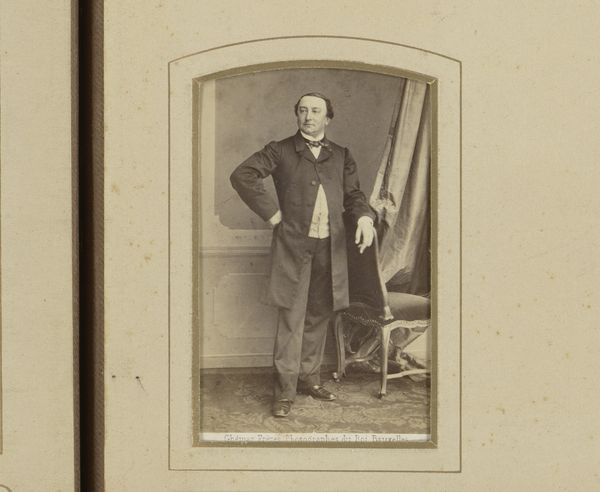

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

19th century

#

realism

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

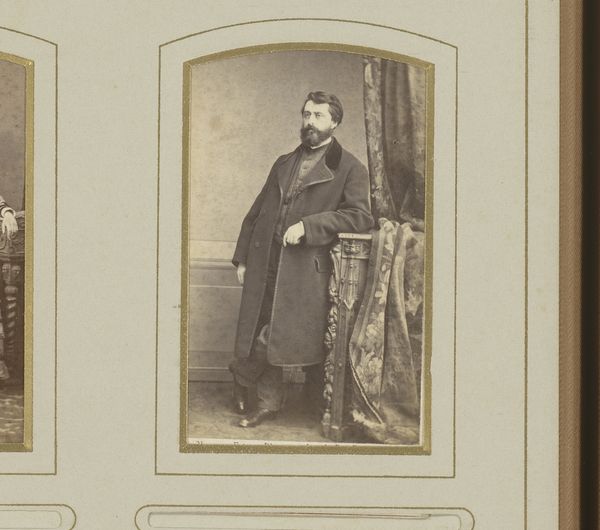

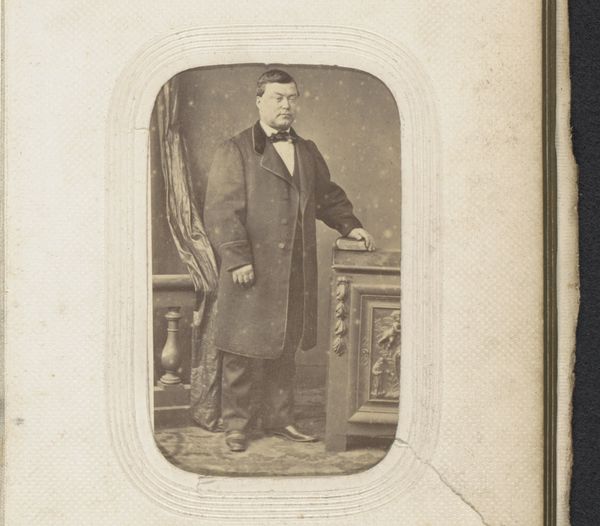

Curator: This dignified image, taken sometime between 1860 and 1894, is attributed to Ghémar Frères. The Rijksmuseum collection identifies it as "Portret van een staande man met hoed in de hand," or "Portrait of a standing man with a hat in his hand." Editor: There's a formality to the man's stance, the muted tones lending an almost melancholic feel. He exudes a quiet confidence. Curator: The photograph's albumen print gives it that distinctive sepia tone, characteristic of 19th-century photographic processes. It's fascinating to consider the materiality itself: the careful preparation of the glass plate, the light-sensitive emulsion… all crucial steps in capturing this moment. It really speaks to the craftsmanship involved. Editor: Indeed. And the hat he's holding so precisely—almost symbolically, don’t you think? Hats, particularly top hats like that, were a clear indicator of status, aspirations, and, most importantly, belonging to a certain social class at that period. The hat, and how it is handled, can be considered part of the symbolic message of self-representation that the man consciously wanted to project. Curator: I agree; but I see it more in terms of the socio-economic framework. The ability to commission a portrait, the garments the subject wears, speaks volumes about production, capital, and class. It suggests this man operated comfortably within a particular economic system. It reveals how power structures materialized. Editor: Possibly. The slight, almost concealed smirk hints a personal narrative beneath the composed facade, no? Consider how this portrait conforms to archetypes, the visual cues, and conventions that tell a story beyond the surface, allowing viewers to connect with something that outlasts historical periods. Curator: Again, good points; I can see those individual readings layered into our understanding. But without fully comprehending those underlying material processes and historical class structures, those interpretations become detached, superficial. I'd hate to romanticize a portrait without acknowledging that it only existed for this type of person, based on how photos and art were consumed at the time. Editor: Perhaps, but by contemplating visual archetypes that endure over generations, and not just class structures, we touch the eternal themes and meanings that speak across social classes, wouldn’t you say? Curator: Fair enough, I see your point. He looks pretty good with that top hat. Editor: As do you with your critical thinking hat.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.