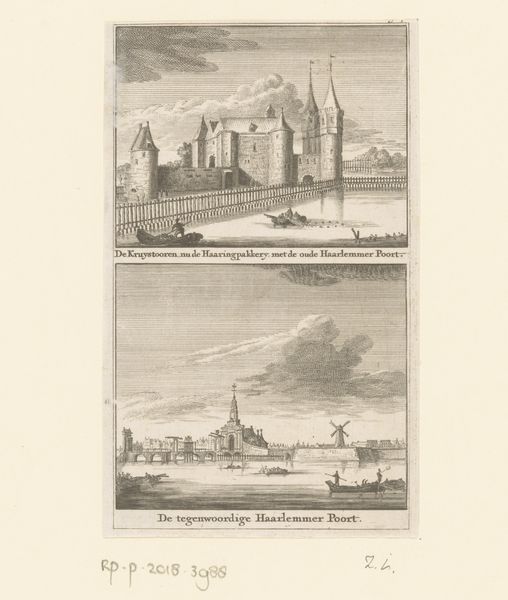

Gezigt van het dorp Slooten / Gezigt van de Sparwouder Poort, te Haarlem 1761 - 1804

0:00

0:00

ervendeweduwejacobusvanegmont

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 400 mm, width 325 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

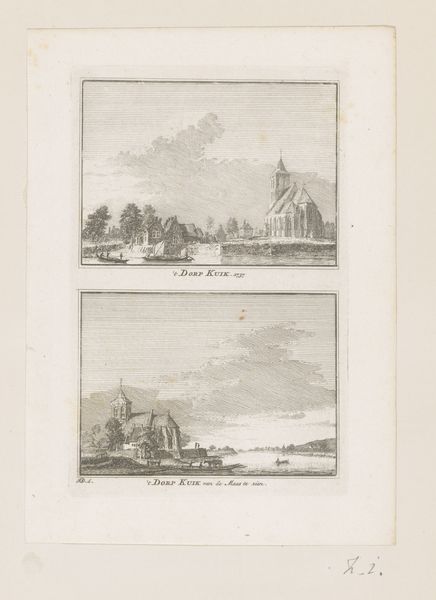

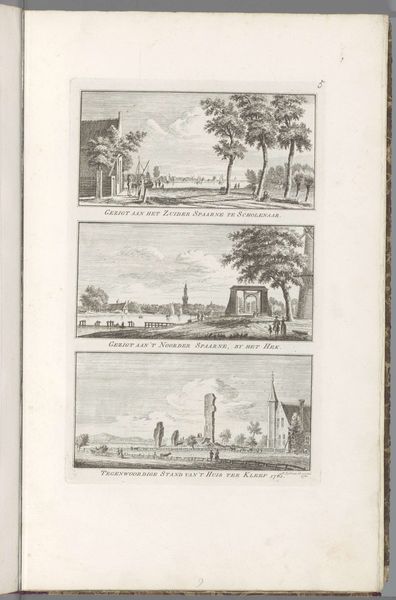

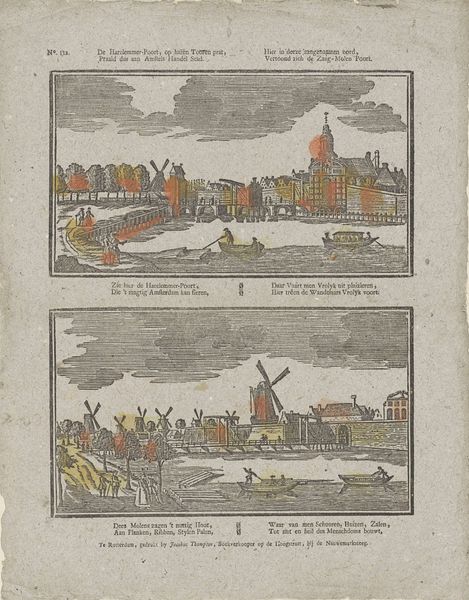

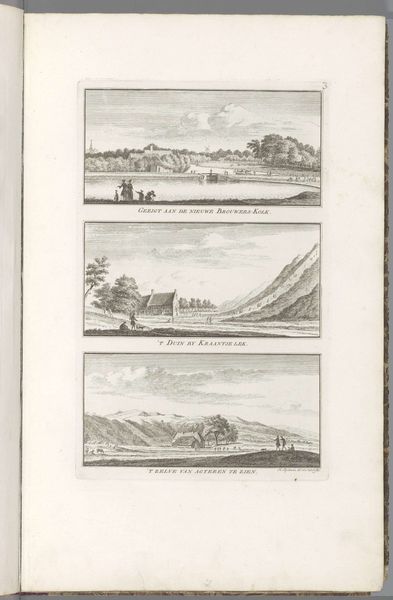

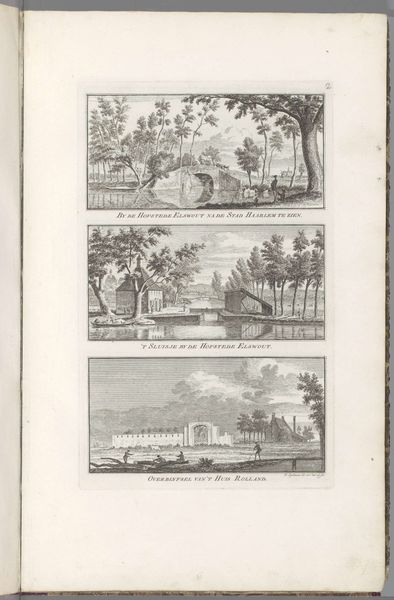

Curator: This double view engraving, "Gezigt van het dorp Slooten / Gezigt van de Sparwouder Poort, te Haarlem," dates sometime between 1761 and 1804, and it is currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It comes to us from Erven de Weduwe Jacobus van Egmont, published as a print, but it definitely echoes painting practices. What do you think? Editor: At first glance, there's a stark division; the world above feels orderly, a space of curated gentility, with hints of human interactions with animals, while the space below conveys the tensions between communal activities, boundaries, and exclusions. Curator: It is all about how it was made, an interesting choice to include two separate images. As an engraving, this artwork is reproducible and made to be shared widely, it would’ve circulated in multiple contexts. I would really be interested in looking at this specific print with a magnifying glass to examine its process. Editor: Absolutely! Let’s look beyond mere depictions of landscape, although genre-painting feels accurate; to me this double piece reveals something deeper about class and labor relations within Dutch society at the time. Notice how in the Sparwouder Poort image, the posture of each group differs greatly based on where they are positioned? Curator: And we see here both town and country! We get a picture of landscape under the growing tide of urbanization. Look, we can also discern evidence of the labor involved: someone had to etch those incredibly precise lines to depict figures, architecture, and the delicate textures of foliage. Editor: Precisely. And who had access to these images? Were they intended to inform, beautify, or perhaps subtly reinforce existing hierarchies? The division into top and bottom enforces a distinction, possibly a binary between the wealthy countryside with its animal labor, versus an area of greater working population. I find myself thinking of the social conditions from which it emerges, the economic currents, and power dynamics that shaped its creation and reception. Curator: Viewing it now, knowing its reproducible nature, encourages us to examine not only its aesthetic value but also its value as a form of communication and possibly even early mass media. It definitely makes me ponder who Jacobus van Egmont was, as well as who this “Widow of Jacobus van Egmont” was; the piece highlights production! Editor: A powerful perspective to keep in mind, for me. The piece isn't simply about visual charm, but also about the circulation of power through images—involving considerations of who is represented, for whom, and to what end. A pertinent insight for our present times.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.